**Section III. VALUE

Chapter 26. VALUE AND CORPORATE FINANCE

Chapter 26

VALUE AND CORPORATE FINANCE

No, Sire, it’s a revolution!

This section presents the concepts and theories that underpin all important financial decisions. In particular, we will examine their impact on value, keeping in mind that basically to maximise a value, we must minimise a cost. The chapters in this section will introduce you to the investment decision processes within a firm and their impact on the overall value of the company.

Section 26.1 THE FINANCIAL PURPOSE OF A COMPANY IS TO CREATE VALUE

1/ INVESTMENT AND VALUE

The accounting rules we looked at in Chapter 4 showed us that an investment is a use of funds, but not a reduction in the value of assets. We will now go one step further and adopt the viewpoint of the financial manager for whom a sufficiently profitable investment is one that increases the value of capital employed.

We shall see that a key element in the theory of markets in equilibrium is the market value of capital employed. This theory underscores the direct link between the return on a company’s investments and that required by investors buying the financial securities issued by the company.

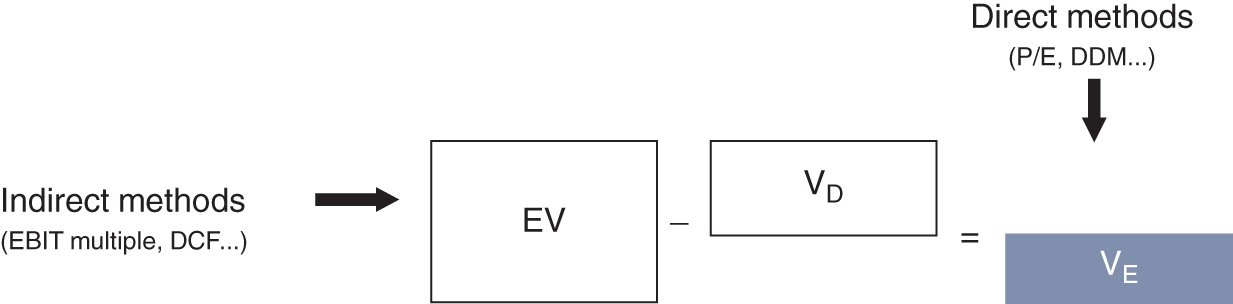

The true measure of an investment policy is the effect it has on the value of capital employed. This concept is sometimes called “enterprise value”, a term our reader should not confuse with the value of equity (capital employed less net debt). The two are far from the same!

Hence the importance of every investment decision, as it can lead to three different outcomes:

- Where the expected return on an investment is higher than that required by investors, the value of capital employed rises instantly. An investment of 100 that always yields 15% in a market requiring a 10% return is worth 150 (100 × 15% / 10%). The value of capital employed thus immediately rises by 50.

- Where the expected return on the investment is equal to that required by investors, there is neither gain nor loss. The investors put in 100, the investment is worth 100 and no value has been created.

- Where the expected return on an investment is lower than that required by investors, they have incurred a loss. If, for example, they invested 100 in a project that in the end should only yield 6% to perpetuity, then the value of the project is only 60 (100 × 6% / 10%), giving an immediate loss in value of 40.

- Value remains constant if the expected rate of return is equal to that required by the market.

- An immediate loss in value results if the return on the investment is lower than that required by the market.

- Value is effectively created if the expected rate of return is higher than that required by the market.

The resulting gain or loss is simply the positive or negative net present value that must be calculated when valuing any investment. All this means, in fact, is that if the investment was fairly priced, then nothing changes for the investor. If it was “too expensive”, the investors take a loss, but if it was a good deal, they earn a profit.

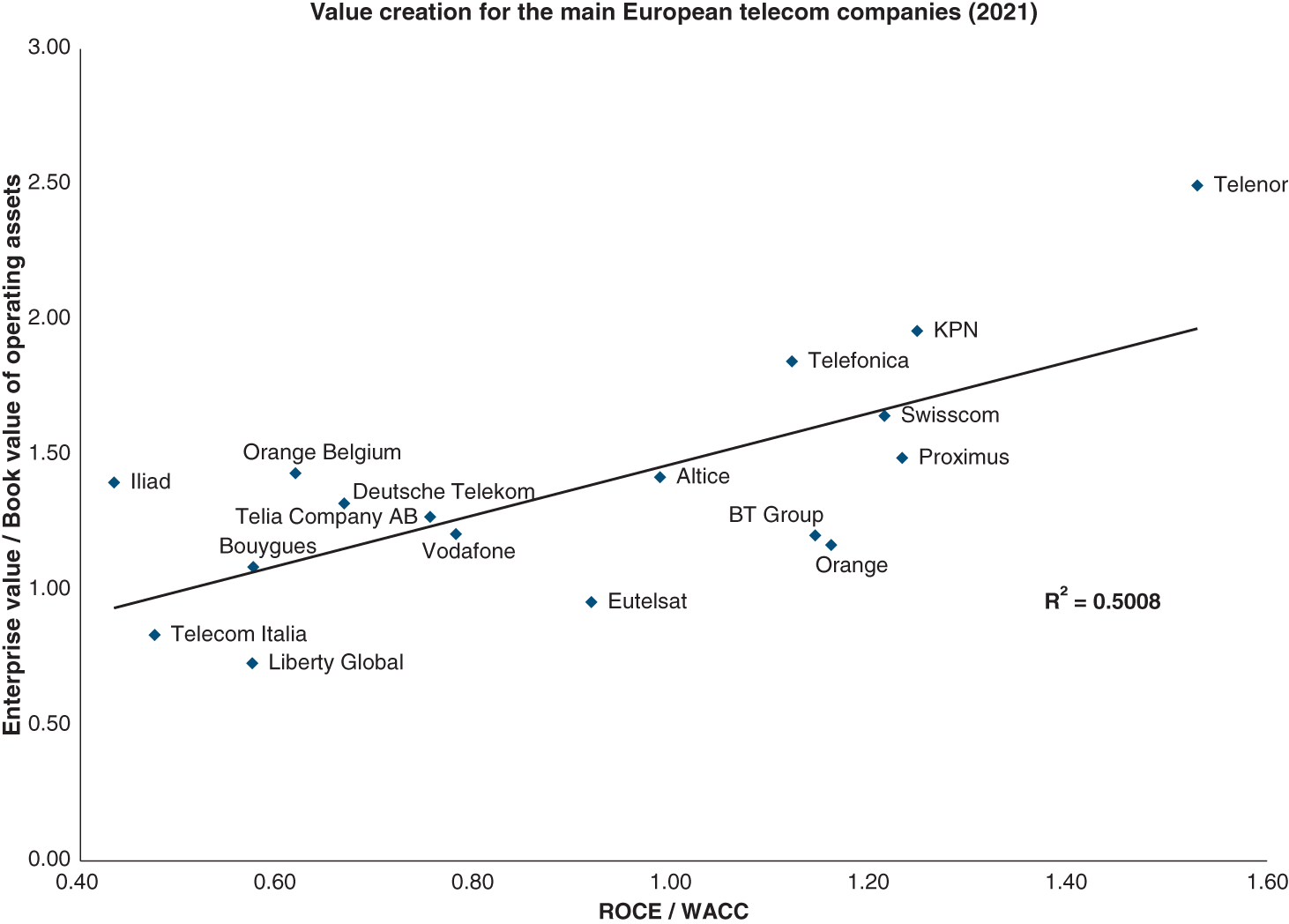

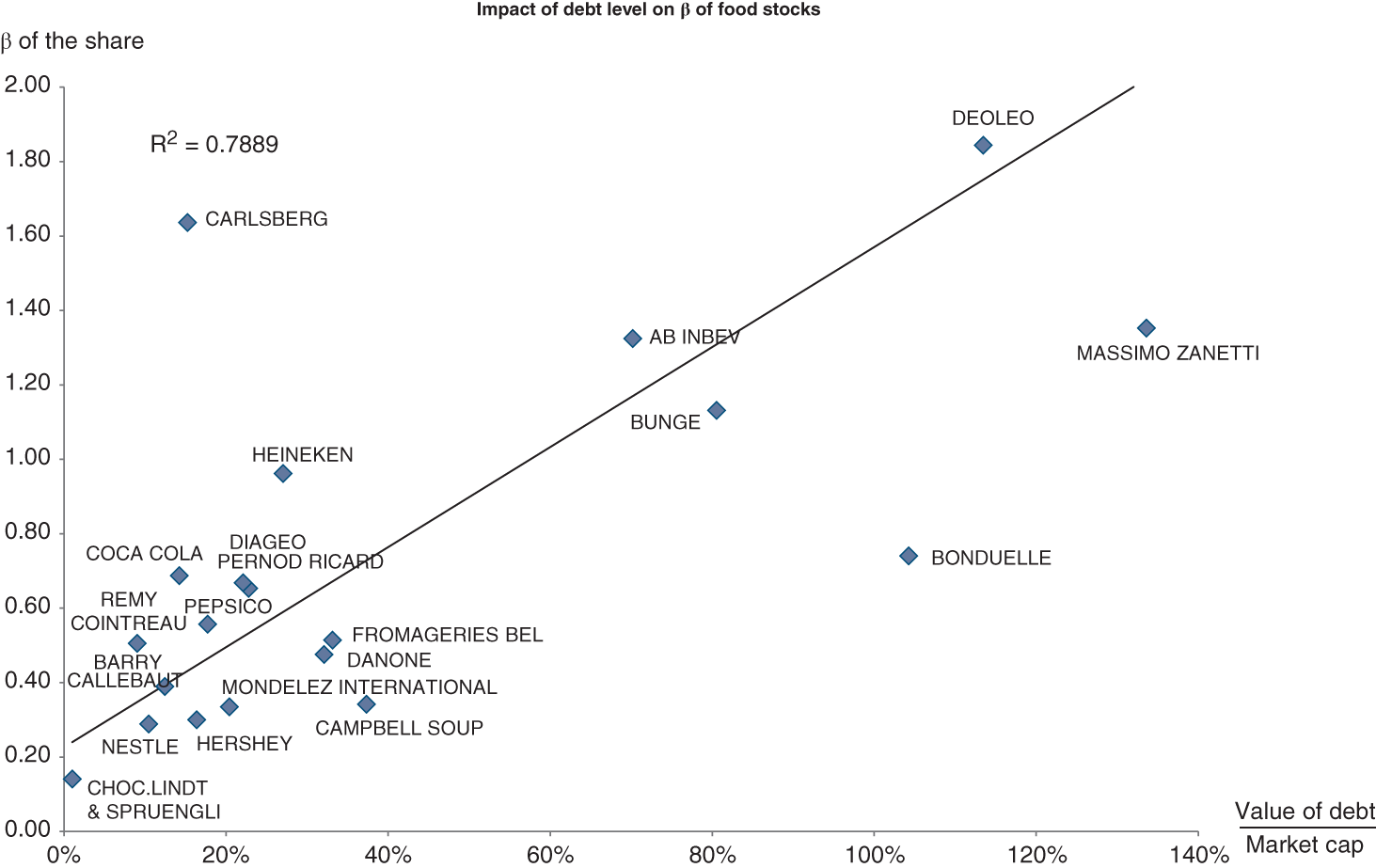

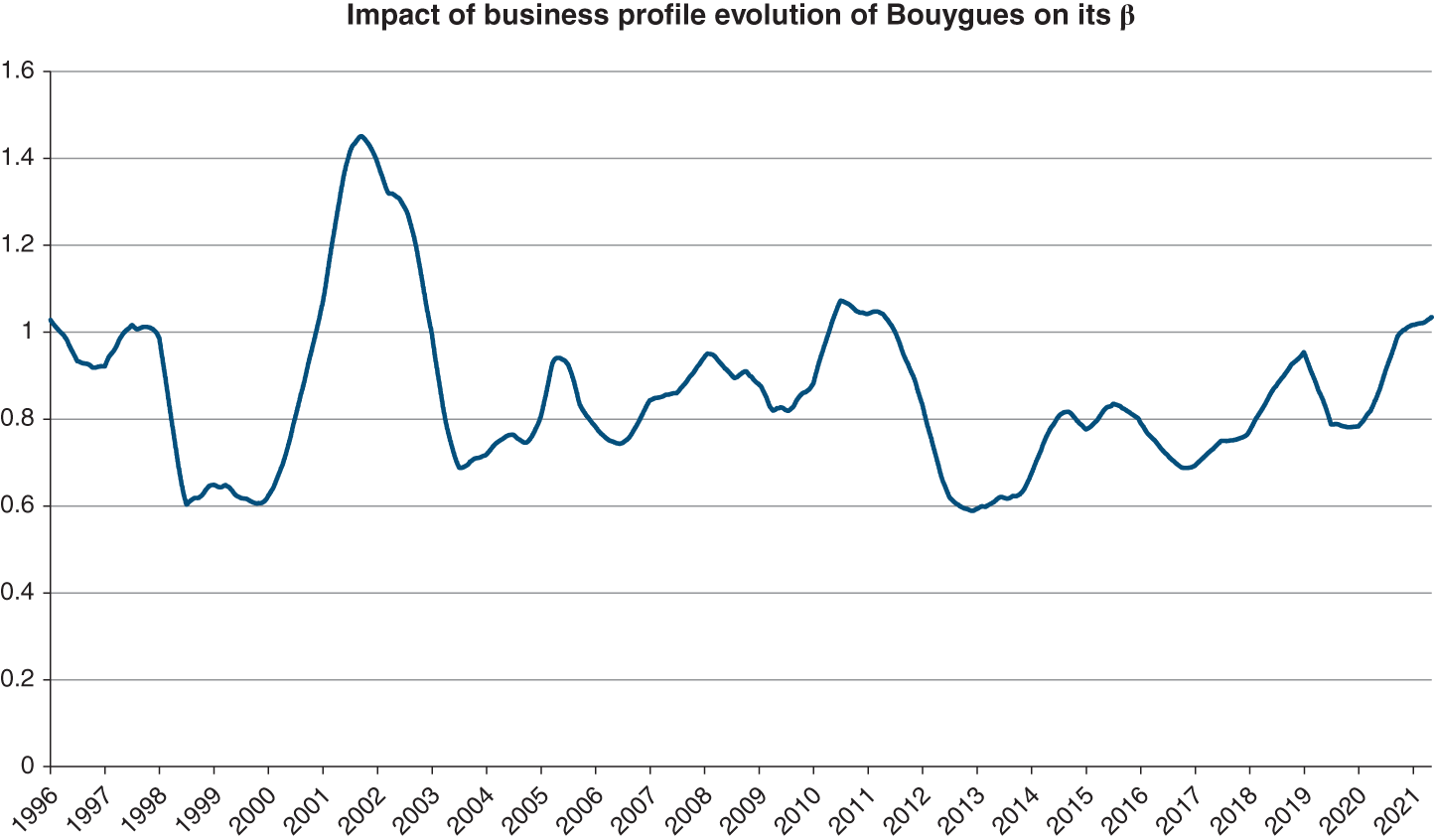

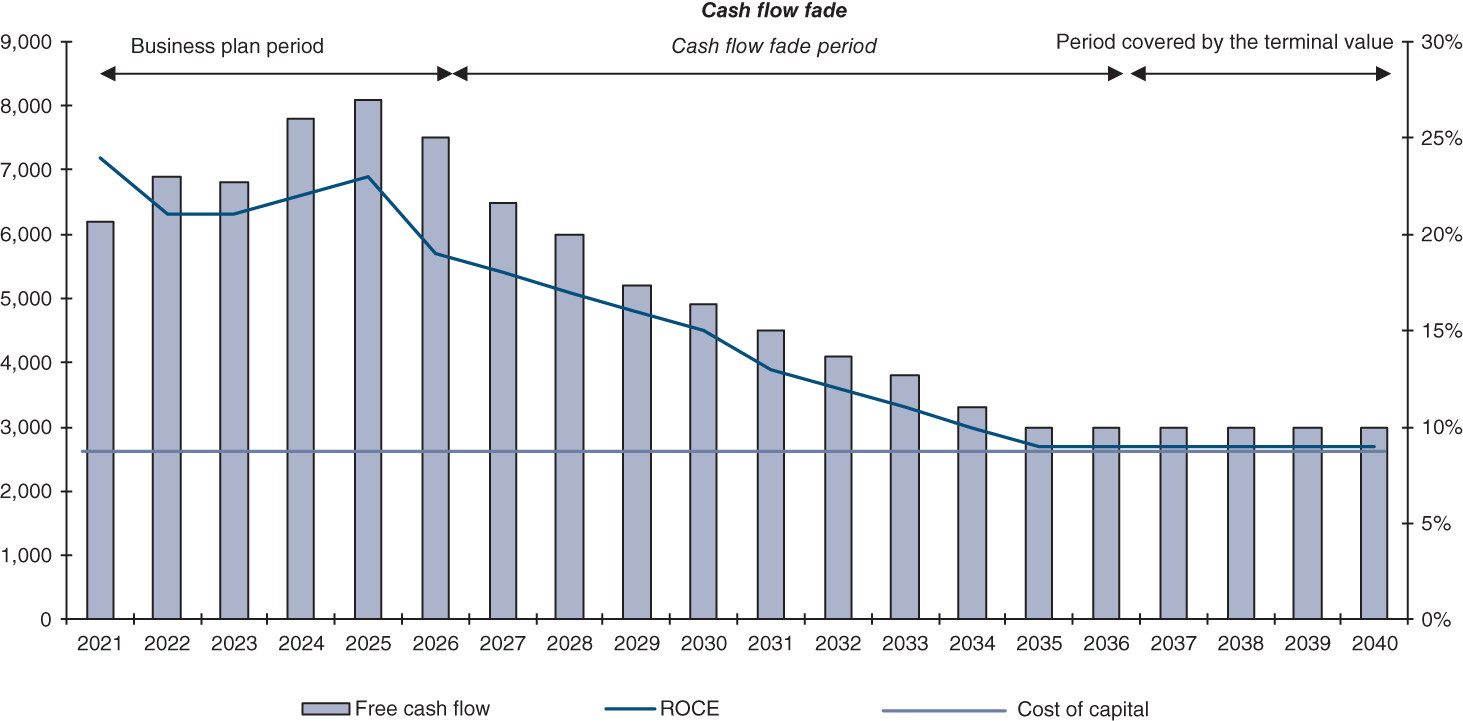

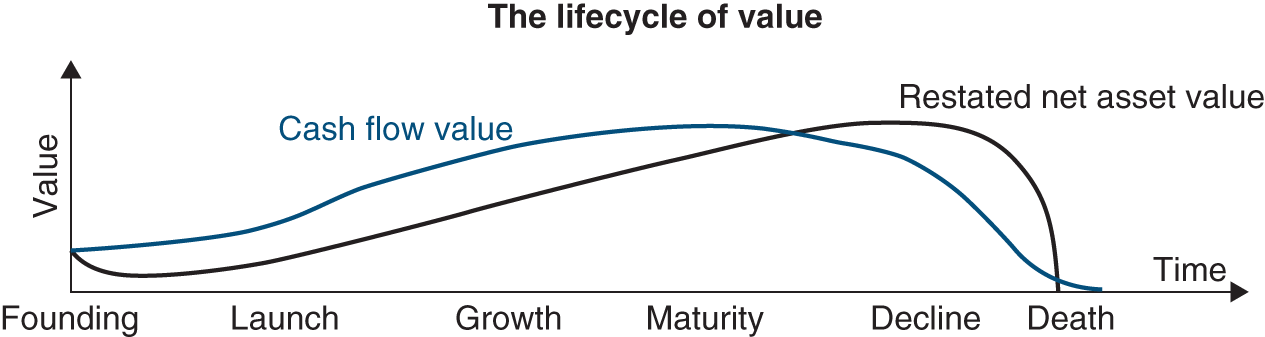

The graph below shows that value is created (the value of capital employed exceeds its book value) when return on capital employed exceeds the weighted average cost of capital, i.e. the rate of return required by all suppliers of funds to the company.

Source: Data from Exane BNP Paribas

2/ THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COMPANIES AND THE FINANCIAL WORLD

In the preceding chapters we examined the various financial securities that make up the debt issued by a company from the point of view of the investor. We shall now cross over to the other side to look at them from the issuing company’s point of view.

- Each amount contributed by investors represents a resource for the company.

- The financial securities held by investors as assets are recorded as liabilities in the company’s balance sheet.

- And, most importantly, the rate of return required by investors represents a financial cost to the company.

At the financial level, a company is a portfolio of assets financed by the securities issued on financial markets. Its liabilities, i.e. the securities issued and placed with investors, are merely a financial representation of the industrial or operating assets. The financial manager’s job is to ensure that this representation is as transparent as possible.

What is the role of the investor?

Investors play an active role when securities are issued, because they can simply refuse to finance the company by not buying the securities. In other words, if the financial manager cannot come up with a product offering a risk/reward trade-off acceptable to investors, then the lack of funding will eventually push the company into bankruptcy.

We shall see that when this happens, it is often too late. However, the financial system can impose a sanction that is far more immediate and effective: the valuation of the securities issued by the company.

Financial markets continuously value the securities in issue. In the case of debt instruments, rating agencies assign a credit rating to the company, thus determining the value of its existing debt and the terms of future loans. Similarly, by valuing the shares issued the market is, in fact, valuing the company’s equity.

So how does this mechanism work?

If a company cannot satisfy investors’ risk/reward requirements, it is penalised by a lower valuation of its capital employed and, accordingly, its equity. Suppose a company offers the market an investment of 100 that is expected to yield 10 every year over a period long enough to be considered to perpetuity.1 However, the actual yield is only 5 and shows no sign of improvement. The disappointed investors who were expecting a 10% return will try to get rid of their investment. The equilibrium price will be 50, because at this price investors receive a return of 10% (5 / 50) and it is no longer in their interests to sell. But by now it is too late.

Investors who are unhappy with the offered risk/reward trade-off sell their securities, thus depressing the value of the securities issued and of capital employed, since the company’s investments are not profitable enough with regard to their risk. True, the investor takes a hit, but it is sometimes wiser to cut one’s losses.

In doing so, he is merely giving tit for tat: an unhappy investor will sell off his securities, thus lowering prices. Ultimately, this can lead to financing difficulties for the company, and increased dilution for the shareholder.

The “financial sanction” affects first and foremost the valuation of the company via the valuation of its shares and debt securities.

As long as the company is operating normally, its various creditors are fairly well protected.2 Most of the fluctuation in the value of its debt stems from changes in interest rates, so changes in the value of capital employed derive mainly from changes in the value of equity. We see why the valuation of equity is so important for any normally developing company. This does not apply just to listed companies: unlisted companies are also affected whenever they envisage divestments, alliances, transfers or capital increases.

The role of creditors looms large only when the company is in difficulty. The company then “belongs” to the creditors, and changes in the value of capital employed derive from changes in the value of the debt, by then generally lower than its nominal value. This is where the creditors come into play.

3/ IMPLICATIONS

Since we consider that creating value is the overriding financial objective of a company, it follows that:

- A financial decision harms the company if it reduces the value of capital employed.

- A decision is beneficial to the company if it increases the value of capital employed.

A word of caution, however! Contrary to appearances, this does not mean that every good financial decision increases earnings or reduces costs.

Remember, we are not in the realm of accounting, but in that of finance – in other words, value. An investment financed by cash from operations may increase earnings, but could still be insufficient with regard to the return expected by the investor who, as a result, has lost value.

Certain legal decisions, such as restricting a shareholder’s voting rights, have no immediate impact on the company’s earnings or cash, yet may reduce the value of the corresponding financial security and thus prove costly to the holder of the security.

We cannot emphasise this aspect enough, and insist that you adopt this approach before immersing yourselves further in the raptures of financial theory.

Section 26.2 VALUE CREATION AND MARKETS IN EQUILIBRIUM

1/ A CLEAR THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

We have just said that a company is a portfolio of assets and liabilities, and that the concepts of cost and revenue should be seen within the overall framework of value. Financial management consists of assessing the value created for the company’s fund providers.

Can the overall value of the company be determined by an optimal choice of assets and liabilities? If so, how can you be sure of making the right decisions to create value?

You may already have raised the following questions:

- Can the choice of financing alone increase the value of the firm? Is capital employed financed half by debt and half by equity worth more than if it were financed wholly through equity?

- Can the entrepreneur increase the value of capital employed – that is, influence the market’s valuation of it – by either combining independent industrial and commercial investments or implementing a shrewd financing policy?

If your answer to all these questions is yes, you attribute considerable powers to financial managers. You consider them capable of creating value independently of their industrial and commercial assets.

And yet, the equilibrium theory of markets is very clear:

We now provide a more formal explanation of the above rule, which is based on arbitrage.

To this end, let us simplify things by imagining that there are just two options for the future: either the company does well or it does not. We shall assign an equal probability to each of these outcomes.

We shall see how the free cash flow of three companies varies in our two states of the world:

FREE CASH FLOW

| State of the world: bad | State of the world: good | |

|---|---|---|

| A | 200 | 1,000 |

| B | 400 | 500 |

| G | 600 | 1,500 |

Note that the sum of the free cash flows of companies A and B is equal to that of company G. We shall demonstrate that the share price of company G is equal to the sum of the prices of shares of B and A.3 To do so, let us assume that this is not the case, and that VA + VB > VG (where VA, VB and VG are the respective share prices of A, B and G).

You will see that no speculation is necessary here to earn money. Taking no risk, you sell short one share of A and one share of B and buy one share of G. You immediately receive VA + VB − VG > 0; yet, regardless of the company’s fortunes, the future negative flows of shares of A and B (sold) and positive flows of shares of G (bought) will cancel each other out. You have realised a gain through arbitrage.

The same method can be used to demonstrate that VA + VB < VG is not possible in a market that is in equilibrium. We therefore deduce that VA + VB = VG. It is thus clear that a diversified company, in our case G, is not worth more than the sum of its two divisions A and B.

Let us now look at the following three securities:

FREE CASH FLOW

| Company | State of the world: bad | State of the world: good |

|---|---|---|

| C | 100 | 1,000 |

| D | 500 | 500 |

| E | 600 | 1,500 |

According to the rule demonstrated above, VC + VD = VE. Note that security D could be a debt security and C share capital. E would then be the capital employed. The value of capital employed of an indebted company (V(C+D)) can be neither higher nor lower than that of the same company if it had no debt (VE).

The additivity rule is borne out in terms of risk: if the company takes on debt, then financial investors can stabilise their portfolios by adding less risky securities. Conversely, they can go into debt themselves in order to buy less risky securities. So why should they pay for an operation they can carry out themselves at no cost?

This reasoning applies to diversification as well. If its only goal is to create financial value without generating industrial and commercial synergies, then there is no reason why investors should entrust the company with the diversification of their portfolio.

2/ ILLUSTRATION

Are some asset combinations worth more than the value of their individual components, regardless of any industrial synergies arising when some operations are common to several investment projects? In other words, is the whole worth more than the sum of its parts (2 + 2 = 5)?

Or again, is the required rate of return lower simply because two investments are made at the same time?

Company managers are fuzzy on this issue. They generally answer in the negative, although their actual investment decisions tend to imply the opposite. Take Prisma (a publisher of magazines), for example, which was bought by Vivendi in 2021. If financial synergies exist, one would have to conclude that the required rate of return in the magazine publishing industry differs depending on whether the company is independent or part of a group. Prisma would therefore appear to be worth more as part of the Vivendi group than on a standalone basis.

The question is not as specious at it seems. In fact, it raises a fundamental issue. If the required return on Prisma has fallen since it became part of Vivendi, its financing costs will have declined as well, giving it a substantial, permanent and possibly decisive advantage over its competitors.

Diversifying corporate activities reduces risk, but does it also reduce the rate of return required by investors?

Suppose the required rate of return on a company producing a single product is 10%. The company decides to diversify by acquiring a company of the same size on which the required rate of return is 8%. Will the required rate of return on the new group be lower than (10% + 8%) / 2 = 9% because it carries less risk than the initial single-product company?

We must not be misled into believing that a lower degree of risk must always be matched by a lower required rate of return. On the contrary: markets only remunerate systematic or market risks, i.e. those that cannot be eliminated by diversification. We have seen that unsystematic or specific risks, which investors can eliminate by diversifying their portfolios, are not remunerated. Only non-diversifiable risks related to market fluctuations are remunerated. This point was discussed in Chapter 18.

Since diversifiable risks are not remunerated, a company’s value remains the same whether it is independent or part of a group. Prisma is not worth more now that it has become a division of Vivendi. All else being equal, the required rate of return in the robot sector is the same whether the company is independent or belongs to a group.

On the other hand, Prisma’s value will increase if, and only if, Vivendi’s management allows it to improve its return on capital employed.

Value is created only when the sum of cash flows from the two investments is higher because they are both managed by the same group. This is the result of industrial synergies (2 + 2 = 5), and not financial synergies, which do not exist.

The large groups that indulged in a spate of financial diversifications in the 1960s have since realised that these operations were unproductive and frequently loss-making. Diversification is a delicate art that can only succeed if the diversifying company already has expertise in the new business. Combining investments per se does not maximise value, unless industrial synergies exist. Otherwise, an investment is either “good” or “bad” depending on its return compared to the required rate of return.

In other words, managers must act on cash flows; they cannot influence the discount rate applied to them unless they reduce their risk exposure.

3/ A FIRST CONCLUSION

The value of the securities issued by a company is not connected to the underlying financial engineering. Instead, it simply reflects the market’s reaction to the perceived profitability and risk of the industrial and commercial operations.

The equilibrium theory of markets leads us to a very simple and obvious rule, that of the additivity of value, which in practice is frequently neglected. Regardless of developments in financial criteria, in particular earnings per share, value cannot be created simply by adding (diversifying) or reducing value that is already in equilibrium.

We emphasise that this rule applies to listed and unlisted companies alike, a fact that the latter are forced to face at some point. Capital employed always has an equilibrium value, and the entrepreneur must ultimately recognise it.

This approach should be incorporated into the methodology of financial decision-making. Some strategies are based on maximising other types of value, for example the capability to cause harm to competitors. They are particularly risky and are outside the conceptual framework of corporate finance.

Does this mean that, ultimately, financing or diversification policies have no impact on value?

Our aim is not to encourage nihilism, merely a degree of humility.

Section 26.3 VALUE AND ORGANISATION THEORIES

1/ LIMITS OF THE EQUILIBRIUM THEORY OF MARKETS

The equilibrium theory of markets offers an overall framework, but it completely disregards the immediate interests of the various parties involved, even if their interests tend to converge in the medium term.

Since the equilibrium theory demonstrates that finance cannot change the size of the capital employed, but only how it is divided up, it follows that many financial problems stem from the struggle between the various players in the financial realm.

First and foremost we have the various parties providing funding to the company. To simplify matters, they can be divided into two categories: shareholders and creditors. But we shall soon see that, in fact, each type of security issued gives rise to its own interest group: shareholders, preferred creditors, ordinary creditors, subordinated creditors, investors in convertible bonds, etc. Further on in this chapter, we shall see that interests may even diverge within the same funding category.

One example should suffice. According to the equilibrium theory of markets, investing at the required rate of return does not change the value of capital employed. But if the investment is very risky and, therefore, potentially very profitable, creditors, who earn a fixed rate, will only see the increased risk without a corresponding increase in their return. The value of their claims thus decreases, to the benefit of shareholders whose shares increase by the same amount, the value of capital employed remaining the same. And yet, this investment was made at its equilibrium price.

This is where the financial manager comes into play! Their role is to distribute value between the various parties involved. In fact, the financial manager must be a negotiator at heart.

But let’s not forget that the managers are stakeholders as well. Since portfolio theory presupposes good diversification, there is a distinction between investors and managers, who have divergent interests with different levels of information (internal and external). This last point calls into question one of the basic tenets of the equilibrium theory, which is that all parties have access to the same information (see Chapter 15).

2/ SIGNALLING THEORY AND ASYMMETRIC INFORMATION

Signalling theory is based on two basic ideas:

- the same information is not available to all parties: the managers of a company always have more information than investors;

- even if the same information were available to all, it would not be perceived in the same way, a fact frequently observed in everyday life.

Thus, it is unrealistic to assume that information is fairly distributed to all parties at all times, i.e. that it is symmetrical as in the case of efficient markets. On the contrary, asymmetric information is the rule.

This can clearly raise problems. Asymmetric information may lead investors to undervalue a company. As a result, its managers might hesitate to increase its capital because they consider the share price to be too low. This may mean that profitable investment opportunities are lost for lack of financing, or that the existing shareholders find their stake adversely diluted because the company has launched a capital increase anyway.

This is where the communication policy comes into its own. Basing financial decisions on financial criteria alone is not enough: managers also have to convince the markets that these decisions are wise.

The cornerstone of the financial communications policy is the signal the managers of a company send to investors.

Contrary to what many financial managers and CEOs believe, the signal is neither an official statement nor a confidential tip. It is a real financial decision, taken freely and which may have negative financial consequences for the decision-maker if it turns out to be wrong.

After all, investors are far from naive and they take each signal with the requisite pinch of salt. Three points merit attention:

- Investors’ first reaction is to ask themselves why the signal is being sent, since nothing comes for free in the financial world. The signal will be perceived negatively if the issuer’s interests are contrary to those of investors. For example, the sale of a company by its majority shareholder would, in theory, be a negative signal for the company’s growth prospects. Managers must therefore persuade the buyer of the contrary or provide a convincing explanation for the disposal.

Similarly, owner-managers cannot fool investors by praising the merits of a capital increase without subscribing to it!

However, the market will consider the signal to be credible if it deems that it is in the issuer’s interest that the signal be correct. This would be the case, for example, if the managers reinvest their own assets in the company (the signal is even greater if the entrepreneur takes debt to invest).

- The reputation of management and its communications policy certainly play a role, but we must not overestimate their importance or lasting impact.

- The market supervisory authorities stand ready to impose penalties on the dissemination of misleading information or insider trading. If investors, particularly international investors, believe that supervision is effective, they will factor this into their decisions. That said, some managers may be tempted to send incorrect signals in order to obtain unwarranted advantages. For example, they could give overly optimistic guidance on their company’s prospects in order to push up share prices. However, markets catch on to such misrepresentations quickly and react to incorrect signals by piling out of the stock.

In such a context, the “watchdog” role played by the market authorities is crucial and the recent past has shown that the authorities intend to assume it in full. Such rigour is essential if we are to have the best possible financial markets and the lowest possible financing costs for companies.

Financial managers must therefore always consider how investors will react to their financial decisions. They cannot content themselves with wishful thinking, but must make a rational and detailed analysis of the situation to ensure that their communication is convincing.

Signalling theory says that corporate financial decisions (e.g. financing, dividend payout) are signals sent by the company’s managers to investors. It examines the incentives that encourage good managers to issue the right signals and discourage managers of ailing companies from using these same signals to give a misleading picture of their company’s financial health.

- investments are not maximised because the cost of financing is too high;

- the choice of financing is skewed in favour of sources (such as debt) where there is less information asymmetry.

Stephen Ross initiated the main studies in this field in 1977.

3/ AGENCY THEORY

Agency theory says that a company is not a single, unified entity. It considers a company to be a legal arrangement that is the culmination of a complex process in which the conflicting objectives of individuals, some of whom may represent other organisations, are resolved by means of a set of contractual relationships.

On this basis, a company’s behaviour can be compared to that of a market, insofar as it is the result of a complex balancing process. Taken individually, the various stakeholders in the company have their own objectives and interests that may not necessarily be spontaneously reconcilable. As a result, conflicts may arise between them, especially since our modern corporate system requires that the suppliers of funds entrust the managers with the actual administration of the company.

Agency theory analyses the consequences of certain financial decisions in terms of risk, profitability and, more generally, the interests of the various parties. It shows that some decisions may go against the simple criteria of maximising the wealth of all parties to the benefit of just one of the suppliers of funds.

To simplify, we consider that an agency relationship exists between two parties when one of them, the agent, carries out an activity on behalf of the other, the principal. The agent has been given a mandate to act or take decisions on behalf of the principal. This is the essence of the agency relationship.

This very broad definition allows us to include a variety of domains, such as the resolution of conflicts between:

- executive shareholders/non-executive shareholders;

- non-shareholder executives/shareholders;

- creditors/shareholders.

Shareholders give the company executives a mandate to manage to the best of their ability the funds that have been entrusted to them. However, their concern is that the executives could pursue objectives other than maximising the value of the equity, such as increasing the company’s size at the cost of profitability, minimising the risk to capital employed by rejecting certain investments that would create value but could put the company in difficulty if they fail, etc.

One way of resolving such conflicts of interest is to use stock options, performance shares (shares offered to management depending on certain targets being reached) or free shares, thus linking management compensation to share performance (see Chapter 43).

Debt plays a role as well, since it has a constraining effect on managers and encourages them to maximise cash flows so that the company can meet its interest and principal payments. Failing this, the company risks bankruptcy and the managers lose their jobs. Maximising cash flows is in the interests of shareholders as well, since it raises the value of shareholders’ equity. Thus, the interests of management and shareholders converge. Maybe debt is the modern whip! This is sometimes referred to as “the discipline of debt”.

The diverging interests of the various parties generate a number of costs called “agency costs”. These comprise:

- the cost of monitoring managers’ efforts (control procedures, audit systems, performance-based compensation) to ensure that they correspond to the principal’s objectives. Stock options and free shares represent an agency cost since they are exercised at less than the going market price for the stock;

- the costs incurred by the agents to vindicate themselves and reassure the principals that their management is effective, such as the publication of annual reports, the organisation of regular meetings with investors;

- residual costs.

The main references in this field are Jensen and Meckling (1976), Grossman and Hart (1980) and Fama (1980). Their research aimed to provide a scientific explanation of the relationship between managers and shareholders and its impact on corporate value.

This research forms the intellectual foundation on which the concept of corporate governance was built (see Chapter 43).

4/ FREE RIDERS

We saw above that the interests of the different types of providers of funds may diverge, but so may those of members of the same category.

This means, first, that there must be several – usually a large number – of investors in the same type of security and, second, that a specific operation is undertaken implying some sort of sacrifice, at least in terms of opportunity cost, on the part of the investors in these securities.

As a result, when considering a financial decision, one must examine whether free riders exist and what their interests might be.

Below are two examples:

- Responding to a takeover bid: if the offer is motivated by an expectation of synergies between the bidding company and its target, then the business combination will create value. This means that it is in the general interest of all parties for the bid to succeed and for the shareholders to tender their shares. However, it would be in the individual interest of these same shareholders to hold on to their shares in order to benefit fully from the future synergies.

- Bank A holds a small claim on a cash-strapped company that owes money to many other banks. It would be in the interests of the banks as a whole to grant additional loans to tide the company over until it can pay them back, but the interest of our individual bank would be to let the other banks, which have much larger exposure, advance the funds themselves. Bank A would thus hold a better-valued existing claim without incurring a discount on the new credits granted.

Section 26.4 HOW CAN WE CREATE VALUE?

Before we begin simulating different rates of return, we would like to emphasise once again that a project, investment or company can only realise extraordinary returns if it enjoys a strategic advantage. The equilibrium theory of markets tells us that under perfect competition, the net present value of a project should be nil. If a financial manager wants to advise on investment choices, he will no doubt have to make a number of calculations to estimate the future return of the investment. But he will also have to look at it from a strategic point of view, incorporating the various economic theories he has learned.

A project’s real profitability can only be explained in terms of economic rent – that is, a position in which the return obtained on investments is higher than the required rate of return given the degree of risk. The essence of all corporate strategies is to obtain economic rents – that is, to generate imperfections in the product market and/or in factors of production, thus creating barriers to entry that the corporate managers strive to exploit and defend.

But don’t fool yourself, economic rents do not last forever. Returns that are higher than the required rate, taking into account the risk exposure, inevitably attract the attention of competitors (Tesla) or of the antitrust authorities, as in the case of Google. Sooner or later, deregulation and technological advances put an end to them. There are no impregnable fortresses, only those for which the right angle of attack has not yet been found.

A strategic analysis of the company is thus essential to put the figures in their economic and industrial context, as we explained in Chapter 8.

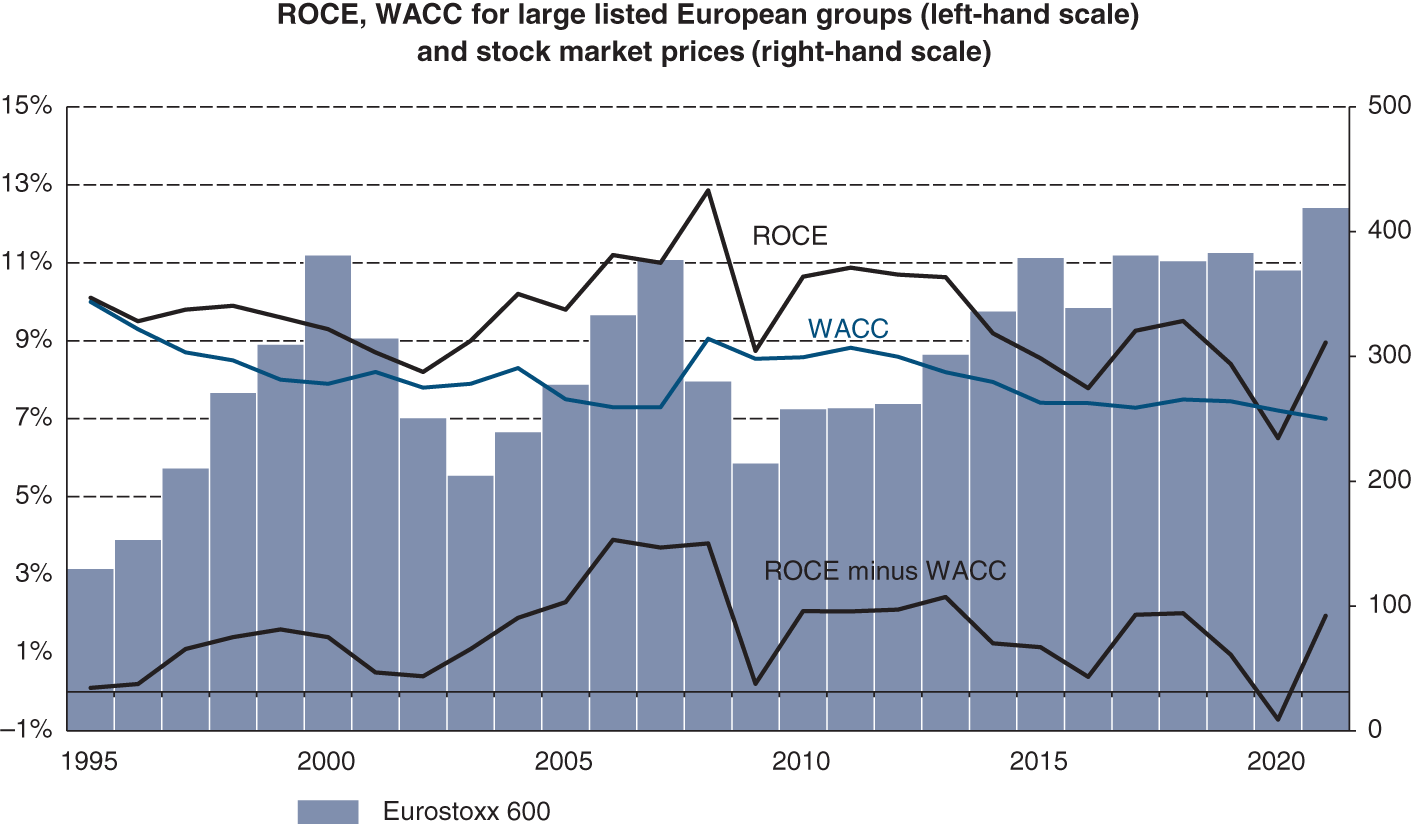

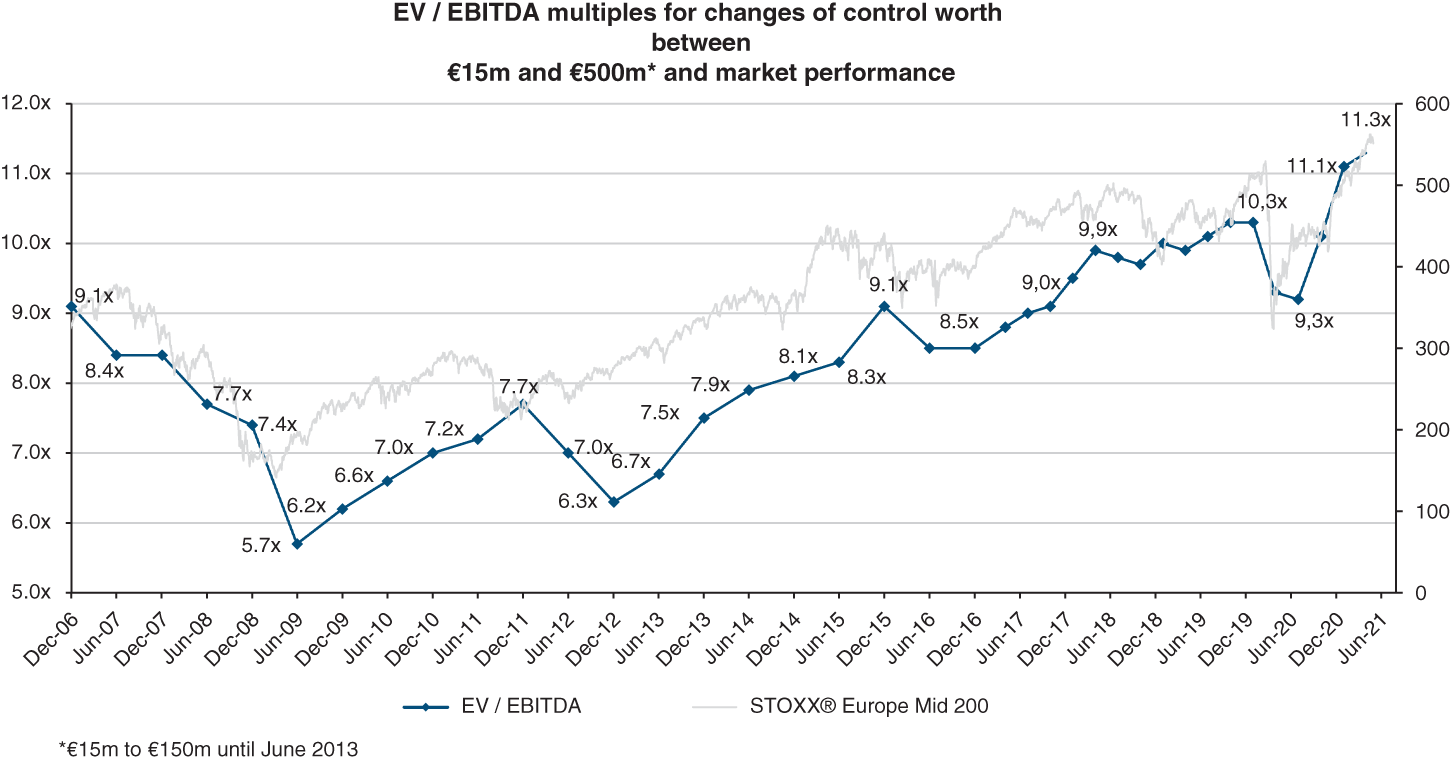

Source: Exane BNP Paribas, Factset

We insist on the consequences of a good strategy. When based on accurate forecasts, it immediately boosts the value of capital employed and, accordingly, the share price. This explains the difference between the book value of capital employed and its market value.

Rather than rising gradually as the returns on the investment accrue, the share price adjusts immediately so that the investor receives the exact required return, no more, no less. And if everything proceeds smoothly thereafter, the investment will generate the required return until expectations prove too optimistic or too pessimistic.

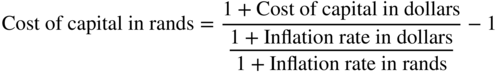

Section 26.5 VALUE AND TAXATION

Depending on the company’s situation, certain types of securities may carry tax benefits. You are certainly aware that tax planning can generate savings, thereby creating value or more likely preventing the loss of value. Reducing taxes is a form of value creation for investors and shareholders. All else being equal, an asset with tax-free flows is worth more than the same asset subject to taxation.

Better to have a liability with cash outflows that can be deducted from taxes than the same liability with outflows that are not deductible.

This goes without saying, and any CFO will do their best to reduce tax payments, while conforming with the spirit (and not just the strict letter) of the law. Society as a whole is no longer as forgiving of irresponsible behaviour in this domain.

They must carefully examine the impact each financial decision will have on taxes.

Our experience tells us that taking a financial decision solely on the basis of tax considerations is rarely the right thing to do. The failure of the AstraZeneca–Pfizer attempted merger, which was mainly based on fiscal considerations, is a good illustration of this.

Section 26.6 A BREAK BEFORE MOVING TO THE NEXT STEP

This chapter is dense and we would advise readers who may be discovering this information for the first time, to reread and meditate on it.

They may have been surprised or shocked to see us define value creation as the financial objective of the company, so much so that this term, which has been popular since the early 1990s, has become a mandatory part of the discourse of most managers, sometimes giving the impression that it is just management speak.

Value creation is not synonymous, as it is sometimes hastily accused of being, with redundancies, plant closures, cost cutting, and neglect of the environment, labour laws and human dignity. Quite the contrary! When we look at the list of groups that have created lasting value for their shareholders, often over very long periods, we immediately see that these are companies that have constantly innovated, grown, created markets, responded to new needs, hired and trained staff, built loyalty, created strong ties with their customers – such as Dassault Systemes, Apple, Tesla, SEB, BMW and so on.

A cost-cutting strategy can only be temporary. It cannot create lasting shareholder value unless it quickly leads to a strategy of profitable growth (as Kraft Heinz has unwillingly demonstrated).

Creating value means avoiding destroying it. In other words, avoiding bad decisions, avoiding the loss through waste of part of a scarce resource which you have been entrusted with, equity, which could have been better allocated elsewhere, and for the benefit of the many. One should avoid penalising personal savings, which have taken risks.

As we have said, and this is one of the main concepts of this chapter, the financial manager thinks in terms of value. Not in cost or profit. In value.

And that changes everything.

Because value encompasses all the financial consequences of decisions, in the short, medium and long term. The financial manager is not there to make a quick deal as a trader would. The long-term consequences of the decisions she takes today do not normally leave her indifferent, because they have an immediate impact on value. This is an impact that can be mitigated by the mechanics of discounting, but an impact nonetheless.

The financial manager, by joining a company, does not abandon her status as a citizen. To each their role and responsibilities however. In today’s environment, the role of the State is to encourage companies, through regulations and taxation, to adopt virtuous behaviour in terms of ecological transition, social responsibility and sustainability. The role of the company is to adapt its strategy, processes and procedures in order to follow that road. The role of the financial manager is to ensure that the commitments made in these and other areas are respected.

It goes without saying that a company may voluntarily be a leader in these areas and do more than is required by regulations. For example, L’Oréal guarantees all its employees worldwide the same level of social protection as in France. And that makes a big difference for Indonesians and Nigerians! But a company still needs to have the economic means to offer this. Today, it is the companies that create value that can afford these types of employment conditions. With the crisis that erupted mid-2020 we will see how many groups still have the resources to implement these voluntary policies.

In the long term, we can imagine that this relationship may be reversed and that it will no longer be possible to create value without first being virtuous, as the majority of consumers, human talent and investors will no longer want to deal with companies that do not respect the environment and are not aware of their social responsibilities. It is no secret, though, that many new editions of the Vernimmen will be published before this becomes a reality.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISE

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

Chapter 27. MEASURING VALUE CREATION

Chapter 27

MEASURING VALUE CREATION

Separating the wheat from the chaff

Creating value has become such an important issue in finance that a host of indicators have been developed to measure it. They come under a confusing array of acronyms – TSR, MVA, EVA, CFROI, ROCE, WACC – but most of these will probably be winnowed out in the years to come. Ultimately, they should be reduced to those few that best mirror and address the recent developments in cash flow statements.

The current profusion of indicators has its advantages, as normally we expect only the most reliable to survive. However, in practice some companies use the lack of clear guidelines and standards to choose indicators that best serve their interests at a given time, even if this involves the laborious task of changing indicators on a routine basis.

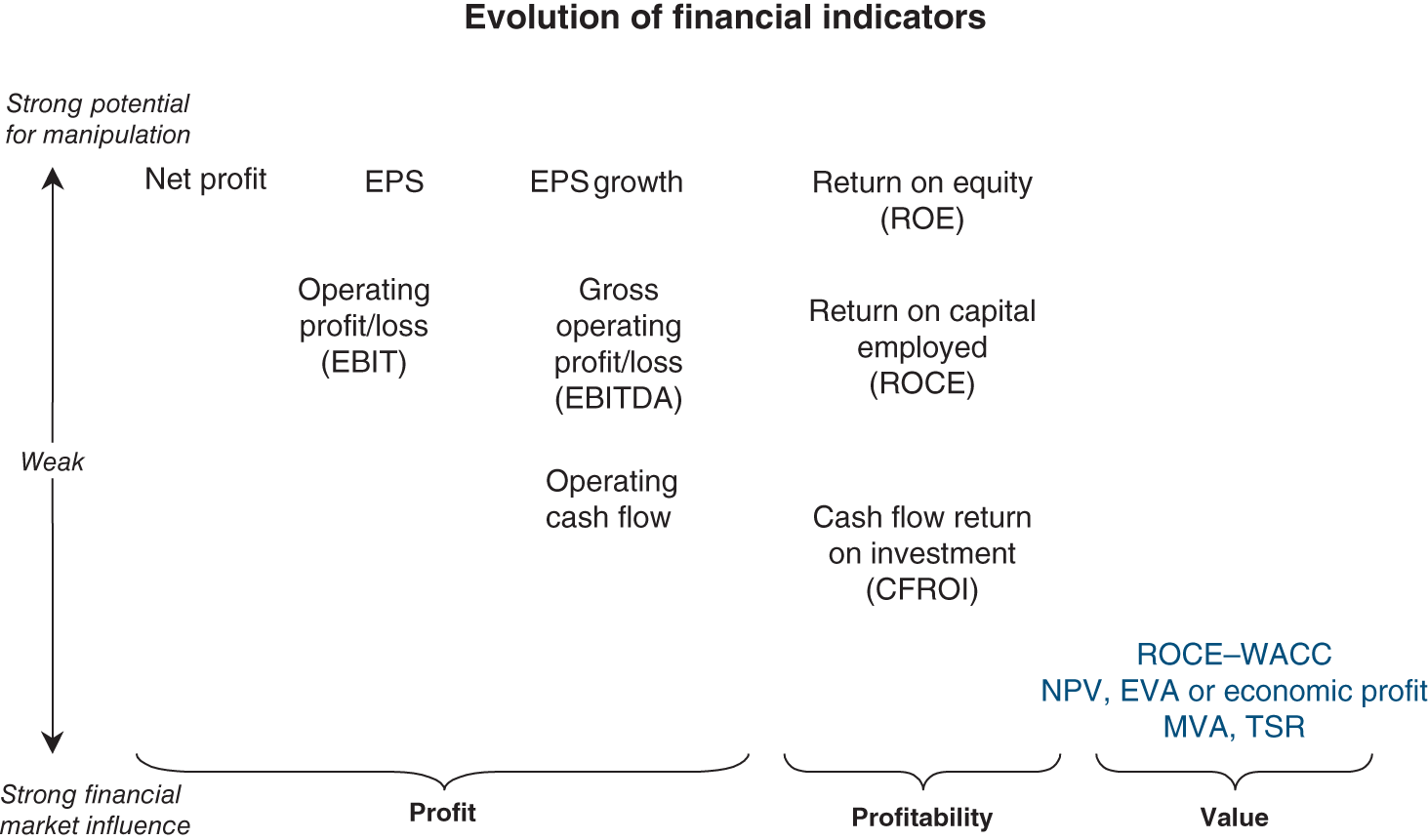

The chart below should help you find your way through the maze of indicators. It plots value creation measures according to three criteria: ease of manipulation, sensitivity to financial markets and category (accounting, economic or stock market indicators).

Section 27.1 OVERVIEW OF THE DIFFERENT CRITERIA

Value creation indicators fall into four categories:

- Accounting indicators. Until the mid-1980s, companies mainly communicated their net profit/loss or earnings per share (EPS). Regrettably, this is a key accounting parameter that is also very easy to manipulate. This practice of massaging EPS is called “window dressing”, or improving the presentation of the accounts by adjusting exceptional items, provisions, etc. The growing emphasis on operating profit or EBITDA represents an improvement because it considerably reduces the impact of exceptional items and non-cash expenses. It is regrettable that the IASB has refused to define EBITDA, which leaves companies free to choose their own definition, whereas for us there is only one: the difference between all operating revenues and expenses that sooner or later results in a cash inflow or outflow; and which has eliminated exceptional items that are now included in the various expense items.

The second-generation accounting indicators appeared as investors began to reason in terms of profitability, i.e. efficiency, by comparing return with the equity used. One such ratio is called return on equity (ROE). However, it is possible to leverage this value as well, since a company can boost its ROE by skilfully raising its debt level. Even though ROE might look more attractive, no “real” value has been created since the increased profitability is cancelled out by higher risk not reflected in accounting data.

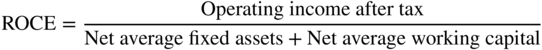

Since the return on capital employed (ROCE) indicator avoids this bias, it has tended to become the main measure of economic performance. Only in a few sectors of activity is it meaningless to use ROCE (essentially in banking or insurance, where ROE is widely used).

These rates mainly fall into the field of accounting, rather than finance.

While NPV and other economic indicators represent valuable tools for strategic analysis and a good basis for estimating the market value of companies, they are based on projections that are frequently difficult to assess. Unfortunately, the cash flow for one single year is easy to manipulate and meaningless. Indeed, it is not intuitively interpretable. At the same time, we know that the major drivers of cash flows are the growth of earnings and revenues of the company and ROCE. By focusing attention on ROCE, there is a better intuitive grasp of how the company is performing. It is then easier to assess the firm’s growth, both over time and relative to its industry.

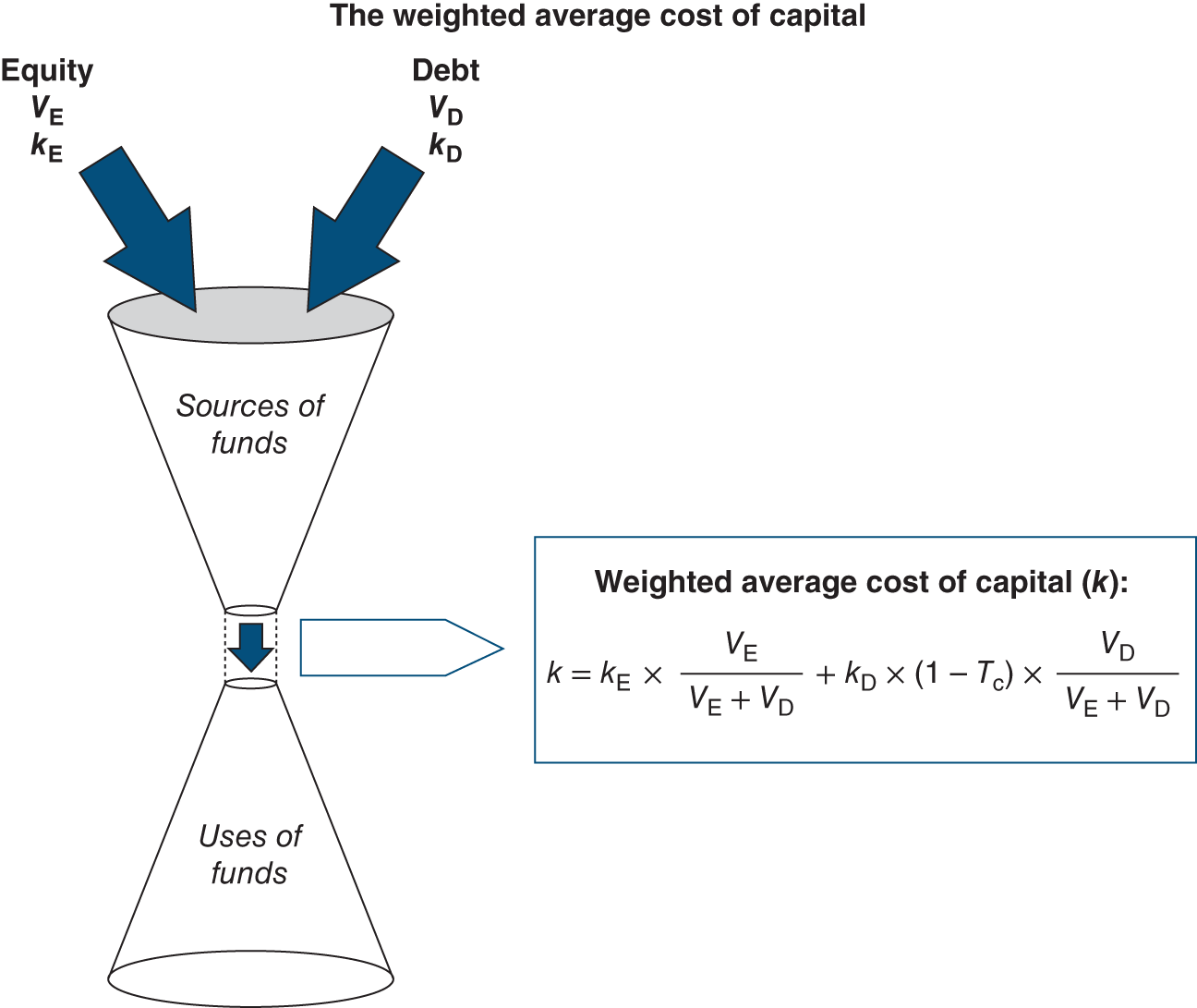

- Accounting/financial indicators emerged with the realisation that profitability per se cannot fully measure value because it does not factor in risks. To measure value, returns must also be compared with the cost of capital employed. Using the cost of financing a company, called the weighted average cost of capital, or WACC,1 it is possible to assess whether value has been created (i.e. when return on capital employed is higher than the cost of capital employed) or destroyed (i.e. when return on capital employed is lower than the cost of capital employed).

But companies can also go one step further by applying the calculation to capital employed at the beginning of the year in order to measure the value created over the period. The difference can then be expressed in currency units rather than as a percentage. This popular measure of value creation has been most notably developed in the EVA, or economic value added, model. It is also known as economic profit.

These indicators are mainly used for decentralised management control and for the calculation of variable compensation, often linked directly or indirectly to economic profit.

- Financial indicators. Yet the best of all indicators is undoubtedly net present value (NPV, see Chapter 16), which provides the exact measure of value created. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that intrinsic value creation is the principal driver of companies’ market value. But NPV has one drawback because it must be computed over several periods. For the external analyst who does not have access to all the necessary information, the NPV criterion becomes difficult to handle. The quick and easy solution is to use the above-mentioned ratios. It is important to remember that while the other ratios are simpler to use, they are also less precise and may prove misleading when not used with care.

They are mostly used for investment choices and valuation.

- Market indicators: market value added (MVA) and total shareholder return (TSR) are highly sensitive to the stock market. MVA represents the difference on the one hand between the value of equity and net debt, and on the other the book value of capital employed. It is expressed in currency units. TSR is expressed as a percentage and corresponds to the addition of the dividend yield on the share (dividends/value of the share) and the capital gains rate (capital gains during the period divided by the initial share value). It is the return earned by a shareholder who bought the share at the beginning of a period, earned dividends and then sold the share at the end of the period.

A major weakness with these two measures is that they may show destruction in value because of declining investor expectations about future profits, even though the company’s return on capital employed is higher than its cost of capital. This is the case for Bic, which has seen its share price drop since 2015, despite having an average ROCE above 12% every year since then, for a cost of capital of roughly 7%. Conversely, in a bull market, a company with mediocre economic performance may have flattering TSR and MVA. In the long term, these highs and lows are smoothed out and TSR and MVA would eventually reflect the company’s modest performance. Yet in the meantime, there may be some major divergences between these indicators and company performance.

TSR is sometimes used as an index for variable compensations. MVA is rarely used.

A clear distinction must be made between economic indicators and measures of stock market value creation (TSR and MVA). The former measure the past year’s performance, while the latter tend to reflect anticipation of future value creation. The measures of stock market value creation take into account the share price, which reflects this anticipation. Yet the different measures of economic performance and stock market value are complementary, rather than contradictory.

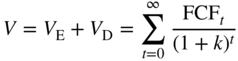

Section 27.2 NPV, THE ONLY RELIABLE CRITERION

It should now be clear that the concept of value corresponds perfectly to the measure of NPV. Financial management consists of constantly measuring the net present value of an investment, project, company or source of financing. Obviously, one should only allocate resources if the net present value is positive; in other words, if the market value is lower than the present value. Net present value reflects how allocation of the company’s resources has led to the creation or destruction of value. On the one hand, there is a constant search for anticipated financial flows – while keeping in mind the uncertainty of these forecasts. On the other hand, it is necessary to consider the rate of return (k) required by the investors and shareholders providing the funds.

The value created is thus equal to the difference between the capital employed and its book value. Book value is the amount of funds invested in the company’s operations.

The creation of value reflects investors’ expectations. Typically, this means that, over a certain period, the company will enjoy a rent with a present value allowing its capital employed to be worth more than its book value!

While NPV is widely used within companies to make investment choices (Chapter 28), it is hardly ever used by the company in its external communication on its value creation.

If it were to do so, it would be obliged to give precise details of its business plan and future cash flows to the public. No company is prepared to do so in order not to give confidential information to its competitors, nor to give the impression of making performance commitments that it might not keep because it is dependent on economic and financial conditions that are beyond its control.

Hence the development of value creation indicators, which are much less indiscreet, but also often much less effective and much easier to manipulate!

Section 27.3 FINANCIAL/ACCOUNTING CRITERIA

1/ ECONOMIC PROFIT OR EVA

Economic profit is less ambitious than net present value. It only seeks to measure the wealth created by the company in each financial year. EVA does not just factor in the cost of debt, such as in calculating net profit, but also accounts for the cost of equity.

Economic profit or EVA first measures the excess of ROCE over the weighted average cost of capital. Then, to determine the value created during the period, the ratio is multiplied by the book value of thecapital employed at the start of the reporting period. Thus, a company that had an opening book value of capital employed of 100 and an after-tax return on capital employed of 12% with a WACC of only 10% will have earned 2% more than the required rate. It will have created a value of 2 on funds of 100 during the period.

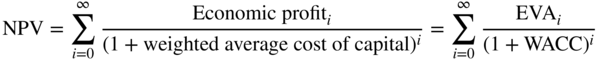

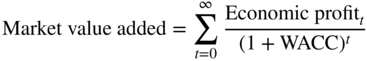

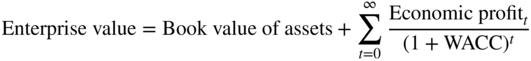

Economic profit is related to net present value, because NPV is the sum of the economic profits discounted at the weighted average cost of capital:

The table shows EVA for some European firms.

| Company | 2020 EVA (€m) | Company | 2020 EVA (€m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roche | 12,800 | Adidas | (26) |

| Nestlé | 6,912 | Bonduelle | (39) |

| L’Oréal | 2,831 | E.ON | (54) |

| AstraZeneca | 1,164 | Heidelberg Cement | (102) |

| Peugeot | 576 | Michelin | (312) |

| Carrefour | 278 | BASF | (759) |

| RTL | 245 | Shell | (974) |

| Carlsberg | 169 | LafargeHolcim | (1,222) |

| Proximus | 102 | Telecom Italia | (1,913) |

| Criteo | 46 | ArcelorMittal | (2,485) |

| BIC | 14 | ENI | (3,557) |

| Heineken | 0 | Deutsche Telekom | (3,784) |

Source: Data from Exane BNP Paribas, Factset

To calculate EVA, it is necessary to switch from an accounting to an economic reading of the company. This is done by restating certain items of capital employed as follows:

- The exceptional losses of previous years must be restated and added to capital employed insofar as they artificially reduce the company’s capital.

- The goodwill recorded in the balance sheet must be taken as gross, i.e. corrected for cumulative amortisation or impairment, the badwill must be deducted from equity and assets.

- Other major restatements are for deferred tax liabilities and for depreciation (so as to be consistent with capital employed obtained through previously mentioned restatements).

Of course, the profit and loss account (operating profit/loss and taxes) must be restated to ensure consistency with the capital employed calculated previously.

The firms that develop economic profit tools for companies generally have a long list of accounting adjustments that attest to their expertise. Such accounting expertise typically represents a barrier to entry for others seeking to perform the same analyses.

EVA’s novelty also lies in its scope of application, since it enables a company to measure performance at all levels by applying an individual required rate of return to various units. It is a decentralised financial management tool.

A firm may be tempted to maximise short-term EVA, which may be detrimental to future EVAs (underinvestment, artificial reduction of working capital). In general, it is very complex to pick annual criteria that will make it possible to measure value creation for a firm properly. Only the NPV of future cash flows allows us to take into account the long-term capacity to create value.

2/ CASH FLOW RETURN ON INVESTMENT

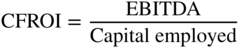

The original version of cash flow return on investment (CFROI) corresponds to the average of the internal rates of return on the company’s existing investments. It measures the IRR earned by a firm’s existing projects.

CFROI is the internal rate of return that equals the company’s gross capital employed, i.e. before depreciation and adjusted for inflation, and the series of after-tax EBITDA computed over the lifetime of existing fixed assets (estimated by dividing the gross value of fixed assets by the depreciation). CFROI is then compared with the weighted average cost of capital. If CFROI is higher than WACC, then the company is creating value; if it is lower, then the firm is destroying value.

As with EVA, computing CFROI requires a number of restatements, which seem to exist mainly to convince their users to hire the founder of the concept (Holt) to implement it. It is sometimes used in a very simplified manner, which makes it very close to a mere accounting criterion (see Section 27.5).

Section 27.4 MARKET CRITERIA

1/ CREATING STOCK MARKET VALUE (MARKET VALUE ADDED)

For listed companies, market value added (MVA) is equal to:

In most cases, if no other information is available, we assume that net debt corresponds to its book value. Thus, the equation becomes simpler:

So, market value added is frequently considered to be the difference between market capitalisation and the book value of equity. This is the equivalent of the price-to-book ratio (PBR) discussed in Chapter 22.2 The table shows MVA for some large listed European companies.

| Company | 2020 MVA (€m) | Company | 2020 MVA (€m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adidas | 53,250 | NRJ | (170) |

| ABB | 36,716 | Peugeot | (533) |

| Sanofi | 36,080 | Heidelberg Cement | (1,124) |

| Deutsche Telekom | 35,286 | Stellantis | (5,268) |

| Ericsson | 23,974 | ENI | (6,594) |

| Cap Gemini | 15,299 | Natixis | (7,845) |

| Total | 8,900 | Orange | (8,502) |

| Michelin | 6,084 | ArcelorMittal | (11,992) |

| Telefonica | 6,056 | Renault | (14,197) |

| Nokia | 5,258 | Vodafone | (17,735) |

| Saint Gobain | 2,084 | NatWest | (20,146) |

| M6 | 616 | Porsche | (27,309) |

| Bonduelle | (12) | Crédit Agricole | (28,315) |

Source: Data from Exane BNP Paribas, Factset.

It is not complex to demonstrate the relationship between market value added and intrinsic value creation in equilibrium markets, since:

Economic profit being equal to capital employed × (ROCE − WACC). This is also equivalent to:

However, those who do not believe in market efficiency contend that MVA is flawed because it is based on market values that are often volatile and out of the management’s control. Yet this volatility is an inescapable fact for all, as that is how the markets function.

2/ TOTAL SHAREHOLDER RETURN (TSR)

TSR is the return received by the shareholder who bought the share at the beginning of a period, earned dividends (which are generally assumed to have been reinvested in new shares) and values their portfolio with the last share price at the end of the period. In other words, TSR equals (share appreciation + dividends)/price at the beginning of the period.

In order for it to be meaningful, the TSR ratio is calculated on a yearly basis over a fairly long period of, say, 5–10 years. This smooths out the impact of erratic market movements, e.g. the tech, media and telecom stock bubble of 2000, the 2007–2010 or the Covid-19 crisis.

By way of illustration, here is the TSR of a few major groups over the last 10 years.

| Company | TSR over 10 years | Company | TSR over 10 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | 30.7% | Rio Tinto | 7.6% |

| L’Oréal | 16.2% | Vinci | 6.3% |

| Allianz | 11.2% | Total | 4.6% |

| Nestlé | 10.5% | ICBC | 3.7% |

| Infosys | 10.2% | IBM | 1.7% |

| Enel | 10.1% | General Electric | –1.3% |

| Sanofi | 9.4% | Vale | –1.6% |

| Toyota | 9.3% | Nokia | –1.8% |

| Siemens | 9.3% | Santander | –5.7% |

| Coca-Cola | 8.3% | Cathay Pacific | –6.5% |

Source: Data from DQYDJ and ycharts

Section 27.5 ACCOUNTING CRITERIA

Certain accounting indicators, like net profit, shareholders’ equity and cash flow from operations, are more representative of a firm’s financial strength. As such they are flawed to measure value creation.

Earnings per share and the accounting rates of return (ROCE, ROE), whilst systematically used as analytical criteria for all financial decisions, even at the board level, are not without faults as they largely ignore risk due to their accounting origin.

It is inappropriate to believe that by artificially boosting them you have created value. Nor is it correct to assume that there is a constant and automatic link between improving these criteria and creating value. In order to maximise value, it is simply not enough to maximise these ratios, even if they are linked by a coefficient to value or the required rate of return.

1/ EARNINGS PER SHARE

Notwithstanding the comments just made about earnings per share, many financial managers continue to favour using it, especially with regard to financial communication. Despite its limitations, it is still the most widespread multiple because it is directly connected to the share price via the price/earnings ratio. EPS’s popularity is rooted in three misconceptions:

- the belief that earnings per share factors in the cost of equity and, therefore, the cost of risk;

- the belief that accounting data influence the value of the company. Changing accounting methods (for inventories, depreciation, goodwill, etc.) will not modify the company’s value, even if it does change earnings per share; and

- the belief that any financial decision that lifts EPS will change value as well. This would imply that the P/E ratio3 remains the same before and after the financial decision, which is frequently not the case. Thus, value is not a direct multiple of earnings per share, because the decision may affect investors’ assessment of the company’s risks and growth potential.

Consider Company A, which, based upon its risks and growth and profitability prospects, has a P/E ratio of 20. Its net profit is 50. Company B has equity of 450 with net profit of 30, giving it a P/E of 15. Company A decides to acquire a controlling interest in Company B, paying a premium of 33% on B’s value, i.e. a total of 600. Company A finances the acquisition entirely by taking on debt at an after-tax cost of 3%. Both Companies A and B are fairly valued. There are no industrial or commercial synergies that could increase the new group’s earnings, and no goodwill.

Company A’s net profit is thus:

Since A financed its acquisition of B entirely through debt, it still has the same number of shares. The increase in earnings per share, also called earnings per share accretion, is therefore equal to that in net profit; that is, +24%. This certainly seems like an extraordinary result!

But has A really created value by buying B?

The answer is no, since there are no synergies to speak of between A and B. Keep in mind that A paid 33% more than B’s equilibrium price. In fact, Company A has destroyed value in proportion to this premium, i.e. 150, because it cannot be offset by synergies.

In fact, the explanation for the – apparent – paradox of a 24% rise in earnings per share matched by a destruction of value is that the buyer’s EPS has increased, because the P/E ratio of the company bought by means of debt is higher than the after-tax cost of the debt. Here, B has a P/E ratio of 20 given the 33% premium paid by A on the acquisition. The inverse of 20 (5%) is much higher than the 3% after-tax cost of the debt for A.

Consider now Company C, which has equity of 1,400 with net profit of 140, i.e. a P/E of 10. It merges with Company D, which has the same risk exposure, equity of 990 and a P/E of 18 (net profit of 55), with no control premium. Thanks to very strong industrial synergies, C is able to boost D’s net profit by 50%. Without doubt, value has been created. And yet, it is not difficult to prove (see Exercise 1) that C’s EPS dropped 7% after the merger. This is a mechanical effect due simply to the fact that D’s P/E of 18 is higher than C’s P/E of 10, because D has better earnings prospects than C.

So, what was the net result of Company C’s acquisition of Company D? The question is not whether Company C’s EPS has been enhanced or diluted, but whether it paid too much for D. In fact, it did not, since there was no control premium paid and industrial synergies were created. After the operation, C’s share will trade at a higher P/E ratio, as it should enjoy greater earnings growth thanks to the contribution from D’s higher-growth businesses. In the end, C’s higher P/E ratio should more than compensate for C’s diluted EPS, lifting the share price. This is only logical considering that the industrial synergies created value.

If these three conditions are met, we can assume that EPS growth reflects the creation of value, and EPS dilution the destruction of value.

If just one of these conditions is lacking, then there is no way to infer that any increase in EPS reflects the creation of value, nor that a decrease is a destruction of value. In our example of a combination between A and B financed by debt, although A’s EPS rose 24%, its risk increased sharply. Its position is no longer directly comparable with that before the acquisition of B.

Similarly, C’s post-merger EPS cannot be compared with its EPS prior to the merger. While the merger did not change its financial structure, C’s growth rate after the merger with D is different from what it was beforehand.

2/ EARNINGS PER SHARE ADJUSTED FOR THE COST OF CARBON EMISSIONS

Used for the first time by Danone in February 2020, this adjusted EPS makes the cost of the carbon footprint visible in financial performance. It measures the accounting enrichment of the shareholder, in relation to one share, once the cost of the carbon credits that the company would have to acquire to offset its greenhouse gas emissions is taken into account. Danone has estimated them on the basis of a cost of €35 per tonne of carbon.

The cost of the externalities that the company causes to the community is thus integrated into the company’s financial performance, thus finally linking the two worlds of finance and non-finance.

At a constant cost of carbon credits, this EPS will grow faster than traditional EPS for companies that reduce their carbon footprint, which should enable investors to value them better. It is simply calculated from the net profit (group share) used to calculate EPS, from which the estimated greenhouse gas emissions multiplied by the price per tonne of carbon is subtracted, before dividing the balance by the number of diluted shares.

Once this calculation has been made, there is no reason why the other value creation indicators presented in this chapter cannot be adjusted in the same way.

It may be that the current EPS adjusted for carbon costs will not ultimately be the criterion retained by the market or the most relevant, but we have to start somewhere … and someone has to start.

3/ ACCOUNTING RATES OF RETURN

Accounting rates of return comprise:

- return on equity (ROE);

- return on capital employed (ROCE), which was described in Chapter 13; and

- cash flow return on investment (CFROI), the simplified version of which compares EBITDA with gross capital employed, i.e. before amortisation and depreciation of fixed assets.

This ratio is used particularly in business sectors wherein charges to depreciation do not necessarily reflect the normal deterioration of fixed assets, e.g. in the hotel business.

The main drawback of accounting rates of return on equity or capital employed is precisely that they are accounting measures. As shall be demonstrated below, these have their dangers.

Consider5 Company X, which produces a single product and generates a return of 20% on capital employed amounting to 100. X operates in a highly profitable sector and is considering external growth opportunities. Should it expect the present 20% rate of return to be generated on other possible projects? If it does, X will never invest because it is unlikely that any other investments will meet these criteria.

How can this problem be rationally approached? The company generates an accounting return of 20%. Suppose its shareholders and investors require a 10% return. Its market value is thus 20 / 10%, or 200.

The proposed investment amounts to 100 and generates a return of 15% on identical risks. The required rate of return is constant at 10%. We see that:

This yields an enterprise value of 35 / 10% = 350 (+150), with a return on capital employed of 35 / 200 = 17.5%.

The value of the capital employed has increased by more than the amount invested (150 vs. 100), because the profitability of Company X’s investment (15%) is higher than the rate required by its shareholders and investors (10%). Value has been created, and X was right to invest. And yet, the return on capital employed fell by 20% to 17.5%, demonstrating that this criterion is not relevant.

The inverse example is Company Y, which has a return of 5% on capital employed of 100. Assuming the shareholders and investors require a 10% return as well, the value of Y’s capital employed is 5 / 10% = 50.

The proposed investment amounts to 25 and yields a return of 8%. Since we have the same 10% required return, we get:

This results in capital employed being valued at 7 / 10% = 70 (+20), with a return of 7 / 125 = 5.6%.

The value of Y’s capital employed has indeed increased by 20, but this is still less than the increase of 25 in capital invested. Value has been destroyed. The return on the investment is just 8%, whereas the required rate is 10%. The company has lost money and should not have made the investment. And yet the return on capital employed rose from 5% to 5.6%.

Similarly following an acquisition financed with a share issue, one could demonstrate that ROE increases when the target company’s reverse 1 / (P/E) is higher than the buyer’s current ROE.

Setting aside all these accounting concepts, to focus on financial concepts, such as requested rates of return (k).

Unfortunately, some corporate managers continue to view decision-making in terms of the impact on accounting measures (EPS and accounting profitability), even though it has just been demonstrated that these criteria have little to say about the creation of value. True, accounting systems are a company’s main source of information. However, financial managers need to focus first and foremost on how financial decisions affect value.

Let’s discuss synergy effects before mentioning EPS accretion!

Section 27.6 SYNTHESIS

As long as performance measures and their implementation remain so diversified, it is vital to have a good understanding of their respective flaws. By choosing one or another measure, companies can present their results in a more or less flattering light. Financial managers typically choose those measures that will demonstrate the creation, rather than the destruction, of value.

| Financial criteria | Financial/accounting criteria | Accounting criteria | Market criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | Net present value | Economic profit | Cash flow return on investment | Earnings per share | Accounting rates of return | Market value added | Total shareholder return | |

| Acronym | NPV | EVA | CFROI | EPS | ROE, ROCE | MVA | TSR | |

| Strengths | The best criterion | Simple indicator leading to the concept of weighted average cost of capital | Not restricted to just one year | Historical data; simple | Simple concepts | Astoundingly simple; reflects total rather than annual value created | Represents shareholder return in the medium to long term | |

| Weaknesses | Difficult to calculate for an external analyst | Restricted to one year; difficult to evaluate changes over a period of time | Complex calculations | Does not factor in risks; easily manipulated; does not factor in the cost of equity | Accounting measures, thus do not factor in risks; restricted to one year; to be significant, must be compared with the required rate of return | Subject to market volatility; difficult to apply to unlisted companies | Calculated over too short a period; subject to market volatility | |

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 See Chapter 29. Cost of capital is the weighted average cost of financial resources (equity and debt) available for the firm. It is therefore the minimum return that the company shall provide in order to satisfy the fund providers and hence create value.

- 2 The market-to-capital ratio is a variation of MVA expressed as a ratio rather than a unit amount, because it is obtained by dividing the market capitalisation of debt and equity by the amount of capital invested.

- 3 The P/E ratio is equal to price/earnings per share. It measures the relative expense of a share.

- 4 Before goodwill accounting.

- 5 To simplify the discount calculation, we assume that the planned investments will generate a return to infinity.

Chapter 28. INVESTMENT CRITERIA

Chapter 28

INVESTMENT CRITERIA

Back to flows and financial analysis

The “mathematics” we studied in Chapters 16 and 17, dealing with present value and internal rate of return, can also be applied to investment decisions and financial securities. These theories will not be covered again in detail, since the only real novelty is of a semantic nature. In the sections on financial securities, we calculated the yield to maturity. The same approach holds for analysing industrial investments, whereby we calculate a rate that takes the present value to zero. This is called the internal rate of return (IRR). Internal rate of return and yield to maturity are thus the same.

This chapter will discuss:

- the cash flows to be factored into investment decisions, which are called incremental cash flows; and

- other investment criteria, which are less relevant than NPV and IRR and have proven disappointing in the past. As financial managers, you should nevertheless be aware of them, even if they are more pertinent to accounting work than financial management: payback period, accounting rate of return, profitability indicator.

Section 28.1 THE PREDOMINANCE OF NPV AND THE IMPORTANCE OF IRR

Each investment has a net present value (NPV), which is equal to the amount of value created. Remember that the net present value of an investment is the value of the positive and negative cash flows arising from an investment, discounted at the rate of return required by the market. The rate of return is based upon the investment’s risk.

From a financial standpoint, and if forecasts are correct, an investment with positive NPV is worth making since it will create value. Conversely, an investment with negative NPV should be avoided as it will destroy value.

Sometimes investments with negative NPV are made for strategic reasons, such as to protect a position in the industry sector or to open up new markets with strong, yet hard-to-quantify, growth potential. It must be kept in mind that if the NPV is really negative, it will certainly lead to the destruction of value. Sooner or later, projects with negative NPV have to be offset by other investments with positive NPV that create value. Without doing so, the company will be headed for ruin.

The internal rate of return (IRR) is simply the rate of return on an investment. Given an investment’s degree of risk, it is financially worthwhile if the IRR is higher than the required return. On the other hand, if the IRR is lower than the risk-based required rate of return, the investment will serve no financial purpose.

Net present value (NPV) measures the value created by the investment and is the best criterion for selecting or rejecting an investment, whether it is industrial or financial. When it is simply a matter of deciding whether or not to make an investment, NPV and IRR produce the same outcome. However, if the choice is between two mutually exclusive investments, net present value is more reliable than the internal rate of return.

From a conceptual and methodological point of view, NPV is a better criterion as it takes into account risk (payback ratio does not), the whole stream of cash flows (idem) and assumes that intermediate cash flows are reinvested at the cost of capital, which is more realistic than IRR (which implicitly assumes reinvestment at the IRR, which may be above the cost of capital).

Actual computation of NPV is not always well applied. Indeed, some managers discount cash flows using the cost of capital of the group and not at a rate that reflects the market risk of the specific project. It should be kept in mind that a very risky project will increase the overall risk of the firm and thus should be discounted at a higher rate (and vice versa). We will highlight this point in the next chapter.

Graham and Harvey (May 2001) conducted a broad survey of corporate and financial managers to determine which tools and criteria they use when making financial decisions. They asked them to indicate how frequently they used several capital budgeting methods. The findings showed that net present value and internal rate of return carry the greatest weight, and justifiably so. Some 75% of financial managers systematically value investments according to these two criteria. This proportion increases over time demonstrating that pedagogy in finance is not useless.

Interestingly, large firms apply these criteria more often than small and medium-sized companies, and MBA graduates use them systematically while older managers tend to rely on the payback ratio.

Conclusions are slightly different for small and medium companies for which (according to a study by Danielson and Scott) intuition comes first (26%), then payback ratio (19%), ROCE (14%) and NPV (12%).

Section 28.2 THE MAIN LINES OF REASONING

All investment decisions must comply with the following six principles:

- consider cash flows rather than accounting data;

- reason in terms of incremental cash flows, considering only those associated with the project;

- reason in terms of opportunity;

- disregard the type of financing;

- consider taxation; and

- above all, be consistent.

1/ REASON IN TERMS OF CASH FLOWS

We have already seen that the return on an investment is assessed in terms of the resulting cash flows. Indeed, only cash flows can be invested and earn interest or be used to repay a debt and stop the payment of its interests. One must therefore analyse the negative and positive cash flows, and not the accounting income and expenses. These accounting measures are irrelevant because they do not take into account working capital generated by the investment and include depreciation, which is a non-cash item.

We stress the fact that in finance, an amount costs only when it is disbursed and earns only when it is received, regardless of the accounting treatment applied to it.

2/ REASON IN TERMS OF INCREMENTAL FLOWS

When considering an investment, one must take into account the flows it generates, all the flows derived from the investment, and nothing else but these flows. It is crucial to assess all the consequences of an investment upon a company’s cash position. Some of these are self-evident and easy to measure, and others are less so.

A movie theatre group plans to launch a new complex, and substantial costs have already been incurred in its design. Should these be included in the investment’s cash flows? The answer is no, since the costs have already been incurred regardless of whether or not the complex is actually built. These are sunk costs. Therefore, they should not be considered part of the investment expenditure.

It would be absurd to carry out an investment simply because the preparations were costly and one hopes to recoup funds that, in any case, have already been spent. The only valid reason for pursuing an investment is that it is likely to create value.

Now, if the personnel department has to administer an additional 20 employees hired for the new complex (e.g. 5% of its total workforce), should 5% of the department’s costs be allocated to the new project? Again, the answer is no. With or without the new complex, the personnel department is part of overhead costs. As a general rule, structural costs cannot be attributed, even in part, to an investment because they are independent of it. Structural expenses would only be affected if the planned investment generates additional costs – which in our example is recruitment expenses.

However, design and overheads will be priced (to the extent possible given the competitive environment) into the ticket charged for entry to the new complex. Finance here differs quite markedly from management control.

A perfume company is about to launch a new product line that may cut sales of its existing perfumes by half. Should this decline be factored into the calculation of the investment’s return? Yes, because the new product line will prompt a shift in consumer behaviour: the decline in cash flow from the older perfume stems directly from the introduction of this new product.

Nevertheless, we can mention that in certain very specific sectors with very low marginal costs, this reasoning may lead to overinvestment, creating overcapacity and therefore price wars.

3/ REASON IN TERMS OF OPPORTUNITY

For financial managers, an asset’s value is its market value, which is the price at which it can be bought (investment decision) or sold (divestment decision). From this standpoint, its book or historic value is of no interest whatsoever, except for tax purposes (taxes payable on book capital gains, tax credit on capital losses, etc.).

For example, if a project is carried out on company land that was previously unused, the land’s after-tax resale value must be considered when valuing the investment. After all, in principle, the company can choose between selling the land and booking the after-tax sales price, or using the land for the new project. Note that the book value of the land does not enter into this line of reasoning.

The opportunity principle boils down to some very simple rules:

- if a company decides to hold on to a business, this implies that it should be prepared to buy that business (if it did not already own it) in identical operating circumstances; and

- if a company decides to hold on to a financial security that is trading at a given price, this security is identical to one that it should be prepared to buy (if it did not already own it) at the same price.

Financial managers are, in effect, “asset dealers”. They must introduce this approach within their company, even if it means standing up to other managers who view their respective business operations as essential and viable. Only by systematically confronting these two viewpoints can a company balance its decision-making and management processes.

Theoretically, a financial manager does not view any activity as essential, regardless of whether it is one of the company’s core businesses or a potential new venture. The CFO must constantly be prepared to question each activity and reason in terms of:

- buying and selling assets; and

- entering or withdrawing from an economic sector of activity.

The concept of necessity should be interpreted as regards the strategy of the firm, the investment is then a tool for achieving this strategy; a necessary tool, hence highly profitable.

4/ DISREGARD THE TYPE OF FINANCING