**Section I. FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

****PART ONE. FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS IN FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

The following six chapters provide a gradual introduction to the foundations of financial analysis. They examine the concepts of cash flow, earnings, capital employed and invested capital, and look at the ways in which these concepts are linked.

They are fundamental for readers who have only a vague knowledge of the business world and basic accounting techniques. In this case, our advice is to read them and reread them before going further.

Chapter 2. CASH FLOW

Let’s work from A to Z (unless it turns out to be Z to A!)

Let’s begin our understanding of the business by analysing the cash flows that pre-exist any accounting or management system.

Section 2.1 CLASSIFYING COMPANY CASH FLOWS

Let’s consider, for example, the monthly account statement that individual customers receive from their bank. It is presented as a series of lines showing the various inflows and outflows of money on precise dates and the type of transaction (debit card payment or cash withdrawal, for instance).

Our first step is to trace the rationale for each of the entries on the statement, which could be everyday purchases, payment of a salary, automatic transfers, internet subscriptions, loan repayments or the receipt of bond interests, to mention a few examples.

The corresponding task for a financial manager is to reclassify company cash flows by category to draw up a cash flow document that can be used to:

- analyse past trends in cash flow (the document put together is generally known as a cash flow statement1); or

- project future trends in cash flow, over a shorter or longer period (the document needed is a cash flow budget or plan).

With this goal in mind, we will now demonstrate that cash flows can be classified into one of the following processes:

- Activities that form part of the industrial and commercial life of a company:

- operating cycle;

- investment cycle.

- Financing activities to fund these cycles:

- the debt cycle;

- the equity cycle.

Section 2.2 OPERATING AND INVESTMENT CYCLES

1/ THE IMPORTANCE OF THE OPERATING CYCLE

Let’s take the example of a greengrocer, Mr G, who is “cashing up” one evening. What does he find? First, he sees how much he spent in cash at the wholesale market in the morning and then the cash proceeds from fruit and vegetable sales during the day. If we assume that the greengrocer sold all the produce he bought in the morning at a mark-up, then the balance of receipts and payments for the day will be a cash surplus.

Unfortunately, things are usually more complicated in practice. It’s rare that all the goods bought in the morning are sold by the evening, especially in the case of a manufacturing business.

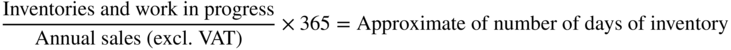

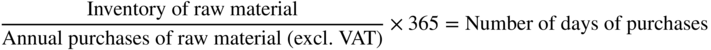

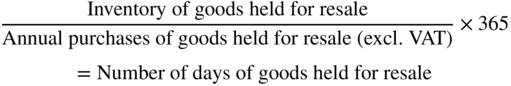

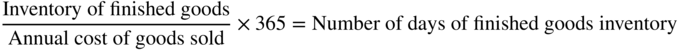

A company processes raw materials as part of an operating cycle, the length of which varies tremendously, from a day in the newspaper sector to seven years in the cognac sector. There is, then, a time lag between purchases of raw materials and the sale of the corresponding finished goods.

This time lag is not the only complicating factor. It is unusual for companies to buy and sell in cash. Usually, their suppliers grant them extended payment periods, and they can in turn grant their customers extended payment periods. The money received during the day does not necessarily come from sales made on the same day.

As a result of customer credit,2 supplier credit3 and the time it takes to manufacture and sell products or services, the operating cycle of each and every company spans a certain period, leading to timing differences between operating outflows and the corresponding operating inflows.

Each business has its own operating cycle of a certain length that, from a cash flow standpoint, may lead to positive or negative cash flows at different times. Operating outflows and inflows from different cycles are analysed by period, e.g. by month or by year. The balance of these flows is called operating cash flow. Operating cash flow reflects the cash flows generated by operations during a given period.

In concrete terms, operating cash flow represents the cash flow generated by the company’s operations. Returning to our initial example of an individual looking at his bank statement, it represents the difference between the receipts and normal outgoings, such as food, electricity and rent.

Naturally, unless there is a major timing difference caused by some unusual circumstances (start-up period of a business, very strong growth, very strong seasonal fluctuations), the balance of operating receipts and payments should be positive.

Readers with accounting knowledge will note that operating cash flow is independent of any accounting policies, which makes sense since it relates only to cash flows. More specifically:

- neither the company’s depreciation and provisioning policy,

- nor its inventory valuation method,

- nor the techniques used to defer costs over several periods have any impact on the figure.

However, the concept is affected by decisions about how to classify payments between investment and operating outlays, as we will now examine more closely.

2/ INVESTMENT AND OPERATING OUTFLOWS

Let’s return to the example of our greengrocer, who now decides to add frozen food to his business.

The operating cycle will no longer be the same. The greengrocer may, for instance, begin receiving deliveries once a week only and will therefore have to run much larger inventories. Admittedly, the impact of the longer operating cycle due to much larger inventories may be offset by larger credit from his suppliers. The key point here is to recognise that the operating cycle will change.

The operating cycle is different for each business and, generally speaking, the more sophisticated the end product, the longer the operating cycle.

But most importantly, before he can start up this new activity, our greengrocer needs to invest in a chest freezer.

What difference is there between this investment and operating outlays?

The outlay on the chest freezer seems to be a prerequisite. It forms the basis for a new activity, the success of which is unknown. It appears to carry higher risks and will be beneficial only if overall operating cash flow generated by the greengrocer increases. Lastly, investments are carried out from a long-term perspective and have a longer life than that of the operating cycle. Indeed, they last for several operating cycles, even if they do not last forever given the fast pace of technological progress.

This justifies the distinction, from a cash flow perspective, between operating and investment outflows.

Normal outflows, from an individual’s perspective, differ from an investment outflow in that they afford enjoyment, whereas investment represents abstinence. As we will see, this type of decision represents one of the vital underpinnings of finance. Only the very puritanically minded would take more pleasure from buying a microwave than from spending the same amount of money at a restaurant! Only one of these choices can be an investment and the other an ordinary outflow. So, what purpose do investments serve? Investment is worthwhile only if the decision to forego normal spending, which gives instant pleasure, will subsequently lead to greater gratification.

This is the definition of the return on investment (be it industrial or financial) from a cash flow standpoint. We will use this definition throughout this book.

The impact of investment outlays is spread over several operating cycles. Financially, capital expenditures are worthwhile only if inflows generated thanks to these expenditures exceed the outflows by an amount yielding at least the return on investment expected by the investor.

Note also that a company may sell some assets in which it has invested in the past. For instance, our greengrocer may decide after several years to trade in his freezer for a larger model. The proceeds would also be part of the investment cycle.

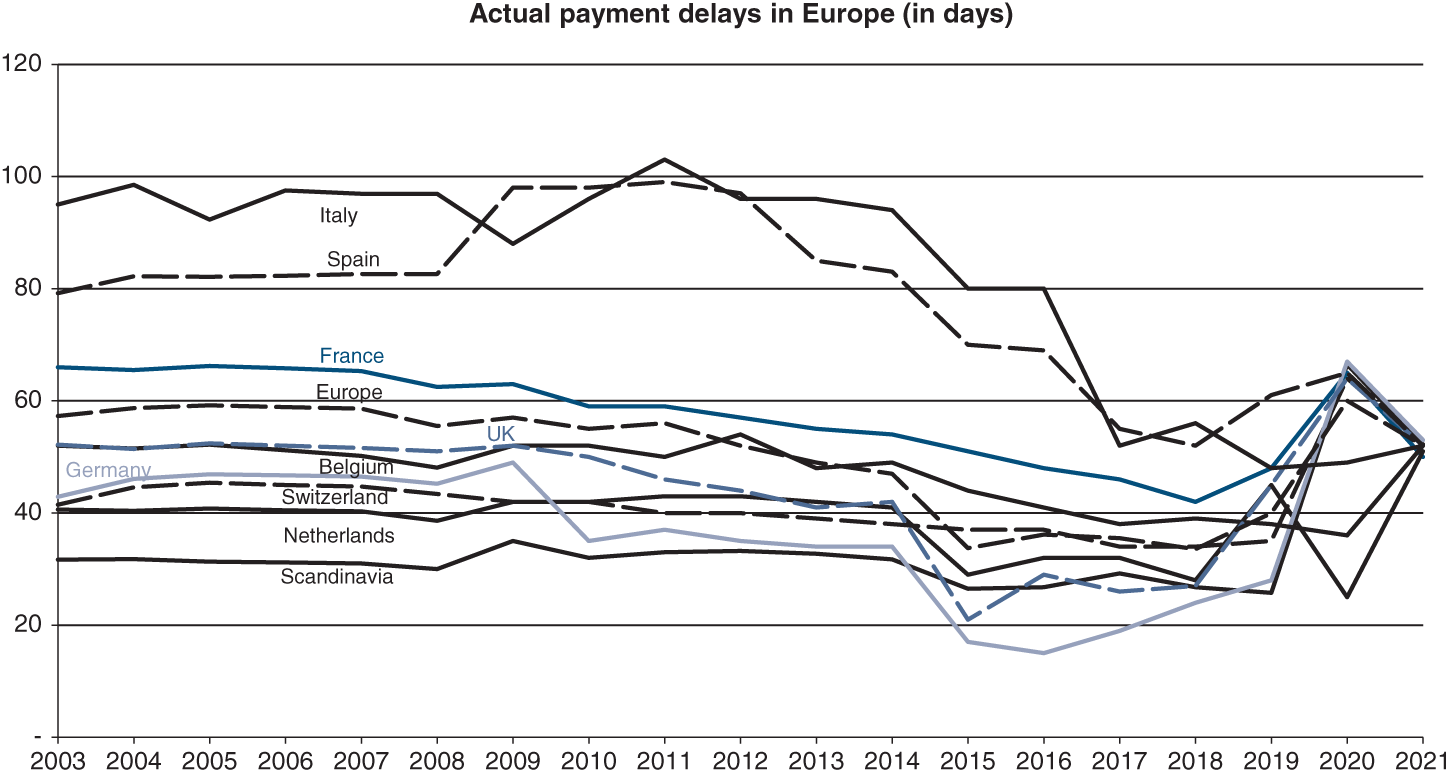

3/ FREE CASH FLOW

Before-tax free cash flow is defined as the difference between operating cash flow and capital expenditure net of fixed asset disposals.

As we shall see in Sections II and III of this book, free cash flow can be calculated before or after tax. It also forms the basis for the most important valuation technique. Operating cash flow is a concept that depends on how expenditure is classified between operating and investment outlays. Since this distinction is not always clear-cut, operating cash flow is not widely used in practice, with free cash flow being far more popular. If free cash flow turns negative, then additional financial resources will have to be raised to cover the company’s cash flow requirements.

Section 2.3 FINANCIAL RESOURCES

The operating and investment cycles give rise to a timing difference in cash flows. Employees and suppliers have to be paid before customers settle up. Likewise, investments have to be completed before they generate any receipts. Naturally, this cash flow deficit needs to be filled. This is the role of financial resources.

The purpose of financial resources is simple: they must cover the shortfalls resulting from these timing differences by providing the company with sufficient funds to balance its cash flow.

These financial resources are provided by investors: shareholders, debtholders, lenders, etc. These financial resources are not provided with “no strings attached”. In return for providing the funds, investors expect to be subsequently rewarded by receiving dividends or interest payments, registering capital gains, etc. This can happen only if the operating and investment cycles generate positive cash flows.

To the extent that the financial investors have made the investment and operating activities possible, they expect to receive, in various different forms, their fair share of the surplus cash flows generated by these cycles.

At its most basic, the principle would be to finance these treasury shortfalls solely using capital that incurs the risk of the business. Such capital is known as shareholders’ equity. This type of financial resource forms the cornerstone of the entire financial system. Its importance is such that shareholders providing it are granted decision-making powers and control over the business in various different ways. From a cash flow standpoint, the equity cycle comprises inflows from capital increases and outflows in the form of dividend payments to the shareholders.

Like individuals, a business may decide to ask lenders rather than shareholders to help it cover a cash flow shortage. Bankers will lend funds only after they have carefully analysed the company’s financial health. They want to be nearly certain of being repaid and do not want exposure to the company’s business risk. These cash flow shortages may be short term or long term, but lenders do not want to take on business risk. The capital they provide represents the company’s debt capital.

The debt cycle is the following: the business arranges borrowings in return for a commitment to repay the capital and make interest payments regardless of trends in its operating and investment cycles. These undertakings represent firm commitments, ensuring that the lender is certain of recovering its funds provided that the commitments are met. Debt can finance:

- the investment cycle, with the increase in future net receipts set to cover capital repayments and interest payments on borrowings; and

- the operating cycle, with credit making it possible to bring forward certain inflows or to defer certain outflows.

From a cash flow standpoint, the life of a business comprises an operating and an investment cycle, leading to a positive or negative free cash flow. If free cash flow is negative, then the financing cycle covers the funding shortfall. But free cash flow cannot be forever negative: sooner or later investors must get a return and/or get repaid, and they can only get a return and/or get repaid by a positive free cash flow.

The risk incurred by the lender is that this commitment will not be met. Theoretically speaking, debt may be regarded as an advance on future cash flows generated by the investments made and guaranteed by the company’s shareholders’ equity.

Although a business needs to raise funds to finance investments, it may also find, at a given point in time, that it has a cash surplus, i.e. the funds available exceed cash requirements.

These investments are generally realised with a view to ensuring the possibility of a very quick exit without any risk of losses.

Although at first sight short-term financial investments (marketable securities) may be regarded as investments since they generate a rate of return, we advise readers to consider them instead as the opposite of debt. As we will see, company treasurers often have to raise additional debt even if at the same time the company holds short-term investments without speculating in any way.

Debt and short-term financial investments or marketable securities should not be considered independently of each other, but as inextricably linked. We suggest that readers reason in terms of debt net of short-term financial investments and financial expense net of financial income.

Putting all the individual pieces together, we arrive at the following simplified cash flow statement, with the balance reflecting the net decrease in the company’s debt during a given period:

SIMPLIFIED CASH FLOW STATEMENT

| n – 2 | n – 1 | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating receipts − Operating payments | |||

| = Operating cash flow | |||

| − Capital expenditure + Fixed asset disposals | |||

| = Free cash flow before tax | |||

| − Financial expense net of financial income − Corporate income tax + Proceeds from share issue − Dividends paid | |||

| = Net decrease in debt | |||

| With: Repayments of borrowings − New bank and other borrowings + Change in marketable securities + Change in cash and cash equivalents | |||

| = Net decrease in debt |

This short chapter is seminal and the reader who is discovering the notions it contains for the first time should not hesitate to read it twice in order to grasp them fully.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

Chapter 3. EARNINGS

Time to put our accounting hat on!

Following our analysis of company cash flows, it is time to consider the issue of how a company creates wealth. In this chapter, we are going to study the income statement to show how the various cycles of a company create wealth.

Section 3.1 ADDITIONS TO WEALTH AND DEDUCTIONS FROM WEALTH

What would your spontaneous answer be to the following questions?

- Does purchasing an apartment make you richer or poorer?

- Would your answer change if you were to buy the apartment on credit?

There can be no doubt as to the correct answer. Provided that you pay the market price for the apartment, your wealth is not affected whether or not you buy it on credit. Our experience as teachers has shown us that students often confuse cash and wealth.

Consequently, we advise readers to train their minds by analysing the impact of all transactions in terms of cash flows and wealth impacts.

For instance, when you buy an apartment, you become neither richer nor poorer, but your cash decreases. Arranging a loan makes you no richer or poorer than you were before (you owe the money), but your cash has increased. If a fire destroys your house and it was not insured, you are worse off, but your cash position has not changed, since you have not spent any money.

Raising debt is tantamount to increasing your financial resources and commitments at the same time. As a result, it has no impact on your net worth. Buying an apartment for cash results in a change in the nature of your assets (reduction in cash, increase in real estate assets), without any change in net worth. The possible examples are endless. Spending money does not necessarily make you poorer. Likewise, receiving money does not necessarily make you richer.

The job of listing all the items that positively or negatively affect a company’s wealth is performed by the income statement,1 which shows all the additions to wealth (revenues) and all the deductions from wealth (charges or expenses or costs). The fundamental aim of all businesses is to increase wealth. Additions to wealth cannot be achieved without some deductions from wealth. In sum, earnings represent the difference between additions to and deductions from wealth.

Since the rationale behind the income statement is not the same as for a cash flow statement, some cash flows do not appear on the income statement (those that neither generate nor destroy wealth). Likewise, some revenues and costs are not shown on the cash flow statement (because they have no impact on the company’s cash position).

1/ EARNINGS AND THE OPERATING CYCLE

The operating cycle forms the basis of the company’s wealth. It consists of both:

- additions to wealth (products and services sold, i.e. products and services whose worth is recognised in the market); and

- deductions from wealth (consumption of raw materials or goods for resale, use of labour, use of external services such as transportation, taxes and other duties).

The very essence of a business is to increase wealth by means of its operating cycle.

It may be described as gross insofar as it covers just the operating cycle and is calculated before non-cash expenses such as depreciation and amortisation, and before interest and taxes.

2/ EARNINGS AND THE INVESTING CYCLE

(a) Principles

Investing activities do not appear directly on the income statement. In a wealth-oriented approach, an investment represents a use of funds that retains some value.

That said, the value of investments may change over time:

(b) Accounting for a decrease in the value of fixed assets

The decrease in value of a fixed asset due to its use by the company is accounted for by means of depreciation and amortisation.3

Impairment losses or write-downs on fixed assets recognise the loss in value of an asset not related to its day-to-day use, i.e. the unforeseen diminution in the value of:

- an intangible asset (goodwill, patents, etc.);

- a tangible asset (property, plant and equipment);

- an investment in a subsidiary.

3/ THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN OPERATING COSTS AND FIXED ASSETS

Although we are easily able to define investment from a cash flow perspective, we recognise that our approach goes against the grain of the traditional presentation of these matters, especially as far as those familiar with accounting are concerned:

- Whatever is consumed as part of the operating cycle to create something new belongs to the operating cycle. Without wishing to philosophise, we note that the act of creation always entails some form of destruction.

- Whatever is used without being destroyed directly, thus retaining its value, belongs to the investment cycle. This represents an immutable asset or, in accounting terms, a fixed asset (a “non-current asset” in IFRS terminology).

For instance, to make bread, a baker uses flour, salt, yeast and water, all of which form part of the end product. The process also entails labour, which has a value only insofar as it transforms the raw material into the end product. At the same time, the baker also needs a bread oven, which is absolutely essential for the production process, but is not destroyed by it. Though this oven may experience wear and tear, it will be used many times over.

This is the major distinction that can be drawn between operating costs and fixed assets. It may look deceptively straightforward, but in practice is no clearer than the distinction between investment and operating outlays. For instance, does an advertising campaign represent a charge linked solely to one period with no impact on any other? Or does it represent the creation of an asset (a brand)?

4/ THE COMPANY’S OPERATING PROFIT

From EBITDA, which is linked to the operating cycle, we deduct non-cash costs, which comprise depreciation and amortisation and impairment losses or write-downs on fixed assets.

This gives us operating income or operating profit or EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes), which reflects the increase in wealth generated by the company’s industrial and commercial activities.

The term “operating” contrasts with the term “financial”, reflecting the distinction between the real world and the realms of finance. Indeed, operating income is the product of the company’s industrial and commercial activities before its financing operations are taken into account. Operating profit or EBIT may also be called operating income, trading profit or operating result.

5/ EARNINGS AND THE FINANCING CYCLE

(a) Debt capital

Repayments of borrowings do not constitute costs but, as their name suggests, merely repayments.

Just as common sense tells us that securing a loan does not increase wealth, neither does repaying a borrowing represent a charge.

We emphasise this point because our experience tells us that many mistakes are made in this area.

Conversely, we should note that the interest payments made on borrowings lead to a decrease in the wealth of the company and thus represent an expense for the company. As a result, they are shown on the income statement.

Similarly, when a company invests cash in financial products (money market funds, interest-bearing accounts), the interest received is recognised as financial income. The difference between financial income and financial expense is called net financial expense/(income).

The difference between operating profit and net financial expense is called profit before tax and non-recurring items.4

(b) Shareholders’ equity

From a cash flow standpoint, shareholders’ equity is formed through issuance of shares minus outflows in the form of dividends or share buy-backs. These cash inflows give rise to ownership rights over the company. The income statement measures the creation of wealth by the company; it therefore naturally ends with the net earnings (also called net profit). Whether the net earnings are paid in dividends or not is a simple choice of cash position made by the shareholder.

If we take a step back, we see that net earnings and financial interest are based on the same principle of distributing the wealth created by the company. Likewise, income tax represents earnings paid to the state in spite of the fact that it does not contribute any funds to the company.

6/ RECURRENT AND NON-RECURRENT ITEMS: EXTRAORDINARY AND EXCEPTIONAL ITEMS, DISCONTINUED OPERATIONS

We have now considered all the operations of a business that may be allocated to the operating, investing and financing cycles of a company. That said, it is not hard to imagine the difficulties involved in classifying the financial consequences of certain extraordinary events, such as losses incurred as a result of earthquakes, other natural disasters or the expropriation of assets by a government.

They are not expected to occur frequently or regularly and are beyond the control of a company’s management – hence, the idea of creating a separate catch-all category for precisely such extraordinary items.

We will see in Chapter 9 that the distinction between non-recurring and recurring items is a difficult and subjective distinction, all the more so as accounting standards do little to help us.

Among the many different types of exceptional events, we will briefly focus on asset disposals. Investing forms an integral part of the industrial and commercial activities of businesses. But the best-laid plans may fail, while others may lead down a strategic impasse.

Put another way, disinvesting is also a key part of an entrepreneur’s activities. It generates exceptional “asset disposal” inflows on the cash flow statement and capital gains and losses on the income statement, which may appear under exceptional items or not. It is for the analyst to decide whether these gains and losses are recurring, and thus part of the operations; or not, and then constitute non-recurring items. More generally, some non-recurring items have a cash impact, some have none (goodwill depreciation, for example).

By definition, it is easier to analyse and forecast profit before tax and non-recurrent items than net income or net profit, which is calculated after the impact of non-recurrent items and tax.

7/ NET INCOME

Net income measures the creation or destruction of wealth during the fiscal year. Net income is a wealth indicator, not a cash indicator. It incorporates wealth-destructive items like depreciation, which are non-cash items, and most of the time it does not show increases in value, which are only recorded when they are realised through asset sales.

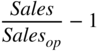

Section 3.2 DIFFERENT INCOME STATEMENT FORMATS

Two main formats of income statement are frequently used, which differ in the way they present revenues and expenses related to the operating and investment cycles. They may be presented either:

- by function,5 i.e. according to the way revenues and costs are used in the operating and investing cycle. This shows the cost of goods sold, selling and marketing costs, research and development costs and general and administrative costs; or

- by nature,6 i.e. by type of expenditure or revenue, which shows the change in inventories of finished goods and in work in progress (closing minus opening inventory), purchases of and changes in inventories of goods for resale and raw materials (closing minus opening inventory), other external costs, personnel expenses, taxes and other duties, depreciation and amortisation.

| Presentation | China | France | Germany | India | Italy | Japan | Morocco | Russia | Switzerland | UK | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By nature | 0% | 23% | 30% | 100% | 66% | 10% | 100% | 21% | 27% | 10% | 0% | |

| By function | 92% | 53% | 67% | 0% | 27% | 90% | 0% | 75% | 66% | 90% | 60% | |

| Other | 8% | 23% | 3% | 0% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 4% | 7% | 0% | 40% |

Source: 2020 annual reports from the top 30 listed non-financial groups in each country

The by-nature presentation predominates to a great extent in Italy, India and Morocco. In the US, the by-function presentation is largely predominant.7

Whereas in the past, France, Germany and Switzerland tended to use systematically the by-nature or by-function format, the current situation is less clear-cut. Moreover, a new presentation is making some headway; it is mainly a by-function format but depreciation and amortisation are not included in the cost of goods sold, in selling and marketing costs or research and development costs, but are isolated on a separate line.

The two different income statement formats can be summarised by the following diagram:

1/ THE BY-FUNCTION INCOME STATEMENT FORMAT

This presentation is based on a management accounting approach, in which costs are allocated to the main corporate functions:

| Function | Corresponding cost |

|---|---|

| Production | Cost of sales, or cost of goods sold |

| Commercial | Selling and marketing costs |

| Research and development | Research and development costs |

| Administration | General and administrative costs |

As a result, personnel expense is allocated to each of these four categories (or three where selling, general and administrative costs are pooled into a single category), depending on whether an individual employee works in production, sales, research or administration. Likewise, depreciation expense for a tangible fixed asset is accounted for under cost of goods sold if it relates to production machinery, to selling and marketing costs if it concerns a car used by the sales team, to research and development costs if it relates to laboratory equipment, or to general and administrative costs in the case of the accounting department’s computers, for example.

The underlying principle is very simple indeed. This format clearly shows that operating profit is the difference between sales and the cost of sales irrespective of their nature (i.e. production, sales, research and development, administration).

On the other hand, it does not differentiate between the operating and investment processes, since depreciation and amortisation is not shown directly on the income statement (it is split up between the four main corporate functions), obliging analysts to track down the information in the cash flow statement or in the notes to the accounts.

2/ THE BY-NATURE INCOME STATEMENT FORMAT

The by-nature format is simple to apply, even for small companies, because no allocation of expenses is required. It offers a more detailed breakdown of costs.

Naturally, as in the previous approach, operating profit is still the difference between sales and the cost of sales.

In this format, costs are recognised as they are incurred rather than when the corresponding items are used. Showing on the income statement all purchases made and all invoices sent to customers during the same period would not be comparing like with like.

A business may transfer to inventory some of the purchases made during a given year. The transfer of these purchases to inventory does not destroy any wealth. Instead, it represents the formation of an asset, albeit probably a temporary one, but one that has real value at a given point in time. Secondly, some of the end products produced by the company may not be sold during the year and yet the corresponding costs appear on the income statement.

To compare like with like, it is necessary to:

- eliminate changes in inventories of raw materials and goods for resale from purchases to get raw materials and goods for resale that were used rather than simply purchased;

- add changes in the inventory of finished products and work in progress back to sales. As a result, the income statement shows production rather than just sales.

The by-nature format shows the amount spent on production for the period and not the total expenses under the accruals convention. It has the logical disadvantage that it seems to imply that changes in inventory are a revenue or an expense in their own right, which they are not. They are only an adjustment to purchases to obtain relevant costs.

Exercise 1 will help readers get to grips with the concept of changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress.

To sum up, there are two different income statement formats:

- the by-nature format, which is focused on production, in which all the costs incurred during a given period are recorded. This amount then needs to be adjusted (for changes in inventories) so that it may be compared with products sold during the period;

- the by-function format, which is built directly in terms of the cost price of goods or services sold.

Either way, it is worth noting that EBITDA depends heavily on the inventory valuation methods used by the business. This emphasises the appeal of the by-nature format, which shows inventory changes on a separate line of the income statement and thus clearly indicates their order of magnitude.

Like operating cash flow, EBITDA is not influenced by the valuation methods applied to tangible and intangible fixed assets or the taxation system.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 Also called a Profit and Loss statement or P&L account.

- 2 But IFRS have created some exceptions to this principle that we will see in Chapters 6 and 7.

- 3 Amortisation is sometimes used instead of depreciation, particularly in the context of intangible assets.

- 4 Or non-recurrent items.

- 5 Also called by-destination income statement.

- 6 Also called by-category income statement.

- 7 The US airline companies are an exception as most of them use the by-nature income statement.

Chapter 4. CAPITAL EMPLOYED AND INVESTED CAPITAL

The end-of-period snapshot

So far in our analysis, we have looked at inflows and outflows, or revenues and costs during a given period. We will now temporarily set aside this dynamic approach and place ourselves at the end of the period (rather than considering changes over a given period) and analyse the balances outstanding.

For instance, in addition to changes in net debt over a period, we also need to analyse net debt at a given point in time. Likewise, we will study here the wealth that has been accumulated up to a given point in time, rather than that generated over a period.

The balance represents a snapshot of the cumulative inflows and outflows previously generated by the business.

To summarise, we can make the following connections:

- an inflow or outflow represents a change in “stock”, i.e. in the balance outstanding;

- a “stock” is the sum of inflows and outflows since a given date (when the business started up) through to a given point in time. For instance, at any moment, shareholders’ equity is equal to the sum of capital increases (net of capital decreases) by shareholders and annual net income for past years not distributed in the form of dividends plus the original share capital.

Section 4.1 THE BALANCE SHEET: DEFINITIONS AND CONCEPTS

The purpose of a balance sheet is to list all the assets of a business and all of its financial resources at a given point in time.

1/ MAIN ITEMS ON A BALANCE SHEET

Assets on the balance sheet comprise:

- fixed assets,1 i.e. everything required for the operating cycle that is not destroyed as part of it. These items retain some value (any loss in their value is accounted for through depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses). A distinction is drawn between tangible fixed assets (land, buildings, machinery, etc.),2intangible fixed assets (brands, patents, software, goodwill, etc.) and investments. When a business holds shares in another company (in the long term), they are accounted for under investments;

- inventories and trade receivables, i.e. temporary assets created as part of the operating cycle;

- lastly, marketable securities and cash that belong to the company and are thus assets.

Inventories, receivables,3 marketable securities and cash represent the current assets, a term reflecting the fact that these assets tend to “turn over” during the operating cycle.

Resources on the balance sheet comprise:

- capital provided by shareholders, plus retained earnings, known as shareholders’ equity;

- borrowings of any kind that the business may have arranged, e.g. bank loans, supplier credits, etc., known as liabilities.

THE BALANCE SHEET

| SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY | |

| FIXED ASSETS | |

| (or NON-CURRENT ASSETS) | |

| LIABILITIES | |

| CURRENT ASSETS |

By definition, a company’s assets and resources must be exactly equal. This is the fundamental principle of double-entry accounting. When an item is purchased, it is either capitalised or expensed. If it is capitalised, it will appear on the asset side of the balance sheet, and if expensed, it will lead to a reduction in earnings and thus shareholders’ equity. The double-entry for this purchase is either a reduction in cash (i.e. a decrease in an asset) or a commitment (i.e. a liability) to the vendor (i.e. an increase in a liability). According to the algebra of accounting, assets and resources (equity and liabilities) always carry the opposite sign, so the equilibrium of the balance sheet is always maintained.

It is European practice to classify assets starting with fixed assets and to end with cash,4 whereas it is North American and Japanese practice to start with cash. The same is true for the equity and liabilities side of the balance sheet: Europeans start with equity, whereas North Americans and Japanese end with it.

A “horizontal” format is common in continental Europe, with assets on the left and resources on the right. In the UK, the more common format is a “vertical” one, starting from fixed assets plus current assets and deducting liabilities to end up with equity. These are only choices of presentation.

2/ TWO WAYS OF ANALYSING THE BALANCE SHEET

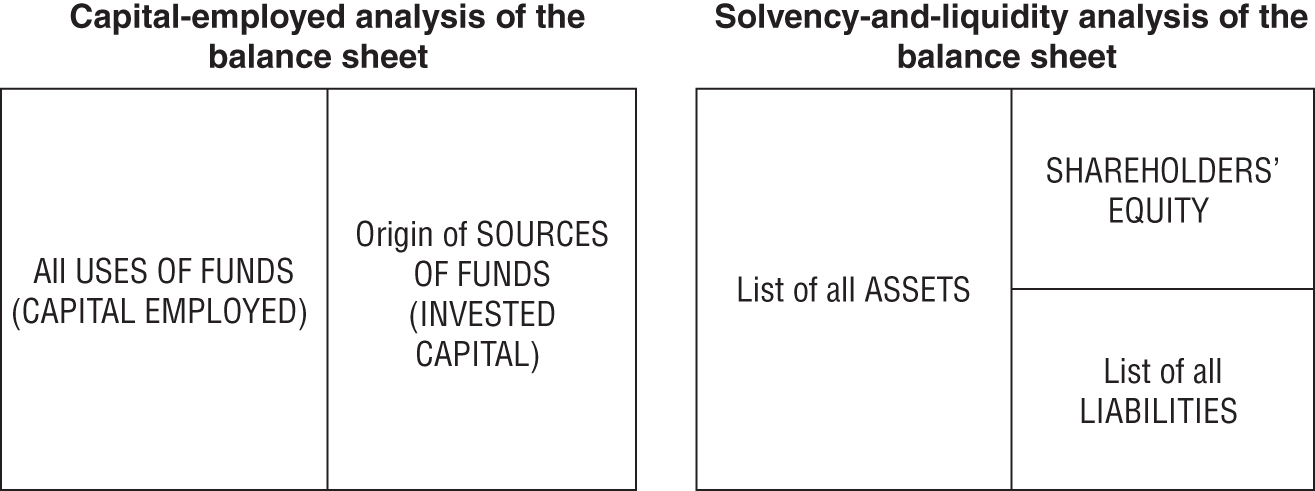

A balance sheet can be analysed either from a capital-employed perspective or from a solvency-and-liquidity perspective.

In the capital-employed analysis, the balance sheet shows all the uses of funds for the company’s operating cycle and analyses the origin of its sources of funds.

A capital-employed analysis of the balance sheet serves three main purposes:

- to illustrate how a company finances its operating assets (see Chapter 12);

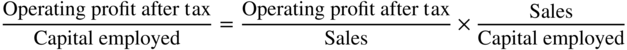

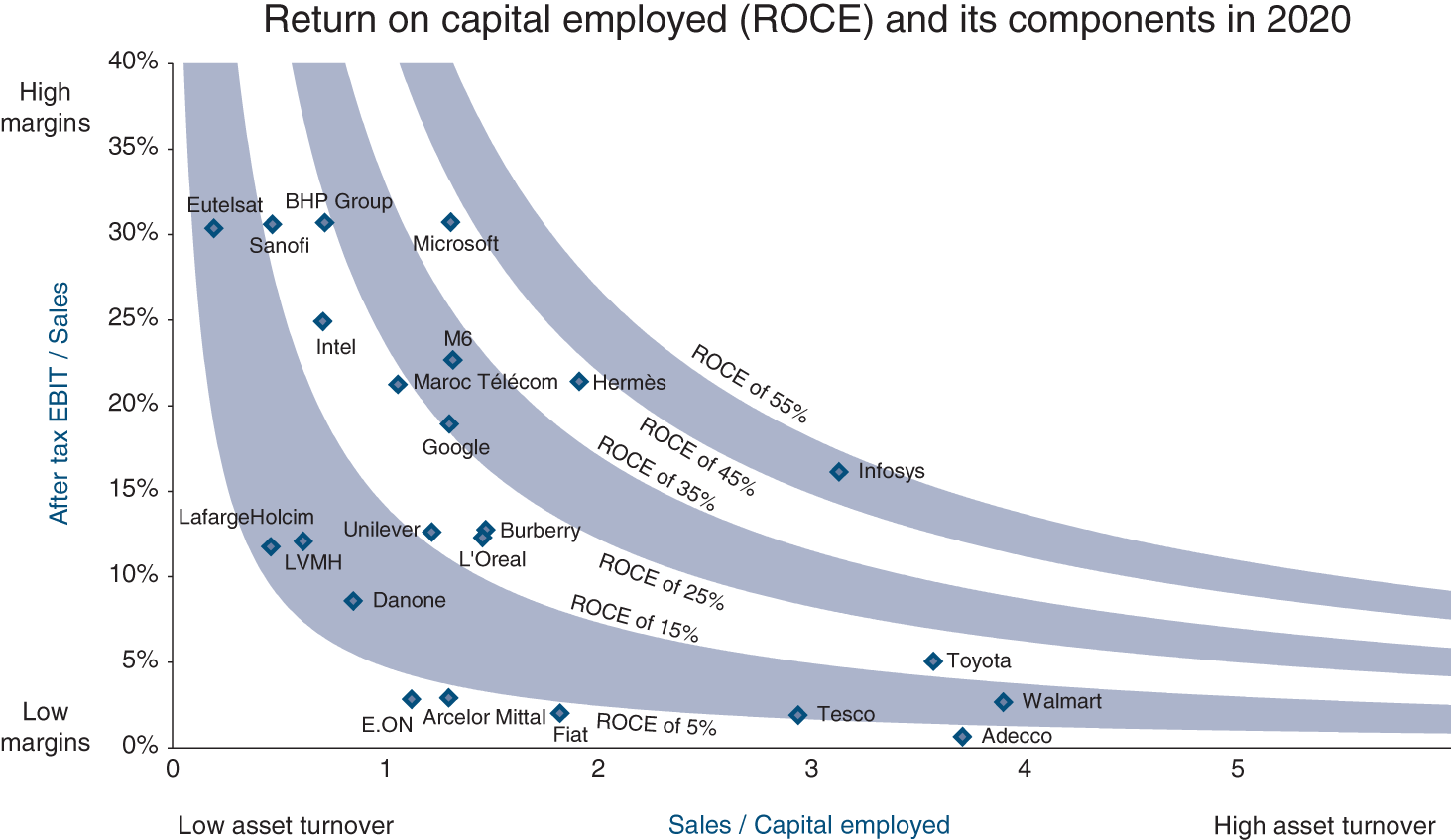

- to compute the rate of return either on capital employed or on equity (see Chapter 13); and

- as a first step to valuing the equity of a company as a going concern (see Chapter 31).

In a solvency-and-liquidity analysis, a business is regarded as a set of assets and liabilities, the difference between them representing the book value of the equity provided by shareholders. From this perspective, the balance sheet lists everything that a company owns and everything that it owes.

A solvency-and-liquidity analysis of the balance sheet serves three purposes:

- to measure the solvency of a company (see Chapter 14);

- to measure the liquidity of a company (see Chapter 12); and

- as a first step to valuing its equity in a bankruptcy scenario.

Section 4.2 A CAPITAL-EMPLOYED ANALYSIS OF THE BALANCE SHEET

To gain a firm understanding of the capital-employed analysis of the balance sheet, we believe it is best approached in the same way as the analysis in the previous chapter, except that here we will be considering “stocks” rather than inflows and outflows.

More specifically, in a capital-employed analysis, a balance sheet is divided into the following main headings.

1/ FIXED ASSETS, ALSO CALLED NON-CURRENT ASSETS

These represent all the investments carried out by the business, based on our financial and accounting definition. In IFRS and US GAAP it would also include operating lease right of use assets.

It is helpful to distinguish wherever possible between operating assets and non-operating assets that have nothing to do with the company’s business activities, e.g. land, buildings and subsidiaries active in significantly different or non-core businesses. Non-operating assets can thus be excluded from the company’s capital employed. By isolating non-operating assets, we can assess the resources the company may be able to call upon in hard times (i.e. through the disposal of non-operating assets).

The difference between operating and non-operating assets can be subtle in certain circumstances. For instance, how should a company’s head office on Bond Street or on the Champs-Elysées be classified? Probably under operating assets for a fashion house or a car manufacturer, but under non-operating assets for an engineering or construction group which has no business reason to be on Bond Street (unlike Burberry).

2/ OPERATING WORKING CAPITAL

Operating working capital is the difference between uses of funds and sources of funds linked to the daily operations of a company.

Uses of funds comprise all the operating costs incurred but not yet used or sold (i.e. inventories) and all sales that have not yet been paid for (trade receivables).

Sources of funds comprise all charges incurred but not yet paid for (trade payables, social security and tax payables), as well as operating revenues from products that have not yet been delivered (advance payments on orders).

The net balance of operating uses and sources of funds is called the working capital.

If uses of funds exceed sources of funds, the balance is positive and working capital needs to be financed. This is the most frequent case. If negative, it represents a source of funds generated by the operating cycle. This is a nice – but rare – situation!

It is described as “working capital” because the figure reflects the cash required to cover financing shortfalls arising from day-to-day operations.

Sometimes working capital is defined as current assets minus current liabilities. This definition corresponds to our working capital definition + marketable securities and net cash – short-term financial and banking borrowings. We think that this is an improper definition of working capital as it mixes items from the operating cycle (inventories, receivables, payables) and items from the financing cycle (marketable securities, net cash and short-term bank and financial borrowings). You may also find in some documents expressions such as “working capital needs” or “requirements in working capital”. These are synonyms for working capital.

Operating working capital comprises the following accounting entries:

Only the normal amount of operating sources of funds is included in calculations of operating working capital. Unusually long payment periods granted by suppliers should not be included as a component of normal operating working capital.

Where it is permanent, the abnormal portion should be treated as a source of cash, with the suppliers thus being considered as playing the role of the company’s banker.

Inventories of raw materials and goods for resale should be included only at their normal amount. Under no circumstances should an unusually large figure for inventories of raw materials and goods for resale be included in the calculation of operating working capital.

Where appropriate, the excess portion of inventories or the amount considered as inventory held for speculative purposes can be treated as a high-risk short-term investment.

Working capital is totally independent of the methods used to value fixed assets, depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets. However, it is influenced by:

- inventory valuation methods;

- deferred income and cost over one or more years (accruals);

- the company’s provisioning policy for current assets and operating liabilities and costs.

As we shall see in Chapter 5, working capital represents a key principle of financial analysis.

3/ NON-OPERATING WORKING CAPITAL

Although we have considered the timing differences between inflows and outflows that arise during the operating cycle, we have, until now, always assumed that capital expenditures are paid for when purchased and that non-recurring costs are paid for when they are recognised in the income statement. Naturally, there may be timing differences here, giving rise to what is known as non-operating working capital.

Non-operating working capital, which is not a very robust concept from a theoretical perspective, is hard to predict and to analyse because it depends on individual transactions, unlike operating working capital, which is recurring.

In practice, non-operating working capital is a catch-all category for items that cannot be classified anywhere else. It includes amounts due on fixed assets, extraordinary items, etc.

4/ CAPITAL EMPLOYED

Capital employed is the sum of a company’s fixed assets and its working capital (i.e. operating and non-operating working capital). It is therefore equal to the sum of the net amounts devoted by a business to both the operating and investing cycles. It is also known as operating assets.

Capital employed is financed by two main types of funds: shareholders’ equity and net debt, sometimes grouped together under the heading of invested capital.

5/ FINANCIAL RESOURCES OR INVESTED CAPITAL

Capital employed is financed by two financial resources: shareholders’ equity and net debt.

Shareholders’ equity comprises capital provided by shareholders when the company is initially formed and at subsequent capital increases, as well as capital left at the company’s disposal in the form of earnings transferred to the reserves.

The company’s gross debt comprises debt financing, irrespective of its maturity, i.e. medium- and long-term (various borrowings due in more than one year that have not yet been repaid), and short-term bank or financial borrowings (portion of long-term borrowings due in less than one year, discounted notes, bank overdrafts, etc.) to which IFRS and US GAAP add operating lease liabilities. A company’s net debt goes further by deducting cash and equivalents (e.g. petty cash and bank accounts) and marketable securities, which are the opposite of debt (the company lending money to banks or financial markets), that could be used to partially or totally reduce the gross debt. It is also called net financial position.

Net debt, or net financial position, can thus be calculated as follows:

A company’s net debt can be either positive or negative. If it is negative, the company is said to have net cash.

In the previous paragraphs, we looked at the key accounting items, but some are a bit more complex to allocate (pensions, accruals, etc.) and we will develop these in Chapter 7.

From a capital-employed standpoint, a company balance sheet can be analysed as follows, with the example of the ArcelorMittal group, the world steel leader. This balance sheet will be used in future chapters.

BALANCE SHEET FOR ARCELORMITTAL

| in $m | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goodwill | 5,651 | 5,737 | 5,728 | 5,432 | 4,312 | |

| + | Other intangible fixed assets | 49 | – | – | – | – |

| + | Tangible fixed assets | 34,782 | 36,971 | 35,638 | 35,104 | 29,807 |

| + | Equity in associated companies | 4,297 | 5,084 | 4,906 | 6,529 | 6,817 |

| + | Other non-current assets | 2,538 | 3,884 | 6,326 | 2,420 | 4,462 |

| = | NON-CURRENT ASSETS (FIXED ASSETS) | 47,317 | 51,676 | 52,598 | 49,485 | 45,398 |

| Inventories | 14,734 | 17,986 | 20,744 | 17,296 | 12,328 | |

| + | Trade receivables | 7,682 | 8,888 | 9,412 | 8,005 | 6,872 |

| + | Other operating receivables | 1,665 | 1,931 | 2,834 | 2,756 | 2,281 |

| − | Trade payables | 11,633 | 13,428 | 13,981 | 12,614 | 11,525 |

| − | Other operating payables | 4,597 | 5,197 | 6,307 | 5,804 | 5,596 |

| = | OPERATING WORKING CAPITAL (1) | 7,851 | 10,180 | 12,702 | 9,639 | 4,360 |

| Non-operating receivables | 4,329 | |||||

| − | Non-operating payables | 2,087 | 2,575 | 5,014 | 4,993 | 5,884 |

| = | NON-OPERATING WORKING CAPITAL (2) | (2,087) | (2,575) | (5,014) | (4,993) | (1,555) |

| = | WORKING CAPITAL (1+2) | 5,764 | 7,605 | 7,688 | 4,646 | 2,805 |

| CAPITAL EMPLOYED = NON-CURRENT ASSETS + WORKING CAPITAL | 53,081 | 59,281 | 60,286 | 54,131 | 48,203 | |

| = | SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY GROUP SHARE | 30,135 | 38,790 | 42,086 | 38,521 | 38,280 |

| + | Minority interests in consolidated subsidiaries | 2,190 | 2,066 | 2,022 | 1,962 | 1,957 |

| – | Deferred tax assets | 5,837 | 7,055 | 8,287 | 8,680 | 7,866 |

| + | Deferred tax liabilities | 2,529 | 2,684 | 2,374 | 2,331 | 1,832 |

| = | TOTAL GROUP EQUITY | 29,017 | 36,485 | 38,195 | 34,134 | 34,203 |

| Medium- and long-term borrowings and liabilities | 11,789 | 10,143 | 9,316 | 10,344 | 9,000 | |

| + | Bank overdrafts and short-term borrowings | 6,593 | 7,809 | 8,147 | 7,305 | 6,307 |

| − | Cash and equivalents, marketable securities | 2,615 | 2,786 | 2,354 | 4,995 | 5,963 |

| + | Pensions liabilities | 8,297 | 7,630 | 6,982 | 7,343 | 4,656 |

| = | NET DEBT | 24,064 | 22,796 | 22,091 | 19,997 | 14,000 |

| INVESTED CAPITAL = (GROUP EQUITY + NET DEBT) = CAPITAL EMPLOYED | 53,081 | 59,281 | 60,286 | 54,131 | 48,203 |

Items specific to consolidated accounts are highlighted in blue and will be described in detail in Chapter 6.

Section 4.3 A SOLVENCY-AND-LIQUIDITY ANALYSIS OF THE BALANCE SHEET

The solvency-and-liquidity analysis of the balance sheet, which presents a statement of what is owned and what is owed by the company at the end of the year, can be used:

- by shareholders to list everything that the company owns and owes, bearing in mind that these amounts may need to be revalued;

- by creditors looking to assess the risk associated with loans granted to the company. In a capitalist system, shareholders’ equity is the ultimate guarantee in the event of liquidation since the claims of creditors are met before those of shareholders.

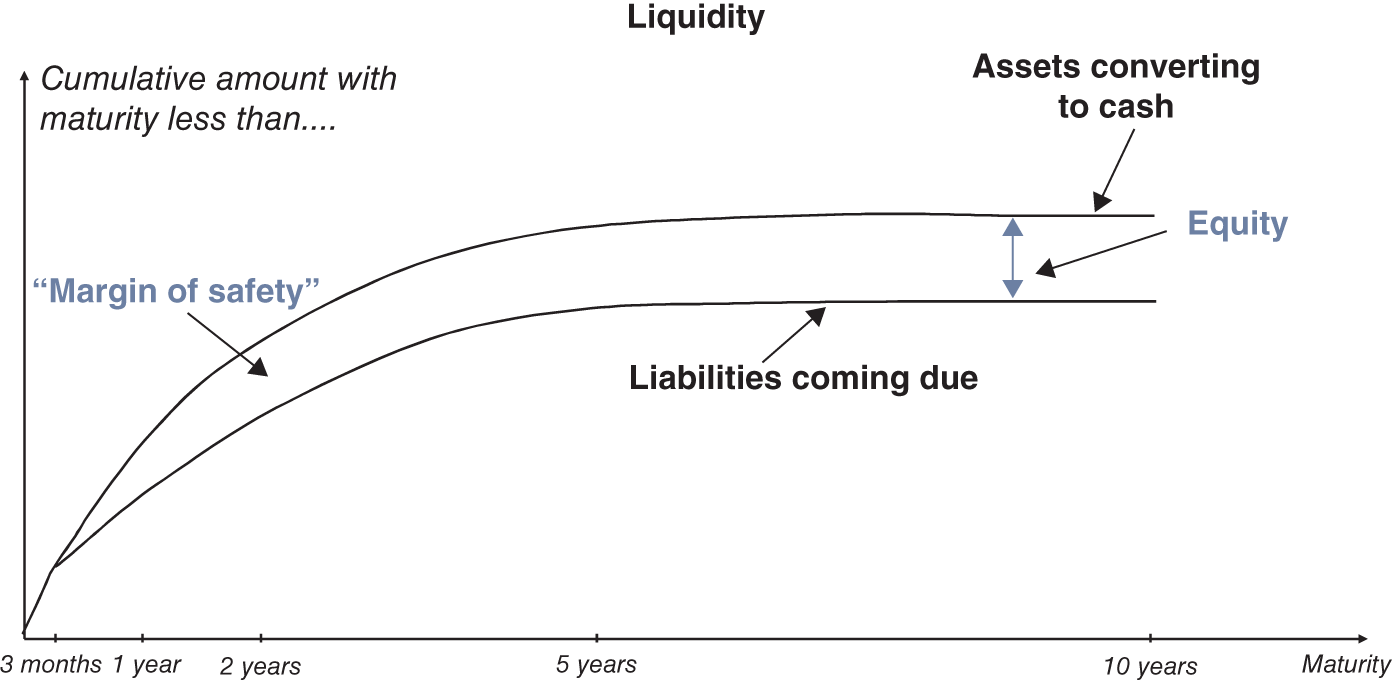

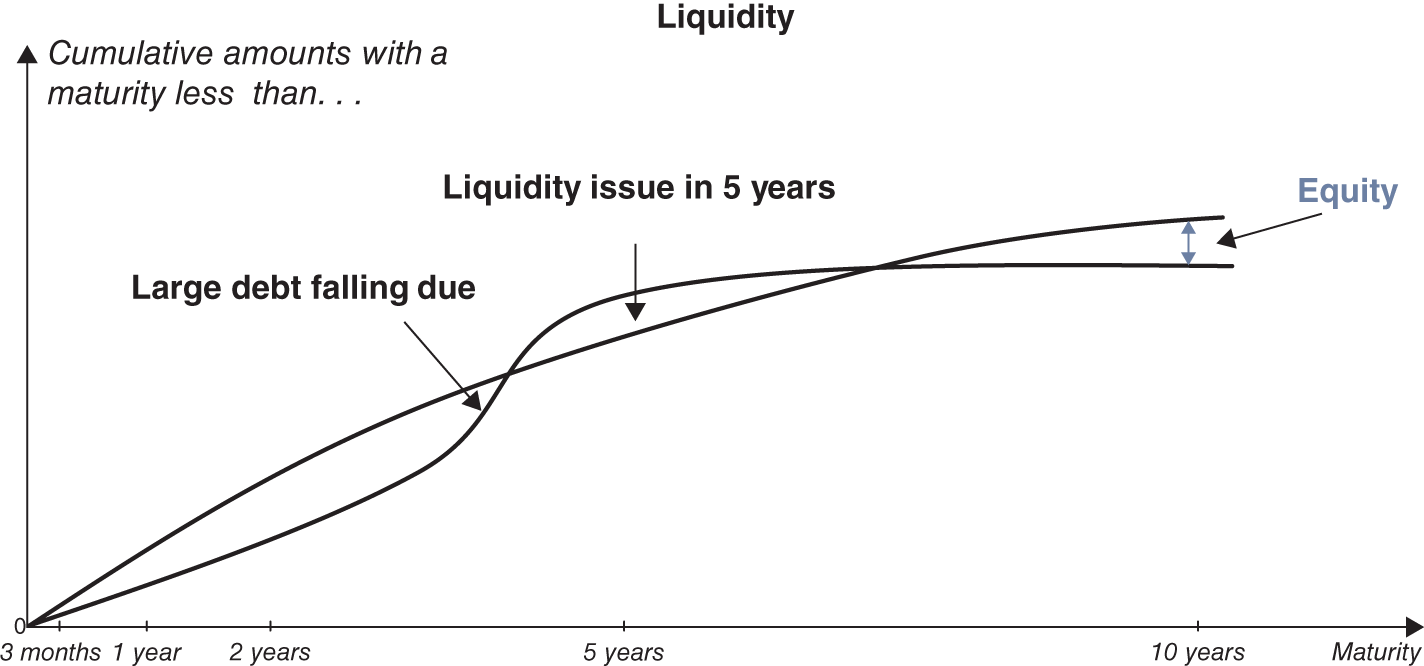

Hence the importance attached to a solvency-and-liquidity analysis of the balance sheet in traditional financial analysis. As we shall see in detail in Chapters 12 and 14, it may be analysed from either a liquidity or a solvency perspective.

1/ BALANCE SHEET LIQUIDITY

A classification of the balance sheet items needs to be carried out prior to the liquidity analysis. Liabilities are classified in the order in which they fall due for repayment. Since balance sheets are published annually, a distinction between the short term and the long term turns on whether a liability is due in less than or more than one year. Accordingly, liabilities are classified into those due in the short term (less than one year), in the medium and long term (more than one year) and those that are not due for repayment.

Likewise, what the company owns can also be classified by duration as follows:

- assets that will have disappeared from the balance sheet by the following year, which comprise current assets in the vast majority of cases;

- assets that will still appear on the balance sheet the following year, which comprise fixed assets in the vast majority of cases.

From a liquidity perspective, we classify liabilities by their due date, investments by their maturity date and assets as follows:

Accordingly, they comprise (unless the operating cycle is unusually long) inventories and trade receivables.

Balance sheet liquidity therefore derives from the fact that the turnover of assets (i.e. the speed at which they are monetised within the operating cycle) is faster than the turnover of liabilities (i.e. when they fall due). The maturity schedule of liabilities is known in advance because it is defined contractually. However, the liquidity of current assets is unpredictable (risk of sales flops or inventory write-downs, etc.). Consequently, the clearly defined maturity structure of a company’s liabilities contrasts with the unpredictable liquidity of its assets.

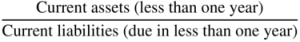

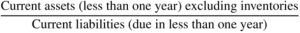

Therefore, short-term creditors will take into account differences between a company’s asset liquidity and its liability structure. They will require the company to maintain current assets at a level exceeding that of short-term liabilities to provide a margin of safety. Hence the sacrosanct rule in finance that each and every company must have assets due to be monetised in less than one year at least equal to its liabilities falling due within one year.

2/ SOLVENCY

In accounting terms, a company may be regarded as insolvent once its shareholders’ equity turns negative. This means that it owes more than it owns.

Sometimes, the word solvency is used in a broader sense, meaning the ability of a company to repay its debts as they become due (see Chapter 12).

3/ NET ASSET VALUE OR THE BOOK VALUE OF SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY

This is a solvency-oriented concept that attempts to compute the funds invested by shareholders by valuing the company as the difference between its assets and its liabilities. Net asset value is an accounting and, in some instances, tax-related term, rather than a financial one.

The book value of shareholders’ equity is equal to everything a company owns less everything it already owes or may owe. Financiers often talk about net asset value, which leads to confusion among non-specialists, who can construe them as total assets net of depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses.

Book value of equity is thus equal to the sum of:

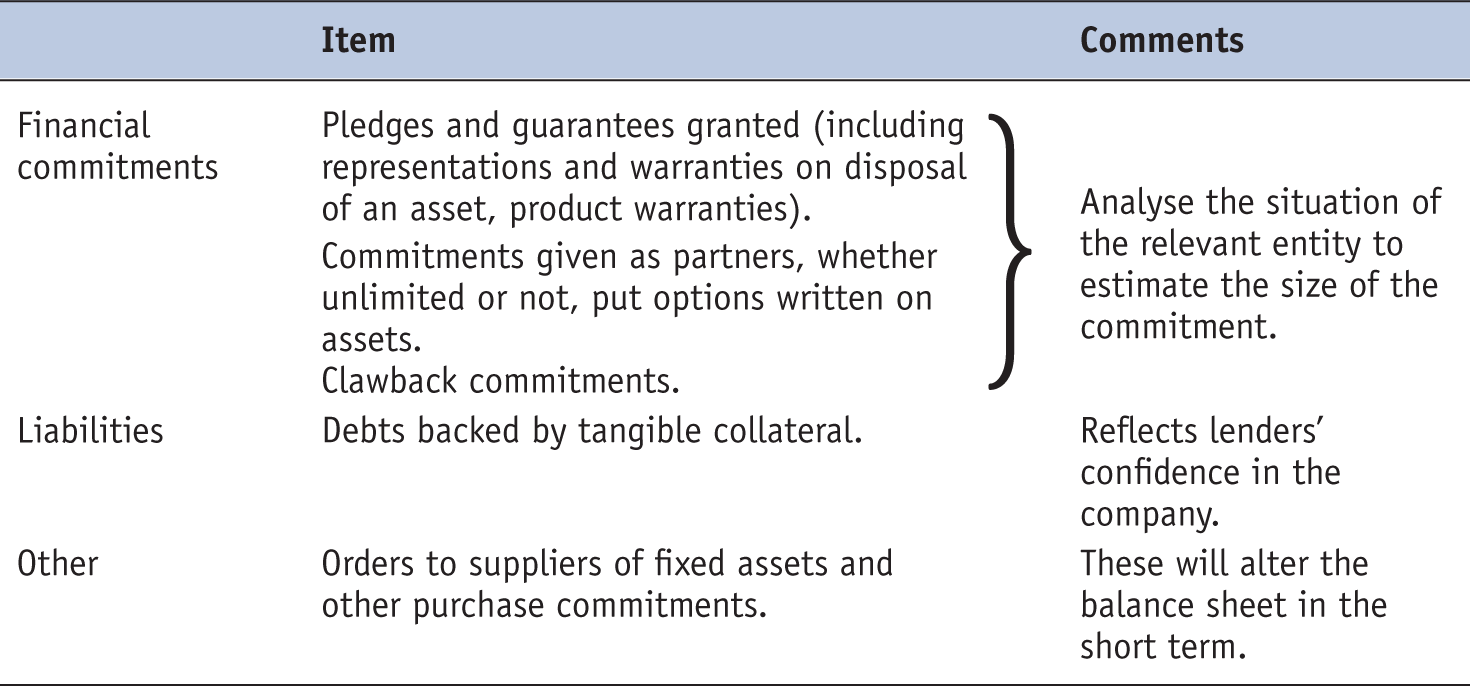

When a company is sold, the buyer will be keen to adopt an even stricter approach:

- by factoring in contingent liabilities (that do not appear on the balance sheet);

- by excluding worthless assets, i.e. of zero value. This very often applies to some intangible assets (see Chapter 7).

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISE

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

Chapter 5. WALKING THROUGH FROM EARNINGS TO CASH FLOW

Or how to move mountains together!

Chapter 2 showed the structure of the cash flow statement, which brings together all the receipts and payments recorded during a given period and determines the change in net debt position.

Chapter 3 covered the structure of the income statement, which summarises all the revenues and charges during a period.

It may appear that these two radically different approaches have nothing in common. But common sense tells us that a rich woman will sooner or later have cash in her pocket, while a poor woman is likely to be strapped for cash – unless she should make her fortune along the way.

Although the complex workings of a business lead to differences between profits and cash, they converge at some point or another.

First of all, we will examine revenues and costs from a cash flow standpoint. Based on this analysis, we will establish a link between changes in wealth (earnings) and the change in net debt that bridges the two approaches.

We recommend that readers get to grips with this chapter, because understanding the transition from earnings to the change in net debt represents a key step in comprehending the financial workings of a business.

Section 5.1 ANALYSIS OF EARNINGS FROM A CASH FLOW PERSPECTIVE

This section is included merely for explanatory and conceptual purposes. Even so, it is vital to understand the basic financial workings of a company.

1/ OPERATING REVENUES

Operating receipts should correspond to sales for the same period, but they differ because:

- customers may be granted a payment period; and/or

- payments of invoices from the previous period may be received during the current period.

As a result, operating receipts are equal to sales only if sales are immediately paid in cash. Otherwise, they generate a change in trade receivables.

| − | Increase in trade receivables | |||

| Sales for the period | or | = | Operating receipts | |

| + | Reduction in trade receivables |

2/ CHANGES IN INVENTORIES OF FINISHED GOODS AND WORK IN PROGRESS

As we have already seen in by-nature income statements, the difference between production and sales is adjusted for through changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress.1 But this is merely an accounting entry, to deduct from operating costs those costs that do not correspond to products sold. It has no impact from a cash standpoint.2 As a result, changes in inventories need to be reversed in a cash flow analysis.

3/ OPERATING COSTS

Operating costs differ from operating payments in the same way as operating revenues differ from operating receipts. Operating payments are the same as operating costs for a given period only when adjusted for:

- timing differences arising from the company’s payment terms (credit granted by its suppliers, etc.);

- the fact that some purchases are not used during the same period. The difference between purchases made and purchases used is adjusted for through change in inventories of raw materials.

These timing differences give rise to:

- changes in trade payables in the first case;

- discrepancies between raw materials used and purchases made, which are equal to change in inventories of raw materials and goods for resale.

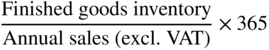

The total amount of the timing differences between operating revenues and costs and between operating receipts and payments can thus be summarised as follows for by-nature and by-function income statements:

| BY-NATURE INCOME STATEMENT | DIFFERENCE | CASH FLOW STATEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Net sales | − Change in trade receivables (deferred payment) | = Operating receipts |

| + Changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress | − Changes in inventories of finished goods and work in progress (deferred charges) | |

| − Operating costs except depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses | − Change in trade payables (deferred payments) | = − Operating payments |

| − Change in inventories of raw materials and goods for resale (deferred charges) | ||

| = | = | = |

| = EBITDA | − Change in operating working capital | = Operating cash flows |

| BY-FUNCTION INCOME STATEMENT | DIFFERENCE | CASH FLOW STATEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Net sales | − Change in trade receivables (deferred payment) + Change in trade payables (deferred payments) | = Operating receipts |

| − Operating costs except depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses | − Change in inventories of finished goods, work in progress, raw materials and goods for resale (deferred changes) | = − Operating payments |

| = EBITDA | − Change in operating working capital | = Operating cash flows |

Astute readers will have noticed that the items in the central column of the above table are the components of the change in operating working capital between two periods, as defined in Chapter 4.

Over a given period, the change in operating working capital represents a need for, or a source of, financing.

If positive, it represents a financing requirement and we refer to an increase in operating working capital. If negative, it represents a source of funds and we refer to a reduction in operating working capital.

The change in working capital merely represents a straightforward timing difference between the balance of operating cash flows (operating cash flow) and the wealth created by the operating cycle (EBITDA). As we shall see, it is important to remember that timing differences may not necessarily be small, of limited importance, short or negligible in any way.

4/ CAPITAL EXPENDITURE

Capital expenditures3 lead to a change in what the company owns without any immediate increase or decrease in its wealth. Consequently, they are not shown directly on the income statement. Conversely, capital expenditures have a direct impact on the cash flow statement.

A company’s capital expenditure process leads to both cash outflows that do not diminish its wealth at all and the accounting recognition of impairment in the purchased assets through depreciation and amortisation that does not reflect any cash outflows.

Accordingly, there is no direct link between cash flow and net income for the capital expenditure process, as we knew already.

5/ FINANCING

Financing is, by its very nature, a cycle that is specific to inflows and outflows. Sources of financing (new borrowings, capital increases, etc.) do not appear on the income statement, which shows only the remuneration paid on some of these resources, i.e. interest on borrowings but not dividends on equity.

Outflows representing a return on sources of financing may be analysed as either costs (i.e. interest) or a distribution of wealth created by the company among its equity capital providers (i.e. dividends).

To keep things simple, assuming that there are no timing differences between the recognition of a cost and the corresponding cash outflow, a distinction needs to be drawn between:

- interest payments on debt financing (financial expense) and income tax, which affect the company’s cash position and its earnings;

- the payments made to equity capital providers (dividends), which affects the company’s cash position and earnings transferred to reserves;

- new borrowings and repayment of borrowings, capital increases and share buy-backs,4 which affect its cash position, but have no impact on earnings.

Lastly, corporate income tax represents a charge that appears on the income statement and a cash payment to the state which, though it may not provide any financing to the company, provides it with a range of free services and entitlements, e.g. police, education, roads, etc. Corporate income tax is not always paid as soon as it becomes a cost, thus creating another time lag between a cost and its payment (similar to a variation in working capital).

We can now finish off our table and walk through from earnings to decrease in net debt:

FROM THE INCOME STATEMENT… TO THE CASH FLOW STATEMENT

| INCOME STATEMENT | DIFFERENCE | CASH FLOW STATEMENT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBITDA | − | Change in operating working capital | = | − | Operating cash flow | |

| − | Capital expenditure | = | − | Capital expenditure | ||

| + | Disposals | = | + | Disposals | ||

| − | Depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets | + | Depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets (non-cash charges) | |||

| = | EBIT (operating profit) | = | Free cash flow before tax | |||

| − | Financial expense net of financial income | − | Financial expense net of financial income | |||

| − | Corporate income tax | − | = | − | Corporate income tax | |

| + | Proceeds from share issues | = | + | Proceeds from share issues | ||

| – | Share buy-backs | – | Share buy-backs | |||

| – | Dividends paid | = | – | Dividends paid | ||

| = | Net income (net earnings) | + | Column total | = | Decrease in net debt |

Section 5.2 CASH FLOW STATEMENT

The same table enables us to move in the opposite direction and thus account for the decrease in net debt based on the income statement. To do so, we simply need to add back all the movements shown in the central column to net profit.

The following reasoning may help our attempt to classify the various line items that enable us to make the transition from net income to decrease in net debt.

Net income should normally turn up in “cash at hand”. That said, we also need to add back certain non-cash costs (depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets) that were deducted on the way down the income statement but have no cash impact, to arrive at what is known as cash flow.

Cash flow will appear in “cash at hand” only once the timing differences related to the operating cycle as measured by change in operating working capital have been taken into account.

Lastly, the investing and financing cycles give rise to uses and sources of funds that have no immediate impact on net income.

1/ FROM NET INCOME TO CASH FLOW

As we have just seen, depreciation, amortisation, impairment losses on fixed assets and provisions are non-cash costs that have no impact on a company’s cash position. From a cash flow standpoint, they are no different from net income.

These two items form the company’s cash flow, which accountants allocate between net income on the one hand and depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on the other hand, according to the relevant accounting and tax legislation.

The simplicity of the cash flow statement shown in Chapter 2 was probably evident to our readers, but it would not fail to shock traditional accountants, who would find it hard to accept that financial expense should be placed on a par with repayments of borrowings. Raising debt to pay financial expense is not the same as replacing one debt with another. The former makes the company poorer, whereas the latter constitutes liability management.

As a result, traditionalists have managed to establish the concept of cash flow. We need to point out that we would advise computing cash flow before any capital gains (or losses) on asset disposals and before non-recurring items, simply because they are non-recurrent items. Cash flow is only relevant in a cash flow statement if it is not made artificially volatile by inclusion of non-recurring items.

Cash flow is not as pure a concept as EBITDA. That said, a direct link may be established between these two concepts by deriving cash flow from the income statement using the top-down method:

or the bottom-up method:

* So as not to take them into account in the computation of cash flow as they are already included in net income.

Cash flow is influenced by the same accounting policies as EBITDA. Likewise, it is not affected by the accounting policies applied to tangible and intangible fixed assets.

Note that the calculation method differs slightly for consolidated accounts,5 since the contribution to consolidated net profit made by equity-accounted income is replaced by the dividend payment received. This is attributable to the fact that the parent company does not actually receive the earnings of an associate company since it does not control it, but merely receives a dividend.

Furthermore, cash flow is calculated at group level without taking into account minority interests. This seems logical, since the parent company has control of and allocates the cash flows of its fully-consolidated subsidiaries even if they are not fully owned. In the cash flow statement, minority interests in the controlled subsidiaries are reflected only through the dividend payments that they receive.

Lastly, readers should beware of cash flow as there are nearly as many definitions of cash flow as there are companies in the world!

The preceding definition is widely used, but frequently free cash flows, cash flow from operating activities and operating cash flow are simply called “cash flow” by some professionals. So, it is safest to check which cash flow they are talking about.

2/ FROM CASH FLOW TO CASH FLOW FROM OPERATING ACTIVITIES

In Chapter 2 we introduced the concept of cash flow from operating activities, which is not the same as cash flow.

To go from cash flow to cash flow from operating activities, we need to adjust for the timing differences in cash flows linked to the operating cycle.

This gives us the following equation:

Note that the term “operating activities” is used here in a fairly broad sense, since it includes financial expense and corporate income tax.

3/ OTHER MOVEMENTS IN CASH

We have now isolated the movements in cash deriving from the operating cycle, so we can proceed to allocate the other movements to the investment and financing cycles.

The investment cycle includes:

- capital expenditures (acquisitions of tangible and intangible assets);

- disposals of fixed assets, i.e. the price at which fixed assets are sold and not any capital gains or losses (which do not represent cash flows);

- changes in long-term investments (i.e. financial assets).

Where appropriate, we may also factor in the impact of timing differences in cash flows generated by this cycle, notably non-operating working capital (e.g. amount owed to a supplier of a fixed asset).

The financing cycle includes:

- capital increases in cash, the payment of dividends (i.e. payment out of the previous year’s net profit) and share buy-backs;

- change in net debt resulting from the repayment of (short-, medium- and long-term) borrowings, new borrowings, changes in marketable securities (short-term investments) and changes in cash and equivalents.

This brings us back to the cash flow statement in Chapter 2, but using the indirect method, which starts with net income and classifies cash flows by cycle (i.e. operating, investing or financing activities; see next page).

In practice, most companies publish a cash flow statement that starts with net income and moves down to changes in “cash and equivalents” or change in “cash”, a poorly defined concept since certain companies include marketable securities while others deduct bank overdrafts and short-term borrowings.

Net debt reflects the level of indebtedness of a company much better than cash and cash equivalents or than cash and cash equivalents minus short-term borrowings, since the latter are only a portion of the debt position of a company. On the one hand, one can infer relevant conclusions from changes in the net debt position of a company. On the other hand, changes in cash and cash equivalents are rarely relevant as it is so easy to increase cash on the balance sheet at the closing date: simply get into long-term debt and put the proceeds in a bank account! Cash on the balance sheet has increased but net debt is still the same.

CASH FLOW STATEMENT FOR ARCELORMITTAL ($M)

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPERATING ACTIVITIES | ||||||

| Net income | 1,734 | 4,575 | 5,330 | (2,391) | (578) | |

| + | Depreciation, amortisation and impairment losses on fixed assets | 2,721 | 2,768 | 2,799 | 2,969 | 2,894 |

| + | Other non-cash items | 50 | (1,263) | (3,173) | 2,720 | (132) |

| = | CASH FLOW | 4,505 | 6,080 | 4,956 | 3,298 | 2,184 |

| − | Change in working capital | 1,000 | 1,841 | 83 | (3,042) | (1,841) |

| = | CASH FLOW FROM OPERATING ACTIVITIES (A) | 3,505 | 4,239 | 4,873 | 6,340 | 4,025 |

| INVESTING ACTIVITIES | ||||||

| Capital expenditure | 2,444 | 2,819 | 3,305 | 3,772 | 2,578 | |

| − | Disposal of fixed assets | 119 | 22 | 26 | 468 | 237 |

| + | Acquisition of financial assets | – | 77 | 744 | 838 | – |

| − | Disposal of financial assets | 1,182 | 44 | 301 | 318 | 3,017 |

| = | CASH FLOW FROM INVESTING ACTIVITIES (B) | (1,143) | (2,830) | (3,722) | (3,824) | 676 |

| = | FREE CASH FLOW AFTER FINANCIAL EXPENSE (A – B) | 2,362 | 1,409 | 1,151 | 2,516 | 4,701 |

| FINANCING ACTIVITIES | ||||||

| Proceeds from share issues (C) | 3,115 | – | (226) | (90) | 1,477 | |

| Dividends paid (D) | 61 | 141 | 220 | 332 | 181 | |

| A − B + C − D = DECREASE/(INCREASE) IN NET DEBT | 5,416 | 1,268 | 705 | 2,094 | 5,997 | |

| Decrease in net debt can be broken down as follows: | ||||||

| Repayment of short-, medium- and long-term borrowings | 8,429 | 4,363 | 3,669 | 5,110 | 5,782 | |

| − | New short-, medium- and long-term borrowings | 1,526 | 3,266 | 2,532 | 5,657 | 753 |

| + | Change in cash, cash equivalents and marketable securities (short-term investments) | (1,487) | 171 | (432) | 2,641 | 968 |

| = | DECREASE/(INCREASE) IN NET DEBT | 5,416 | 1,268 | 705 | 2,094 | 5,997 |

However, it is easy to deduct the change in cash available and cash equivalents from the change in indebtedness:

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A − B + C − D = DECREASE/(INCREASE) IN NET DEBT | 5,416 | 1,268 | 705 | 2,094 | 5,997 | |

| – | Repayment of short-, medium- and long-term borrowings | 8,429 | 4,363 | 3,669 | 5,110 | 5,782 |

| + | New short-, medium- and long-term borrowings | 1,526 | 3,266 | 2,532 | 5,657 | 753 |

| = | Change in cash, cash equivalents and marketable securities (short-term investments) | (1,487) | 171 | (432) | 2,641 | 968 |

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISE

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 This adjustment is not necessary in by-function income statements, as explained in Chapter 3.

- 2 In accounting parlance, this is known as a “closing entry”.

- 3 Or investments in fixed assets.

- 4 When a company buys back some of its shares from some of its shareholders. For more details, see Chapter 37.

- 5 For details on consolidated accounts, see Chapter 6.

Chapter 6. GETTING TO GRIPS WITH CONSOLIDATED ACCOUNTS

A group-building exercise

This chapter deals with the basic aspects of consolidation that should be understood by anyone interested in corporate finance.

An analysis of the accounting documents of each individual company belonging to a group does not serve as a very accurate or useful guide to the economic health of the whole group. The accounts of a company reflect the other companies that it controls only through the book value of its shareholdings (revalued or written down, where appropriate) and the size of the dividends that it receives.

The goal of this chapter is to familiarise readers with the problems arising from consolidation. Consequently, we present an example-based guide to the main aspects of consolidation in order to facilitate analysis of consolidated accounts.

Section 6.1 CONSOLIDATION METHODS

Any firm that controls other companies exclusively should prepare consolidated accounts and a management report for the group.1

Consolidated accounts must be certified by the statutory auditors and, together with the group’s management report, made available to shareholders, debtholders and all other parties with a vested interest in the company.

Listed European companies have been required to use IFRS2 accounting principles for their consolidated financial statements since 2005 and groups from most other countries have been required or allowed to use these accounting standards since then.

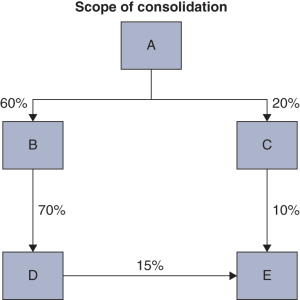

The companies to be included in the preparation of consolidated accounts form what is known as the scope of consolidation. The scope of consolidation comprises:

- the parent company;

- the companies in which the parent company has a material influence (which is assumed when the parent company holds at least 20% of the voting rights).

However, a subsidiary should not be consolidated when its parent loses the power to govern its financial and operating policies, for example when the subsidiary becomes subject to the control of a government, a court or an administration. Such subsidiaries should be accounted for at fair market value.

For instance, let us consider a company with a subsidiary that appears on its balance sheet with an amount of 20. Consolidation entails replacing the historical cost of 20 with all or some of the assets, liabilities and equity of the company being consolidated.

There are two methods of consolidation which are used, depending on the strength of the parent company’s control or influence over its subsidiary:

| Type of relationship | Type of company | Consolidation method |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Subsidiary | Full consolidation3 |

| Significant influence | Associate | Equity method |

We will now examine each of these two methods in terms of its impact on sales, net profit and shareholders’ equity.

1/ FULL CONSOLIDATION

The accounts of a subsidiary are fully consolidated if the latter is controlled by its parent. Control is defined as the ability to direct the strategic financing and operating policies of an entity so as to access benefits. It is presumed to exist when the parent company:

- holds, directly or indirectly, over 50% of the voting rights in its subsidiary;

- holds, directly or indirectly, less than 50% of the voting rights but has power over more than 50% of the voting rights by virtue of an agreement with other investors;

- has power to govern the financial and operating policies of the subsidiary under a statute or an agreement;

- has power to cast the majority of votes at meetings of the board of directors; or

- has power to appoint or remove the majority of the members of the board.

The criterion of exclusive control is the key factor under IFRS standards. It can encompass companies in which only a minority is held (or even no shares at all!) provided the subsidiary is deemed to be controlled by the parent company.

As its name suggests, full consolidation consists of transferring all the subsidiary’s assets, liabilities and equity to the parent company’s balance sheet and all the revenues and costs to the parent company’s income statement.

The assets, liabilities and equity thus replace the investments held by the parent company, which therefore disappear from its balance sheet.

That said, when the subsidiary is not controlled exclusively by the parent company, the claims of the other “minority” shareholders on the subsidiary’s equity and net income also need to be shown on the consolidated balance sheet and income statement of the group.

Assuming there is no difference between the book value of the parent’s investment in the subsidiary and the share of the book value of the subsidiary’s equity,4 full consolidation works as follows.

- On the balance sheet:

- the historical cost amount of the shares in the consolidated subsidiary held by the parent is eliminated from the parent company’s balance sheet and the same amount is deducted from the parent company‘s reserves;

- the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities are added item by item to the parent company’s balance sheet;

- the subsidiary’s equity (including net income) is then allocated between the interests of the parent company, which is added to its reserves, and those of minority investors in the subsidiary (if the parent company does not hold 100% of the capital), called minority interests, which is added on an individualised line of shareholders’ equity below the group’s share of shareholders’ equity.

- On the income statement, all the subsidiary’s revenues and charges are added item by item to the parent company’s income statement. The subsidiary’s net income is then broken down into:

- the portion attributable to the parent company, which is added to the parent company’s net income to create the line net income attributable to shareholders or group share net income;

- the portion attributable to third-party investors, which is shown on a separate line of the income statement under the heading “minority interests”.

From a solvency standpoint, minority interests certainly represent shareholders’ equity. But from a valuation standpoint, they add no value to the group since minority interests represent shareholders’ equity and net profit attributable to third parties and not to shareholders of the parent company.

To illustrate the full consolidation method, consider the following example assuming that the parent company owns 75% of the subsidiary company.

The original non-consolidated balance sheets are as follows:

| Parent company’s balance sheet | Subsidiary’s balance sheet | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment in the subsidiary5 | 15 | Shareholders’ equity | 70 | Assets | 28 | Shareholders’ equity | 20 | |||

| Other assets | 57 | Liabilities | 2 | Liabilities | 8 | |||||

In this scenario, the consolidated balance sheet would be as follows:

| Consolidated balance sheet | |||