**Section IV. CORPORATE FINANCIAL POLICIES

****PART ONE. CAPITAL STRUCTURE POLICIES

Chapter 32. CAPITAL STRUCTURE AND THE THEORY OF PERFECT CAPITAL MARKETS

Does paradise exist in the world of finance?

The central question of this chapter (and of the following one) is: is there an optimal capital structure? That is to say, is there a “right” combination of equity and debt that allows us to reduce the weighted average cost of capital and therefore to maximise the value of capital employed (enterprise value)?

The reader may be surprised by this question when Chapter 13 showed clearly how return on equity could benefit from the leverage effect. But we have now left the world of accounting in order to enter the universe of finance. Indeed, if we jumped straight to the conclusion, this part of the book could be renamed “the uselessness of the leverage effect in finance”!

Note that we consider the weighted average cost of capital (or cost of capital), denoted k, to be the rate of return required by all the company’s investors either to buy or to hold its securities. It is the company’s cost of financing and the minimum return its investments must generate in the medium term. If not, the company is heading for ruin.

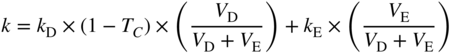

kD is the rate of return required by the lenders of a given company, kE is the cost of equity required by the company’s shareholders, and k is the weighted average rate of the two types of financing, equity and net debt (from now on often referred to simply as debt). The weighting reflects the breakdown of the value of equity and the value of debt in enterprise value.

With VD the market value of net debt and VE the market value of equity, we get:

or, since the enterprise value is equal to the value of net debt plus equity (EV = V = VE + VD):

If, for example, the rate of return required by the company’s creditors is 4%, the corporate tax rate is 25%, the rate of return required by the shareholders is 10% and the value of debt is equal to that of equity, then the return required by all of the company’s sources of funding will be 6.5%.1 Its weighted average cost of capital is thus 6.5%.

To simplify our calculations and demonstrations in this chapter, we shall assume infinite durations for all debt and investments. This enables us to apply perpetual bond analytics and to assume that the company’s capital structure remains unchanged during the life of the project, income being distributed in full. The assumption of an infinite horizon is just a convention designed to simplify our calculations and demonstrations, but they remain accurate even with more realistic hypotheses.

Section 32.1 THE ENTERPRISE VALUE

While accounting looks at a company by examining its past and focusing on its costs, finance is mainly a projection of the company into the future. Finance reflects not only risk but also – and above all – the value that results from the perception of risk and future returns.

From now on, we will speak constantly of value. As we saw previously, by value we mean the present value of future cash flows discounted at the rate of return required by investors:

- equity (E) will be replaced by the value of equity (VE);

- net debt (D) will be replaced by the value of net debt (VD);

- capital employed (CE) will be replaced by enterprise value (EV), or firm value.

As operating assets are financed by equity and net debt (which are accounting concepts), logically, a company’s enterprise value will consist of the market value of net debt and the market value of equity (which are financial concepts). This chapter therefore reasons in terms of:

| Enterprise value or firm value (EV) | Value of net debt (VD) |

| Equity value (VE) |

Important: Enterprise value is sometimes confused with equity value. Equity value is the enterprise value remaining for shareholders after creditors have been paid. To avoid confusion, remember that enterprise value is the sum of equity value and net debt value.

Similarly, we will reason not in terms of return on equity, but rather required rate of return, which was discussed in depth in Chapter 19. In other words, the accounting notions of ROCE (return on capital employed), ROE (return on equity) and i (cost of debt), which are based on past observations, will give way to WACC or k (required rate of return on capital employed), kE(required rate of return on equity) and kD(required rate of return on net debt), which are the returns required by those investors who are financing the company and who hope to get them.

Section 32.2 DEBT AND EQUITY

The fundamental differences between debt and equity should now be crystal clear.

- Debt:

- provides a return for the investor that is independent of the performance of the firm. Except in extreme cases (default, bankruptcy), the lender will earn the interest due (no more, no less) regardless of whether the earnings of the company are excellent, average or bad;

- always has a term, even if remote in time, that is defined contractually. We will not consider for the time being the extremely rare cases of perpetual debts (which are usually only named so when you analyse them more carefully) or a bit more frequent debt with undetermined term;

- is repaid in priority to equity in case of liquidation of the company – the proceeds of the sale of assets will primarily go to lenders, and only if and when lenders have been fully repaid will shareholders receive cash.

- Equity:

- yields returns depending on the profitability of the company. Dividends and capital gains will be nil if the results are not good on a long-term basis;

- does not benefit from a repayment commitment. The only exit for equity can be found by selling to a new shareholder, which will take over the role from the previous one;

- in case of bankruptcy is repaid only after all creditors have been fully repaid. Our readers probably know that in most cases the proceeds from liquidation are not sufficient to repay 100% of creditors. Shareholders are then left with nothing as the company is insolvent.

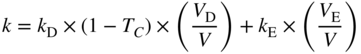

Shareholders fully run the risk of the firm as the cash flows generated by the capital employed (free cash flows to the firm) will first be allocated to lenders; only when they have collected what is due will shareholders be entitled to the remainder.

Given these elements, it becomes natural that the voting rights and therefore the right to choose management lies in the hands of shareholders. Voting rights are only a logical consequence of the first three differences. Shareholders, second to lenders in the collection of cash flows generated by capital employed, run greater risks than the lenders. Lenders are willing to entrust shareholders with power within the company, especially the power to choose the management through voting rights, because they know that it is in the shareholders’ interest to manage the company optimally to maximise its cash flows over time, since the shareholders will only receive a share if the cash flows are sufficient to ensure that the lenders receive what is owed to them first.

The higher the enterprise value, the higher also the equity value. As debt does not run the risk of the firm (except in case of financial distress), its value will largely be independent of the changes in enterprise value. We find here again the concept of leverage, as a small change in enterprise value can have a large impact on equity value.

It should be noted that these two graphs are not on the same scale (the first one on annual cash flows, the second one on values).

Section 32.3 WHAT OUR GREAT-GRANDPARENTS THOUGHT

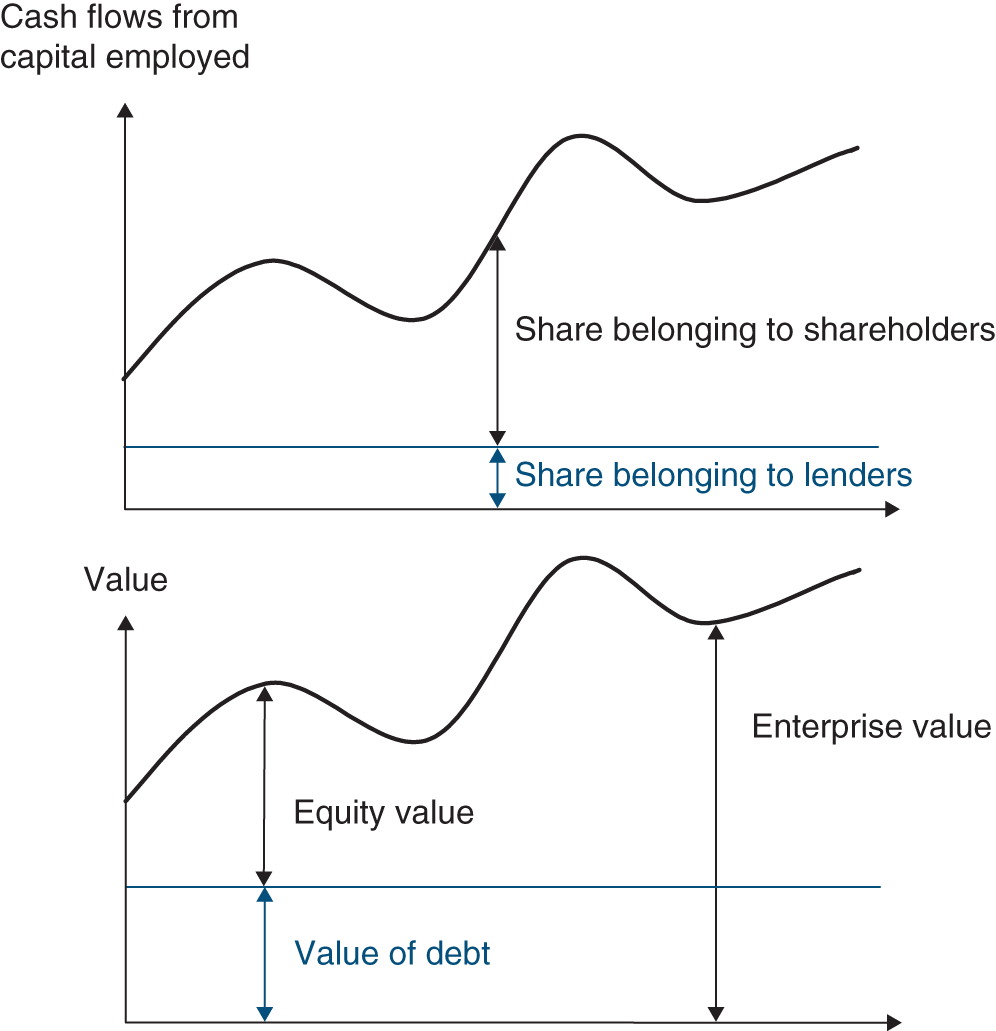

We shall start by assuming a tax-free environment, both for the company and the investor, in which neither income nor capital gains are taxed. In other words, an illusionary heaven! Concretely, the optimal capital structure is one that minimises k, i.e. that maximises the enterprise value (V). Remember that the enterprise value results from discounting free cash flow at rate k. However, free cash flow is not related to the type of financing. The demonstrations below endeavour to measure and explain changes in k according to the company’s capital structure.

We know that ex-ante debt is always cheaper than equity (kD < kE) because it is less risky. Consequently, a moderate increase in debt will help reduce k, since a more expensive resource (equity) is being replaced by a cheaper one (debt). This is the practical application of the preceding formula and the use of leverage.

However, any increase in debt also increases the risk for the shareholder. Markets then demand a higher kE, the more debt we add in the capital structure. The increase in the expected rate of return on equity cancels out part of the decrease in cost arising on the recourse to debt. The higher the relative share of debt, the greater the risk to shareholders and the more shareholders demand a high rate of return on equity, to the point of cancelling out the positive effect of the use of debt.

At this level of financial leverage the company has achieved the optimal capital structure, ensuring the lowest weighted average cost of capital and thus the highest enterprise value. Should the company continue to take on debt, the resulting gains would no longer offset the higher return required by shareholders.

Moreover, the cost of debt increases after a certain level because it becomes more risky. At this point, not only has the company’s cost of equity increased, but also that of its debt.

In this example, the debt-to-equity ratio that minimises k is 0.45. The optimal capital structure is thus achieved with 45% debt financing and 55% equity financing.

Section 32.4 THE CAPITAL STRUCTURE POLICY IN PERFECT FINANCIAL MARKETS

We shall demonstrate this proposition by means of an example given by Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller (1958), who showed that, in a perfect market and without taxes, the traditional approach is wrong. If there is no optimal capital structure, then the overall cost of equity (k or WACC) remains the same regardless of the firm’s debt policy.

The main assumptions behind the theorem are:

- companies can issue only two types of securities: risk-free debt and equity;

- financial markets are frictionless;

- there is no corporate and personal taxation;

- there are no transaction costs;

- firms cannot go bankrupt;

- insiders and outsiders have the same set of information.

According to Modigliani and Miller, investors can take on debt just like companies. So, in a perfect market, they have no reason to pay companies to do something they can handle themselves at no cost.

Imagine two companies that are completely identical except for their capital structure. The value of their respective debt and equity differs, but the sum of both, i.e. the enterprise value of each company, is the same. If the reverse were true, equilibrium would be restored by arbitrage.

We shall demonstrate this using the examples of Companies X and Y, which are identical except that X is unlevered and Y carries debt of 80,000 at 5%. If the traditional approach were correct, Y’s weighted average cost of capital would be lower than that of X and its enterprise value higher. This can be seen in the following table:

Y’s cost of equity (12%) is higher than that of X (10%), since Y’s shareholders bear both the operating risk and that of the capital structure (debt), whereas X’s shareholders incur only the same operating risk. As a matter of fact, the operating risk of X is the same as that of Y, as X and Y are identical but for their capital structures.

Modigliani and Miller demonstrated that Y’s shareholders can achieve a higher return on their investment by buying shares of X, at no greater risk.

Thus, if a shareholder holding 1% of Y shares (equal to 1,333) wants to obtain a better return on their investment, they must:

- sell their Y shares for 1,333…

- … replicate Y’s debt/equity structure by borrowing money for 60% of the equity value, in proportion to their 1% stake; that is, borrow 1,333 × 60% = 800, at 5% …

- … invest all this (800 + 1,333 = 2,133) in X shares.

The shareholder’s risk exposure is the same as before the operation: they are still exposed to operating risk, which is the same on X and Y, as well as to financial risk, since their exposure to Y’s debt has been transferred to their personal borrowing for the same amount (1% of 80,000 or 800). The situations are therefore financially equivalent. Previously, the shareholder of Y was not indebted in their personal capacity and was a shareholder of a company Y with a financial leverage of 60%. Now they have a personal leverage of 60% (800 / 1,333) but is a shareholder of a company X without debt.

Formerly, the investor received annual dividends of 160 from Company Y (12% × 1,333 or 1% of 16,000). Now, their net income on the same investment will be:

They are now earning 173 every year instead of the former 160, on the same personal amount invested and with the same level of risk.

Y’s shareholders will thus sell their Y shares to invest in X shares, reducing the value of Y’s equity and increasing that of X. This arbitrage will cease as soon as the enterprise values of the two companies come into line again.

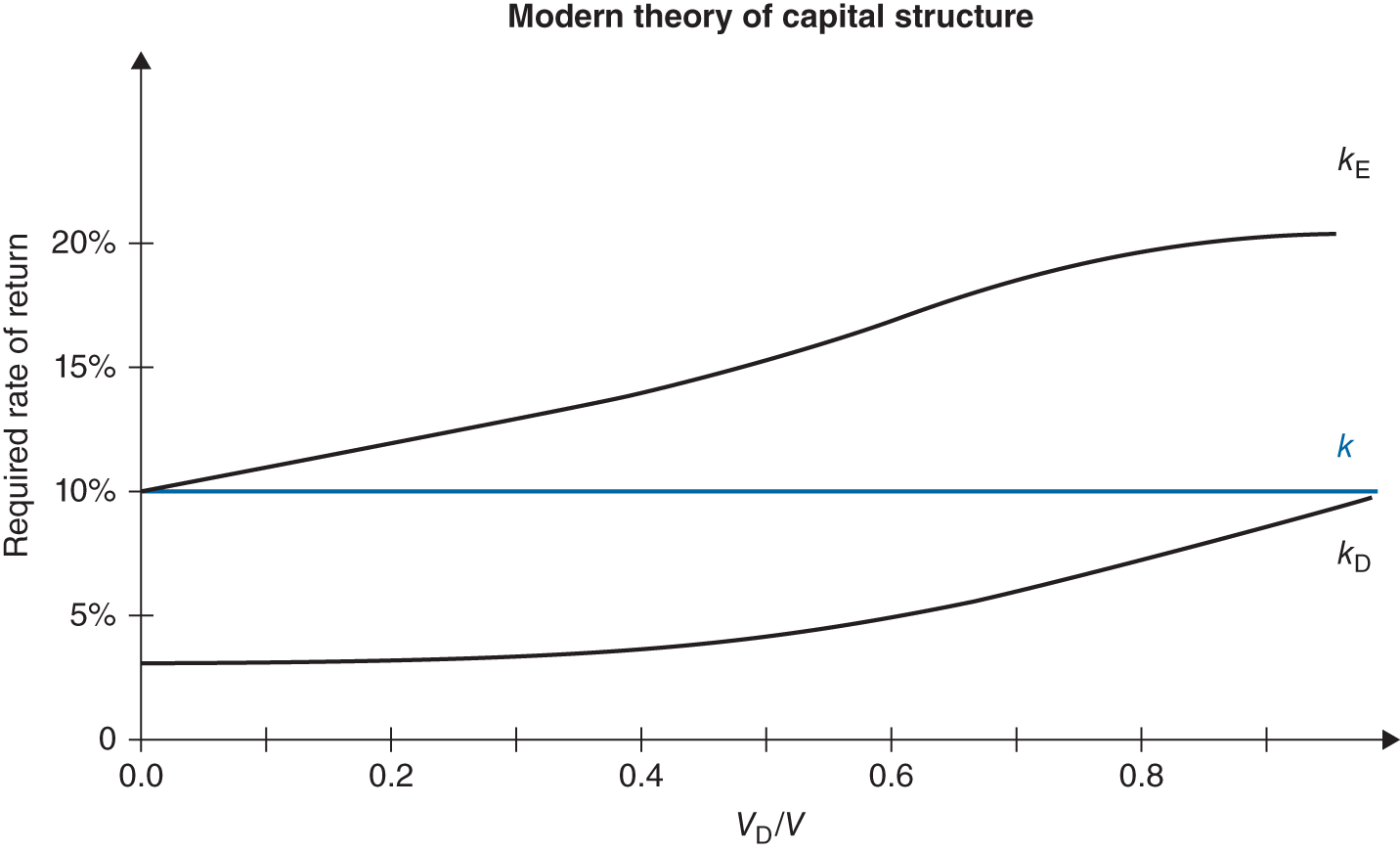

It can be seen that as kD increases, the rate of progression of kE slows down, so that k remains constant.

This relieves the shareholders of part of the company’s risk, which is transferred to the creditors as soon as the amount of the debt becomes significant (see Chapter 34):

| VD/V | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kD | 3% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 3.4% | 3.7% | 4.2% | 5.0% | 6.2% | 7.5% | 8.8% |

| kE | 10% | 10.8% | 11.7% | 12.8% | 14.2% | 15.7% | 17.4% | 18.7% | 19.8% | 20.3% |

| k | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% | 10.0% |

In an efficient market, the increase in expected profitability due to the leverage of debt and the increase in risk offset each other, so that the share value remains the same.

Investing in a leveraged company is neither more expensive nor cheaper than investing in a company without debt; in other words, the investor should not pay twice, first when buying shares at enterprise value and then to reimburse the debt. The value of the debt is deducted from the value of the capital employed to obtain the price paid for the equity.

While obvious, this principle is frequently forgotten. And yet it should be easy to remember: the value of an asset, be it a factory, a painting, a subsidiary or a house, is the same regardless of whether it was financed by debt, equity or a combination of the two. As Merton Miller explained when receiving the Nobel Prize for Economics, “it is the size of the pizza that matters, not how many slices it is cut up into”.

Or, to restate this: the weighted average cost of capital does not depend on the sources of financing. True, it is the weighted average of the rates of return required by the various providers of funds, but this average is independent of its different components, which adjust to any changes in the financial structure. Increasing indebtedness (i.e. a resource with a low cost) seems a priori to lower the cost of capital. But this is forgetting that increasing debt will increase its cost, automatically inducing additional leverage, therefore an increase in risk for shareholders. This increase in the risk that they bear will mechanically translate into an increase in the rate of return that they demand on equity and finally into a constancy of the global company’s cost of financing.

In Chapter 33 we will deepen this analysis by integrating into our reasoning parameters that have been neglected until now (taxation, interests, bankruptcy costs) which will show that the choice of a financial structure is more complicated than what we have just seen, without however calling into question the conclusion of this chapter.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 4% × (1 − 25%) × 50/100 + 10% × 50/100 = 6.5%.

- 2 To simplify calculations, the payout ratio is 100%.

- 3 To simplify calculations, we adopt an infinite horizon with constant flows.

- 4 It is not absurd to think that the interest rate will be the same as before, especially if we speculate that firm X’s shares held by the investor are given to the lending bank as collateral.

Chapter 33. CAPITAL STRUCTURE, TAXES AND ORGANISATION THEORIES

There’s no gain without pain

In the previous chapter we saw that the value of a firm is the same whether or not it has taken on debt. True, shareholders will pay less for the shares of a levered company, but they will have to pay back the debt (or buy it, which amounts to the same thing) before obtaining access to the enterprise value. In the end, they will have paid, directly or indirectly, the same amount (value of equity plus repayment of net debt1); that is, the enterprise value.

Now, what about the financial manager who must issue securities to finance the creation of enterprise value? It does not matter whether they issue only shares or a combination of bonds and shares, since again the proceeds will be the same – the enterprise value.

Enterprise value depends on future flows and how the related, non-diversifiable risks are perceived by the market.

But if that is the case, why diversify sources of financing? The preceding theory is certainly elegant, but it cannot fully explain how things actually work in real life.

In this chapter we look at two basic explanations of real-life happenings. First of all, within the same market logic, biases occur which may explain why companies borrow funds, and why they stop at a certain level. The fundamental factors from which these biases spring are taxes and financial distress costs. Their joint analysis will give birth to the “trade-off model”.

There are features of debt that can modify the optimal capital structure. Trade-off models generally limit their attention to the pros and cons of tax shields and financial distress costs. We believe that the elements of the balance are more numerous than just these factors. Other factors may also be added:

- information asymmetries;

- disciplining role of debt;

- financial flexibility;

- agency costs;

- signalling aspects.

Maybe the main reasons for the interference between capital structure and investment are the divergent interests of the various financial partners regarding value creation and their differing levels of access to information. This lies at the core of the manager/shareholder relationship we shall examine in this chapter. A full chapter (Chapter 34) is devoted to an analysis of the capital structure resulting from a compromise between creditors and shareholders.

Section 33.1 THE BENEFITS OF DEBT OR THE TRADE-OFF MODEL

1/ CORPORATE INCOME TAXES

Up to now, our reasoning was based on a tax-free world, which of course does not exist. The investor’s net return can be two to five times (or more) lower than the pre-tax cash flows of an industrial investment.

It would therefore be foolhardy to ignore taxation, which forces financial managers to devote a considerable amount of their time to tax optimisation.

But we ought not go to the other extreme and concentrate solely on tax variables. All too many decisions based entirely on tax considerations lead to ridiculous outcomes, such as insufficient earnings capacity or a change in fiscal regulations. Tax deficits alone are no reason to buy a company!

In 1963, Modigliani and Miller pushed their initial demonstration further, but this time they factored in corporate income tax (but no other taxes) in an economy in which companies’ financial expenses are tax-deductible, but not dividends. This is pretty much the case in most countries.

The conclusion was unmistakable: once you factor in corporate income tax, there is more incentive to use debt rather than equity financing.

Interest expenses can be deducted from the company’s tax base, so that creditors receive their coupon payments before they have been taxed. Dividends, on the other hand, are not deductible and are paid to shareholders after taxation.

Thus, a debt-free company with equity financing of 100, on which shareholders require a 7.5% return, will have to generate profit of at least 10.4 in order to provide the required return of 7.5 after 28% tax.

If, however, its financing is equally divided between debt at 4% interest and equity, a profit of 9.6 will be enough to satisfy shareholders despite the premium for the greater risk to shares created by the debt (i.e. 11%).

Allowing interest expenses to be deducted from companies’ tax base is a kind of subsidy the state grants to companies with debt. But to benefit from this tax shield, the company must generate a profit.

A company that continually resorts to debt will benefit from tax savings that must be factored into its enterprise value.

Take, for example, a company with an enterprise value of 100, of which 50 is financed by equity and 50 by perpetual debt at 4%. Interest expenses will be 2 each year. Assuming a 28% tax rate and an operating profit of more than 2 regardless of the year under review (an amount sufficient to benefit from the tax savings), the tax savings will be 28% × 2, or 0.56 for each year. The present value of this perpetual bond increases shareholders’ wealth by 0.56 / 14.5% = 3.9 if 14.5% is the cost of equity. Taking the tax savings into account increases the value of equity by 8% to 53.9 (50 + 3.9).

TAX SAVINGS AS A PERCENTAGE OF EQUITY

| Maturity of debt | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VD/V | kE | 5 years | 10 years | Perpetuity | ||

| 0% | 7.5%2 | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||

| 25% | 9.8% | 1% | 2% | 4% | ||

| 33% | 10.9% | 2% | 3% | 5% | ||

| 50% | 14.5% | 4% | 6% | 8% | ||

| 66% | 21.1% | 6% | 9% | 10% | ||

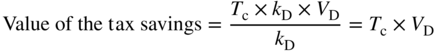

The value of a levered company is equal to what it would be without the debt, plus the amount of savings generated by the tax shield.3

The question now is what discount rate should be applied to the tax savings generated by the deductibility of interest expense? Should we use the cost of debt, as Modigliani and Miller did in their article in 1963, the weighted average cost of capital or the cost of equity?

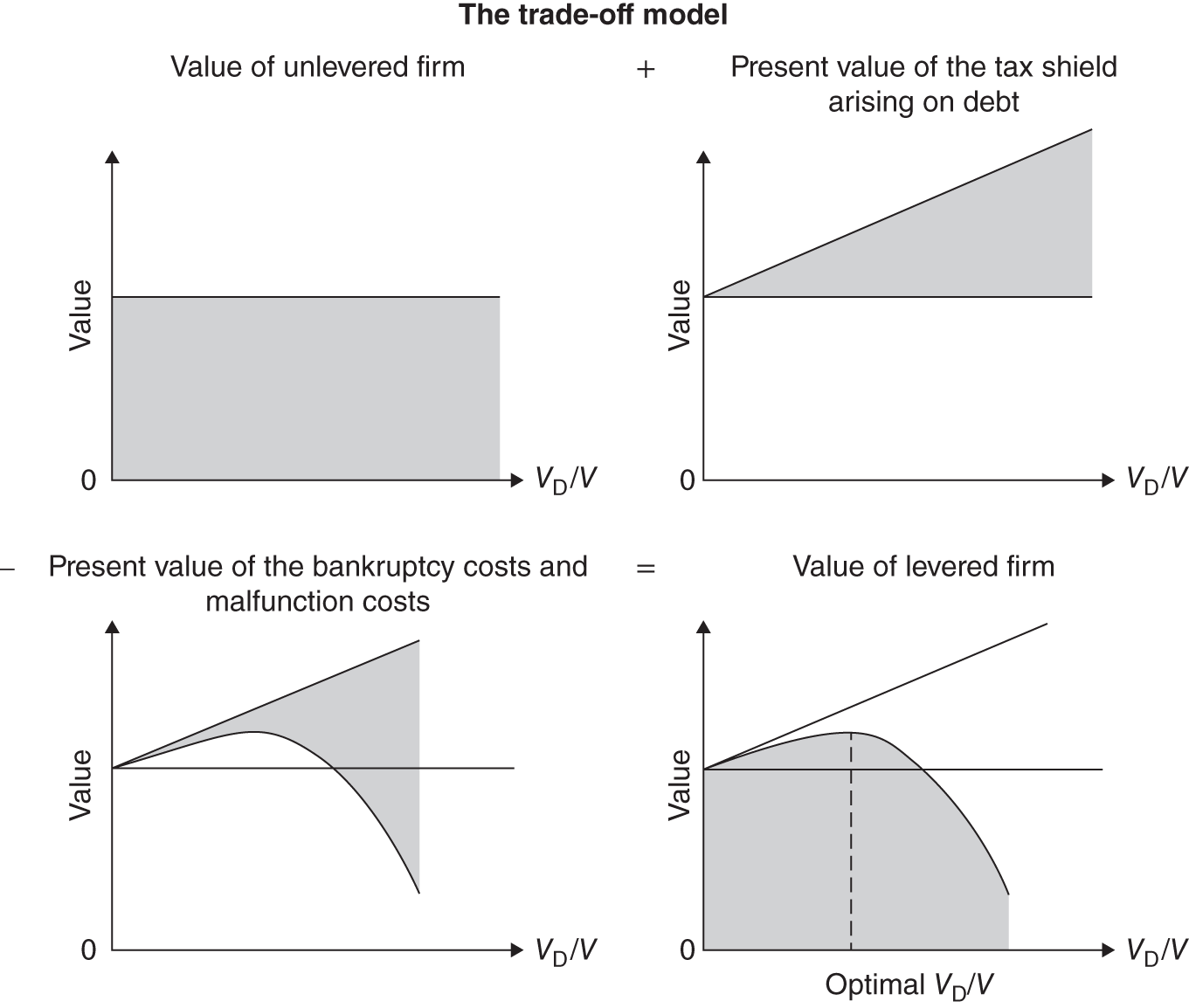

Using the cost of debt is justified if we are certain that the tax savings are permanent. In addition, this allows us to use a particularly simple formula:

Nevertheless, there are good reasons to prefer to discount the savings at the cost of equity, since it would be difficult to assume that the company will continually carry the same debt, generate profits and be taxed at the same rate. As the tax savings accrue to the shareholders, so should it be reasonable to discount them at the rate of return required by those shareholders.

Bear in mind that these tax savings only apply if the company has sufficient earnings power and does not benefit from any other tax exemptions, such as tax-loss carryforwards.

2/ COSTS OF FINANCIAL DISTRESS

We have seen that the more debt a firm carries, the greater the risk that it will not be able to meet its commitments. If the worst comes to the worst, the company files for bankruptcy, which in the final analysis simply means that assets are reallocated to more profitable ventures.

For investors with a well-diversified portfolio, the cost of the bankruptcy will theoretically be nil, since when a company is discontinued, its assets (market share, customers, factories, etc.) are taken over by others who will manage them better. One person’s loss is another person’s gain! If the investor has a diversified portfolio, the capital losses will be offset by other capital gains.

In practice, however, markets are not perfect and we all know that even if bankruptcies are a means of reallocating resources, they carry a very real cost to those involved. These include:

- Direct costs: redundancy payments, legal fees, administrative costs, shareholders’ efforts to receive a liquidation dividend.

- Indirect costs: order cancellations (for fear they will not be honoured), less trade credit (because it may not be repaid), reduced productivity (strikes, underutilisation of production capacity), no more access to financing (even for profitable projects); as well as incalculable human costs.

One could say that bankruptcy occurs when shareholders refuse to inject more funds once they have concluded that their initial investment is lost. In essence, they are handing the company over to its creditors, who then become the new shareholders. The creditors bear all the costs of the malfunctioning company, thus further reducing their chances of getting repaid.

Even without going to the extremes of bankruptcy, a highly levered company in financial distress faces certain dysfunctions that reduce its value. It may have to cut back on R&D expenditure, maintenance, training or marketing expenses in order to meet its debt payments and will find it increasingly difficult to raise new funding, even for profitable investment projects.

After factoring all these costs into the equation, we can say that:

or, as illustrated by the following figure:

Because of the tax deduction, debt can, in fact, create value. A levered company may be worth more than if it had only equity financing. However, there are two good reasons why this advantage should not be overstated. Firstly, when a company with excessive debt is in financial distress, its tax advantage disappears, since it no longer generates sufficient profits. Secondly, the high debt level may lead to restructuring costs and lost investment opportunities if financing is no longer available. As a result, debt should not exceed a certain level.

In 2000, Graham found that the value of the tax advantage of interest expenses is around 9.7%, and it goes down to 4.3% if personal taxation of investors is also considered. Almeida and Philippon (2007) have, on the other hand, estimated the bankruptcy costs; they believe the right percentage is around 4.5% – in brief, it seems that one effect “perfectly” compensates the other. More recent works quoted in the bibliography found similar results.

In fact, Modigliani and Miller’s theory states the obvious: all economic players want to reduce their tax charge! A word of caution, however. Corporate managers who focus too narrowly on reducing tax charges may end up making the wrong decisions.

3/ INTRODUCING PERSONAL TAXES, A MAJOR IMPROVEMENT TO THE PREVIOUS REASONING

In 1977, Miller released a new study in which he revisited the observation made with Modigliani in 1958 that there is no one optimal capital structure. This time, however, he factored in both corporate and personal taxes.

Miller claimed that the taxes paid by investors can cancel out those paid by companies. This would mean that the value of the firm would remain the same regardless of the type of financing used. Again, there should be no optimal capital structure.

Miller based his argument on the assumption that equity income is not taxed, and that the tax rate on interest income is marginally equal to the corporate tax rate. In other words, the tax advantage of debt at the level of the company is neutralised by the tax advantage of equity at the level of the investor.

Who benefits from taxation? No research has shown that the tax advantage of debt is not shared equally between creditor and debtor. In recent years, tax reforms have led to the disappearance of tax friction and thus the debt advantage is tending to disappear. For certain types of investors, there is therefore no longer any tax friction when collecting their income, which is fundamental.

Say a company has an enterprise value of 1,000. Regardless of its type of financing, investors require a 7.5% return after corporate and personal income taxes. Bear in mind that this rate is not comparable with that determined by the CAPM (r F + β × (r M − r F)), which is calculated before personal taxation.

Let’s take a country where (realistically) the main tax rates are:

- corporate tax: 28.4%;

- tax on dividends: 17.2%;

- tax on interest income: 30%.

Now let us assume that the company has an operating profit of 135. This corresponds to a cost of equity of 8% if it is entirely equity-financed.

| Enterprise value | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equity | 1,000 | 750 | 500 | 250 |

| Debt | 0 | 250 | 500 | 750 |

| Interest rate | 2.0% | 3.0% | 5.0% | |

| Operating profit | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| − Interest expense | 0 | 5 | 15 | 37.5 |

| = Pre-tax profit | 135 | 130 | 120 | 98 |

| − Corporate income tax at 28.4% | 38 | 37 | 34 | 28 |

| = Net profit | 97 | 93 | 86 | 70 |

| Dividend | 97 | 93 | 86 | 70 |

| Personal income tax: | ||||

| On dividends (17.2%) | 17 | 16 | 15 | 12 |

| On interest (30%) | 0 | 2 | 5 | 11 |

| Shareholders’ net income | 80 | 77 | 71 | 58 |

| Shareholders’ net return | 8% | 10.3% | 14.2% | 23.1% |

| Creditors’ net income | 0 | 4 | 11 | 26 |

| Creditors’ net return | 1.4% | 2.1% | 3.5% | |

| Net income for investors | 80 | 81 | 82 | 84 |

| Total taxes | 55 | 54 | 53 | 51 |

The net return of the investor, who is both shareholder and creditor of the firm, can be calculated depending on whether net debt represents 0%, 33.3%, 100% or three times the amount of equity.

The value created by debt must thus be measured in terms of the increase in net income for investors (shareholders and creditors). Our example shows that flows do not increase significantly even when the debt level is particularly high.

Using the table below, we can even see that in certain countries, such as the UK, the tax savings on corporate debt are more than offset by the personal taxes levied.

TAX RATES IN VARIOUS COUNTRIES (%)

| Country | On dividends | On capital gains | On interests | On corporate earnings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 17.2% | 17.2% | 30% | 28.41% |

| Germany | 26.4% | 26.4% | 26.4% | 30%–33% |

| Italy | 26% | 26% | 12.5% or 26% | 27.9% |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 10% or 15% | 0% | 13.5% or 18% | 25% |

| Lebanon | 10% | 15% | 10% | 17% |

| Morocco | 10% | 15% (listed) – 20% | 30% | 10%, 20% and 31% |

| Spain | 19% to 26% | 19% to 26% | 19% to 26% | 25% |

| Switzerland | 19% to 41% | 0% | 19 to 41% | 11.5%–24.2% |

| Tunisia | 10% | 10% | 0 to 35% (income tax) | 10%, 15% or 35% |

| UK | 0%, 7.5%–32.5% or 38.1% | 10% or 20% | 0%, 20%, 40% or 45% | 21% |

| US | Income tax or 0% to 20% | 0 to 20% | 37% (income tax) | 27% |

Bear in mind, too, that companies do not always use the tax advantages of debt since there are other options, such as accelerated depreciation, provisions, etc.

4/ LIMITS TO THE DEDUCTIBILITY OF INTEREST AND NOTIONAL INTEREST, THE THIRD LIMIT

In a certain number of jurisdictions, governments have introduced mechanisms to rebalance taxation of revenues from capital gains and debt.

These measures can take the form of a limitation of the deductibility of interest. For example in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK and USA, interest is deductible only up to 30% of EBITDA.

In some countries, to make equity financing more attractive, firms can deduct notional interest computed on equity from taxable income. This is the case in Belgium, Brazil and Italy.

Section 33.2 DEBT TO CONTROL MANAGEMENT

Now let’s use the agency theory concepts on our first financial question: the analysis of the capital structure.

1/ DEBT AS A MEANS OF CONTROLLING CORPORATE MANAGERS

Now let us examine the interests of non-shareholder executives. They may be tempted to shun debt in order to avoid the corresponding constraints, such as a higher breakeven threshold, interest payments and principal repayments. Corporate managers are highly risk averse and their natural inclination is to accumulate cash rather than resort to debt to finance investments. Debt financing avoids this trap, since the debt repayment prevents surplus cash from accumulating.

Shareholders encourage debt as well, because it stimulates performance. The more debt a company has, the higher its risk. In the event of financial difficulties, corporate executives may lose their jobs and the attendant compensation package and remuneration in kind. This threat is considered to be sufficiently dissuasive to encourage sound management, generating optimal liquidity to service the debt and engage in profitable investments.

Shareholders are keen to leverage the firm as debt is an efficient tool to put managers under pressure and hence solve agency issues.

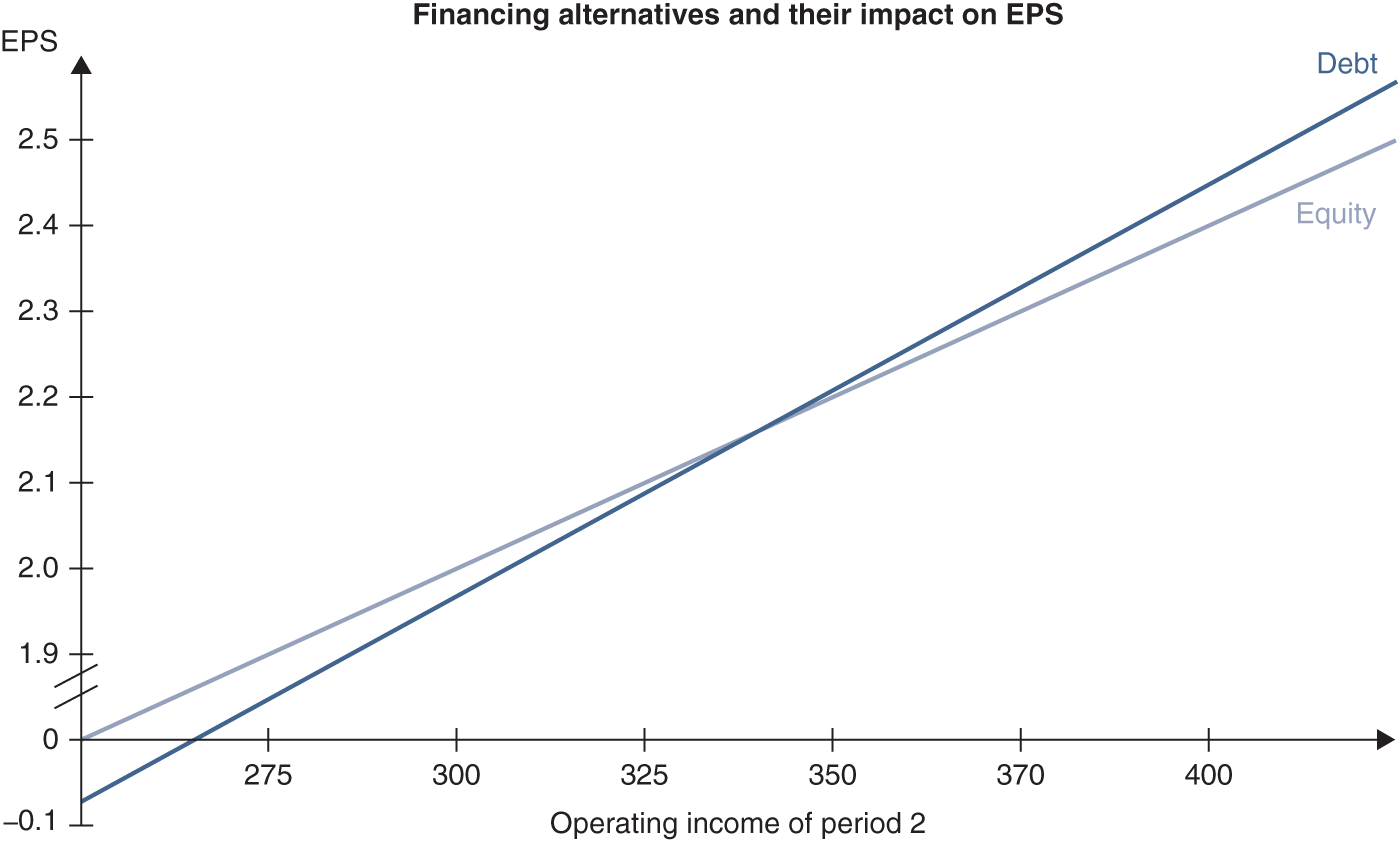

Given that the parameters of debt are reflected in a company’s cash situation while equity financing translates into capital gains or losses at shareholder level, management will be particularly intent on the success of its debt-financed investment projects. This is another, indirect, limitation of the perfect markets theory: since the various forms of financing do not offer the same incentives to corporate executives, financing does indeed influence the choice of investment.

This would indicate that a levered company is more flexible and responsive than an unlevered company. This hypothesis was tested and proven by Ofek, who showed that the more debt they carry, the faster listed US companies react to a crisis, by filing for bankruptcy, curtailing dividend payouts or reducing the payroll.

Debt is thus an internal means of controlling management preferred by shareholders. In Chapter 45 we shall see that another is the threat of a takeover bid.

However, the use of debt has its limits. When a group’s corporate structure becomes totally unbalanced, debt no longer acts as an incentive for management. On the contrary, the corporate manager will be tempted to continue expanding via debt until the group has become too big to fail, like RBS, Fortis, AIG, Citi, etc., until the concept of “too big to fail” is tested (Lehman Brothers). This risk is called “moral hazard”.

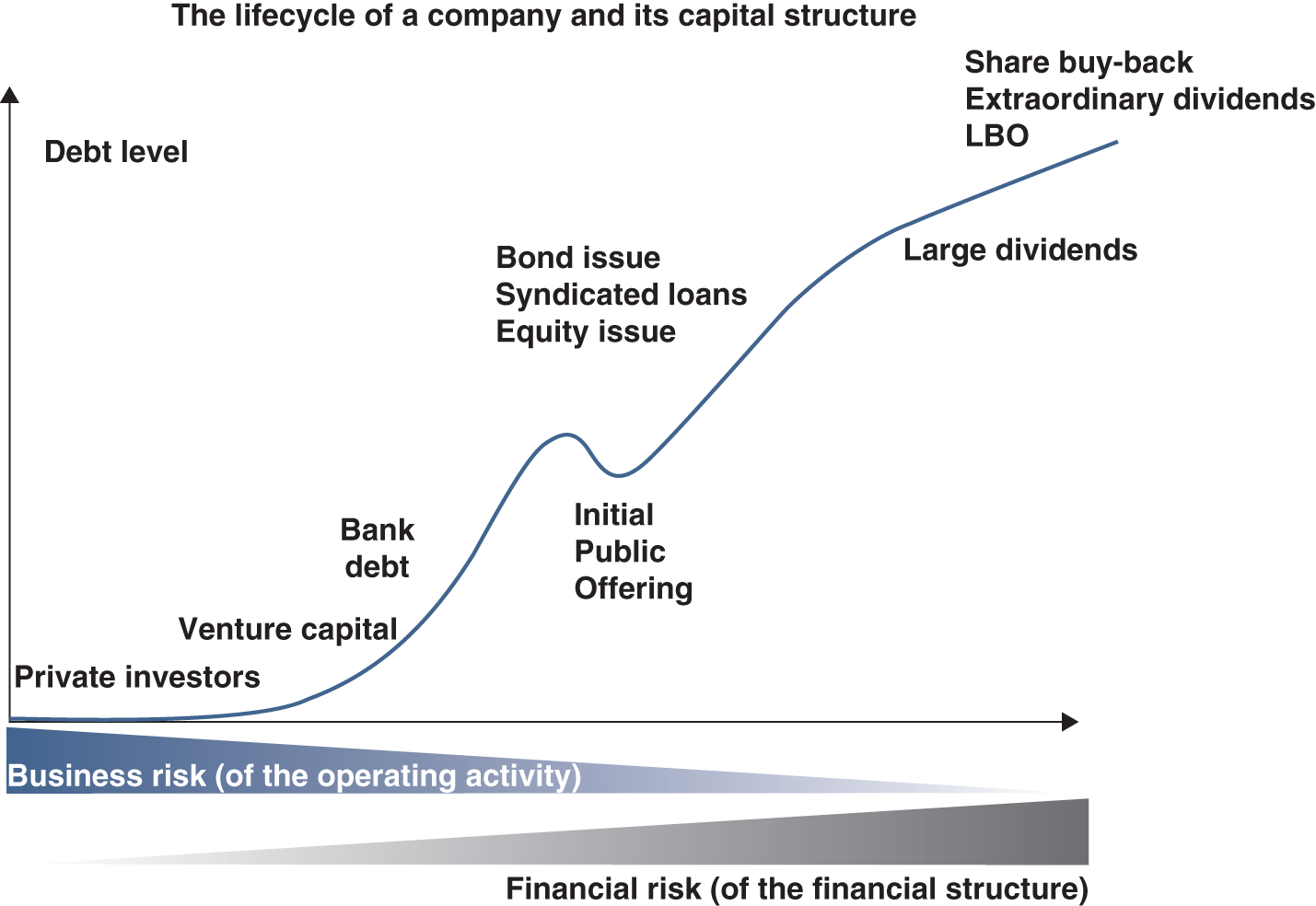

2/ LBOS: THIS LOGIC PUSHED TO THE EXTREME

An LBO (or Leveraged Buy-Out, see Chapter 47) is the acquisition, generally by management (MBO), of all of a company’s shares using largely borrowed funds. It becomes a leveraged buildup if it then uses debt to buy other companies in order to increase its standing in the sector. It is generally thought that the purpose of the funds devoted to LBOs is to use accounting leverage to obtain better returns. In fact, the success of LBOs cannot be attributed to accounting leverage, since we have already seen that this alone does not create value.

The real reason for the success of LBOs is that, when it has a stake in the company, management is far more committed to making the company a success. With management most often holding a share of the equity, resource allocation will be designed to benefit shareholders. Executives have a two-fold incentive: to enhance their existing or future stake in the capital and to safeguard their jobs and reputation by ensuring that the company does not go broke. It thus becomes a classic case of the carrot and the stick!

Mature, highly profitable companies with few investments to make are the most likely candidates for an LBO. Jensen (1986) demonstrated that, in the absence of heavy debt, the executives of such companies will be strongly tempted to use the substantial free cash flow to grow to the detriment of profits by overinvesting or diversifying into other businesses, two strategies that destroy value.

Section 33.3 SIGNALLING AND DEBT POLICY

Signalling theory is based on the strong assumption that corporate managers are better informed about their companies than the suppliers of funding. This means that they are in a better position to foresee the company’s future flows and know what state their company is in. Consequently, any signal they send indicating that flows will be better than expected, or that risks will be lower, may enable the investor to create value. Investors are therefore constantly on the watch for such signals. But for the signals to be credible, there must be a penalty for the wrong signals in order to dissuade companies from deliberately misleading the market.

In the context of information asymmetry, markets would not understand why a corporate manager would borrow to undertake a very risky and unprofitable venture. After all, if the venture fails, they risk losing their job or worse, if the venture causes the company to fail. So debt is a strong signal for profitability, but even more for risk. It is unlikely that a CEO would resort to debt financing if they knew that in a worst-case scenario they would not be able to repay the debt.

Ross (1977) has demonstrated that any change in financing policy changes investors’ perception of the company and is therefore a market signal.

It is thus obvious that an increase in debt increases the risk on equity. The managers of a company that has raised its gearing rate are, in effect, signalling to the markets that they are aware of the state of nature, that it is favourable and that they are confident that the company’s performance will allow them to pay the additional financial expenses and pay back the new debt.

This signal carries its own penalty if it is wrong. If the signal is false, i.e. if the company’s actual prospects are not good at all, the extra debt will create financial difficulties that will ultimately lead, in one form or another, to the dismissal of its executives. In this scheme, managers have a strong incentive to send the correct signal by ensuring that the firm’s debt corresponds to their understanding of its repayment capacity.

Ross has shown that, assuming managers have privileged information about their own company, they will send the correct signal on the condition that the marginal gain derived from an incorrect signal is lower than the sanction suffered if the company is liquidated. “They put their money where their mouths are.” This explains why debt policies vary from one company to another: they simply reflect the variable prospects of the individual companies.

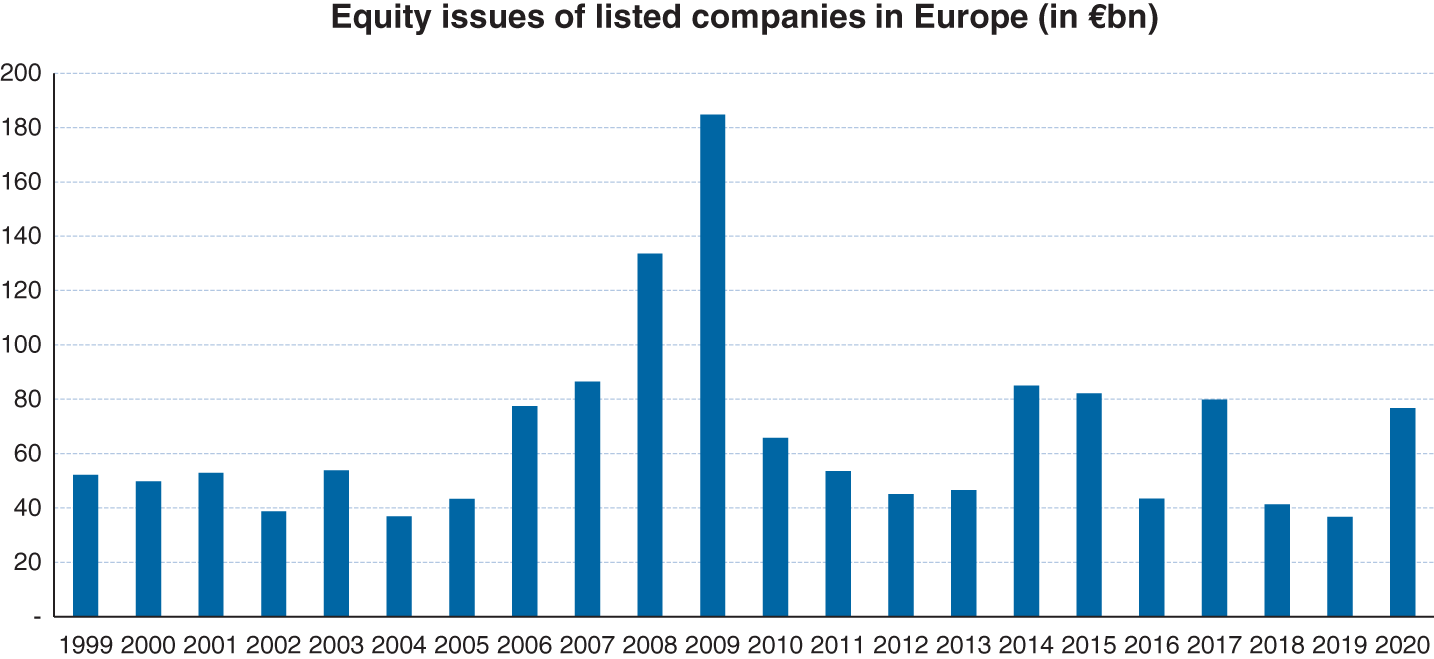

When a company announces a capital increase, research has shown that its share price generally drops by an average of 3%. The market reasons that corporate managers would not increase capital if, based on the inside information available to them, they thought it was undervalued, since this would dilute the existing shareholdings in unfavourable conditions. If there is no pressing reason for the capital increase, investors will infer that, based on their inside information, the managers consider the share price to be too high and that this is why the existing shareholders have accepted the capital increase. On the other hand, research has shown too that the announcement of a bond issue has no material impact on share prices.

This explains why financial investors prefer to subscribe to capital increases rather than buy from existing shareholders. It is also the reason why in most countries, top managers and all directors must disclose the number of shares they hold or control in the companies they work for or of which they are board members.

Section 33.4 INFORMATION ASYMMETRIES AND THE PECKING ORDER THEORY

Having established that information asymmetry carries a cost, our next task is to determine what type of financing carries the lowest cost in this respect.

The uncontested champion is, of course, internal financing, which requires no special procedures. Its advantage is simplicity.

Debt comes next, but only low-risk debt with plenty of guarantees (pledges) and covenants restricting the risk to creditors and thus making it more palatable to them. This is followed by riskier forms of debt and hybrid securities.

Capital increases come last, because they are automatically interpreted as a negative signal. To counter this, the information asymmetry must be reduced by means of roadshows, one-to-one meetings, prospectuses and advertising campaigns. Investors have to be persuaded that the issue offers good value for money!

In an article published in 1984, Myers elaborates on a theory initially put forward by Donaldson in 1961, stating that, according to this pecking order theory, companies prioritise their sources of financing.

As can be seen, although corporate managers do not choose the type of financing arbitrarily, they do so without great enthusiasm, since they all carry the same cost relative to their risk. The pecking order is determined by the law of least effort. Managers do not have to “raise” internal financing, and they will always endeavour to limit intermediation costs, which are the highest on share issues.

This theory explains fairly well the situation of highly profitable listed companies with little debt because they are almost exclusively self-financing, or that of SMEs which only increase their capital when their debt capacity is saturated.

In Chapter 34 we will see how potential or actual conflicts of interest between shareholders and lenders due to the financial structure of the company can be analysed and resolved through options.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

Chapter 34. DEBT, EQUITY AND OPTIONS THEORY

Light too bright to see by

The theories of corporate finance examined so far may have given the impression that the only difference between debt and equity is the required rate of return. However, there is a big difference between the 10% return required by creditors and that required by shareholders.

Shareholders simply hope to achieve this rate, which forms an average of rates that can be either positive or negative. The actual return can range from 0% to infinity, with the entire range of variations in between!

Creditors are assured of receiving the required rate, but never more. They can only hope to earn the 10% return but, with a few exceptions, this hope is almost always fulfilled.

So here we have the first distinction between creditors and shareholders: the probability distribution of their remuneration is completely different.

That said, although the creditor’s risk is very low, it is not nil. Capitalism is built on the concept of corporation, which legally restricts shareholders’ liability with respect to creditors. When a company defaults, shareholders hold a “trump card” that allows them to hand the company, including its liabilities, over to the lenders.

In the rest of this chapter, we will concentrate on the valuation of companies in which shareholders’ responsibility is limited to the amount they have invested. This applies to the vast majority of all companies in modern capitalism, be they corporations, limited liability companies or sole proprietorship with limited liability.

This is the fundamental difference between shareholders and creditors: the former can lose their entire investment, but also hope for unlimited gains, while the latter will at best earn the flows programmed at the beginning of the contract.

Keep this in mind as we use options to analyse corporate structure and, more importantly, the relationship between shareholders and creditors.

Section 34.1 ANALYSING THE FIRM IN LIGHT OF OPTIONS THEORY

To keep our presentation simple, we shall take the example of a joint stock company in which enterprise value EV is divided between debt (VD) and equity (VE).

We shall also assume that the company has issued only one type of debt – zero-coupon bonds – redeemable upon maturity at full face value (principal and interest) for 100.

Depending on the enterprise value when the debt matures, two outcomes are possible:

- The enterprise value is higher than the amount of debt to be redeemed (e.g. EV = 120). In this case, the shareholders let the company repay the lenders and take the residual value of 20.

- The enterprise value is lower than the amount of debt to be redeemed (e.g. EV = 70). The shareholders may then invoke their limited liability clause, forfeiting only their investment, and transfer the company to the lenders who will bear the difference between the enterprise value and their claim.

Now let us analyse this situation in terms of options. From an economic standpoint, shareholders have a call option (known as a European call if it can only be exercised at the end of its life) on the firm’s assets. Its features are:

- Underlying asset = operating assets.

- Exercise price = amount of debt to be reimbursed (100).

- Volatility = volatility of the underlying assets, i.e. operating assets.

- Maturity = expiration date.

- Interest rate = risk-free rate corresponding to the maturity of the option.

At the expiration date, shareholders either exercise their call option by repaying the lenders, or they abandon it. The value of the option is none other than the value of equity (VE).

The lender, on the other hand, who has invested in the firm at no risk, has sold the shareholders a put option on operating assets. We have just seen that in the event of default, the creditors may find themselves the unwilling owners of the company. Rather than recouping the amount they lent, they get only the value of the company back. In other words, they have “bought” the company in exchange for the outstanding amount of debt.

The sale of this (European-style) put option results in additional remuneration for the debtholder, which, together with the risk-free rate, constitutes the total return. This is only fair, since the debtholder runs the risk that the shareholders will exercise their put option; in other words, that the company will not pay back the debt.

The features of the put option are:

- Underlying asset = operating assets.

- Exercise price = amount of debt redeemable upon maturity (100).

- Volatility = volatility of the underlying asset, i.e. the operating assets.

- Maturity = maturity of the debt.

- Interest rate = risk-free rate corresponding to the maturity of the option.

The value of this option is equal to the difference between the value of the loan computed by discounting its cash flows at the risk-free rate and its market value (discounted at a rate that takes into account the default risk, i.e. the cost of debt kD). This is the risk premium that arises between any loan and its risk-free equivalent.

All this means is that the debtholder has lent the company 103 at an interest rate equal to the risk-free rate. The company should have received 103, but the value of the loan is only 100 after discounting the flows at the normal rate of return required in view of the company’s risk, rather than the risk-free rate.

The company uses the balance of 3, which represents the price of the credit risk, to buy a put option on its operating assets. In short, the company receives a net of 100 while the bank pays a net of 100 for a risky claim since it has sold a put option on its operating assets that the company, and therefore the shareholders, will exercise if its value is lower than that of the outstanding debt at maturity. By exercising the option, the company, and thus its shareholders, discharges its debt by transferring ownership of the operating assets to the creditors.

In conclusion, we see that, depending on the situation at the redemption date, one of the following two will apply:

- if VD < V, the value of the call option is higher than 0, the value of the put option is zero and equity is positive;

- if VD > V, the value of the call option is zero, the value of the put option is higher than 0 and the equity is worthless.

Section 34.2 CONTRIBUTION OF OPTIONS THEORY TO THE VALUATION OF EQUITY

We have demonstrated that the value of a firm’s equity is comparable to the value of a call option on its operating assets. The option’s exercise price is the amount of debt to be repaid at maturity, the life of the option is that of the debt, and its underlying asset is the firm’s operating assets.

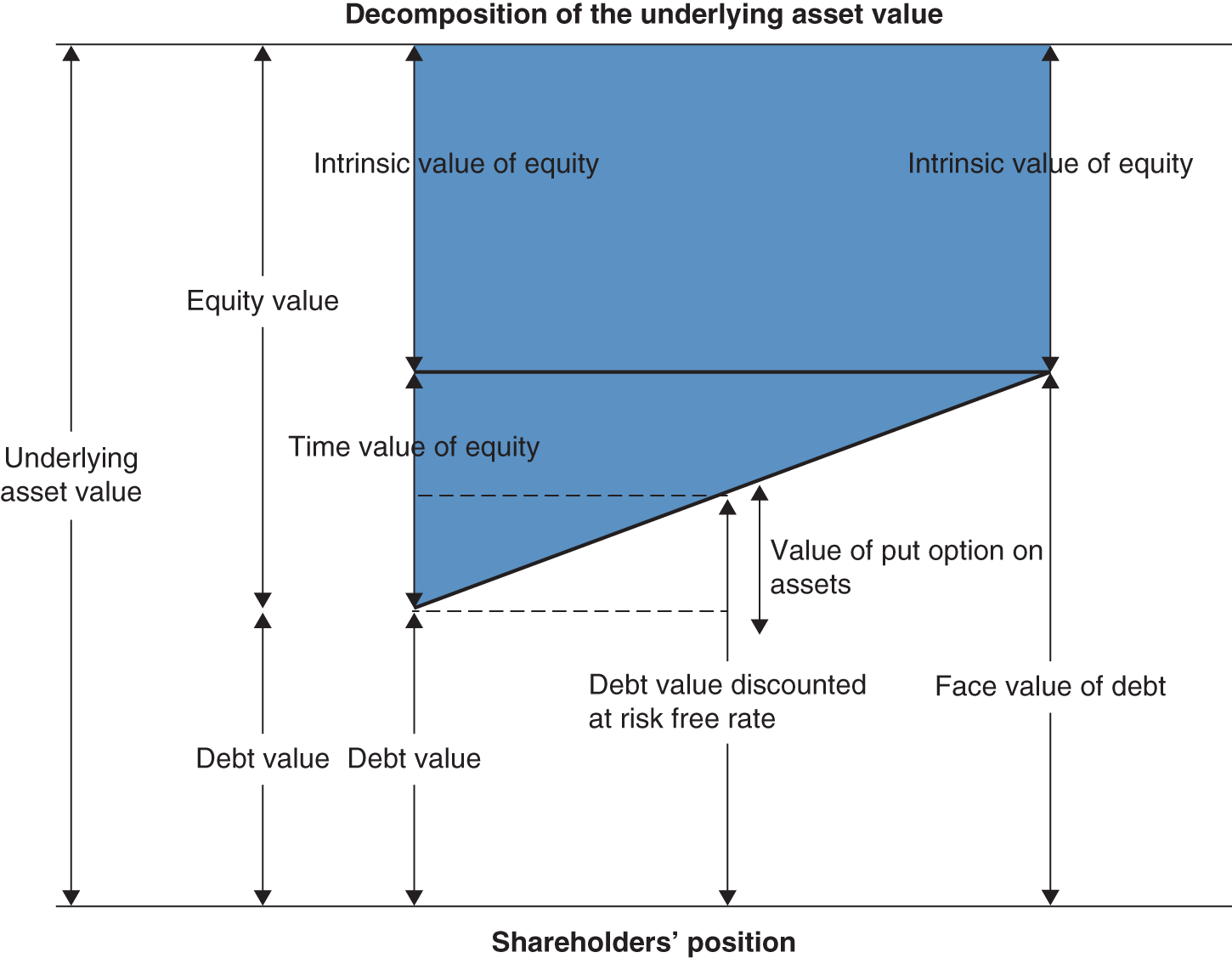

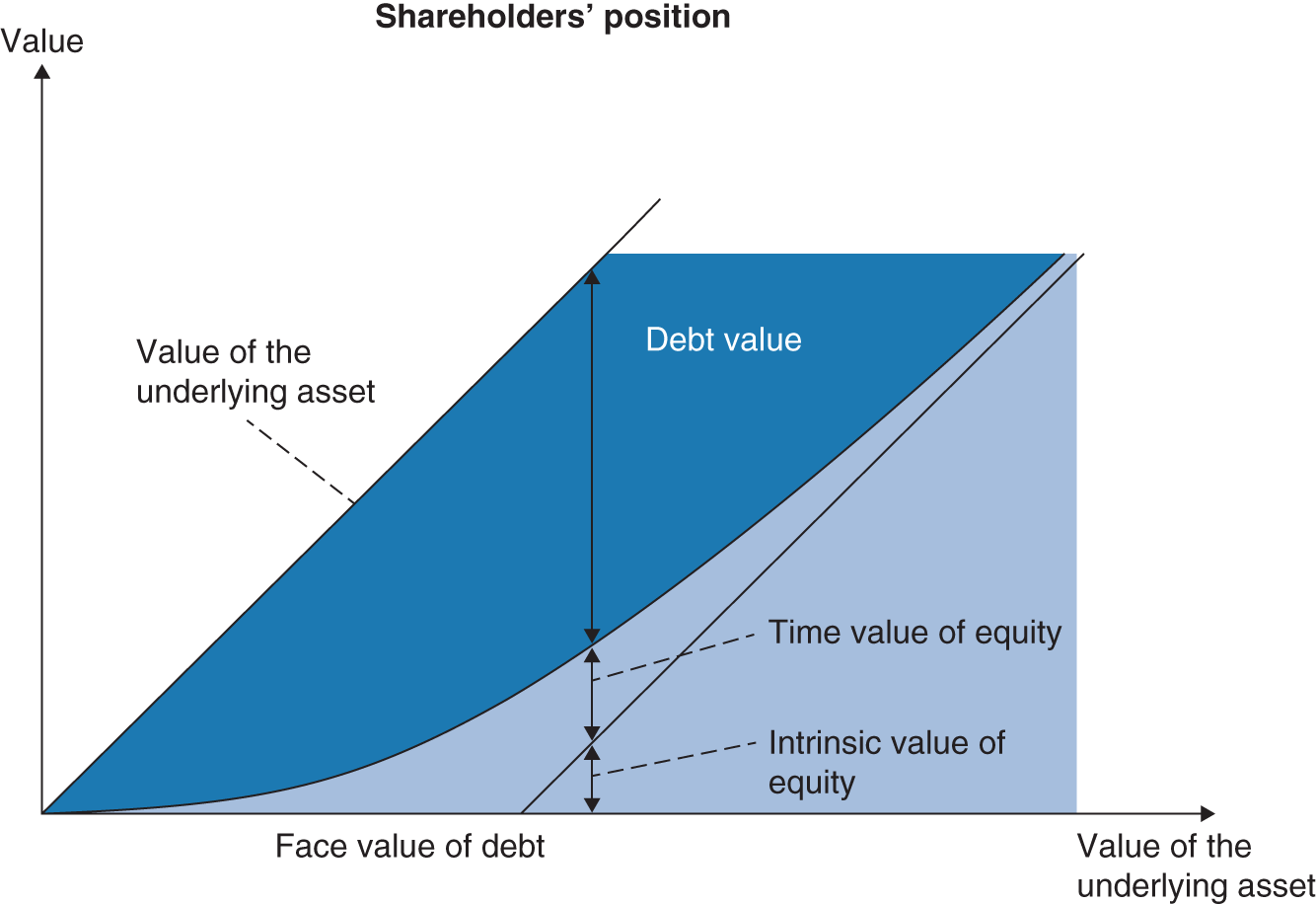

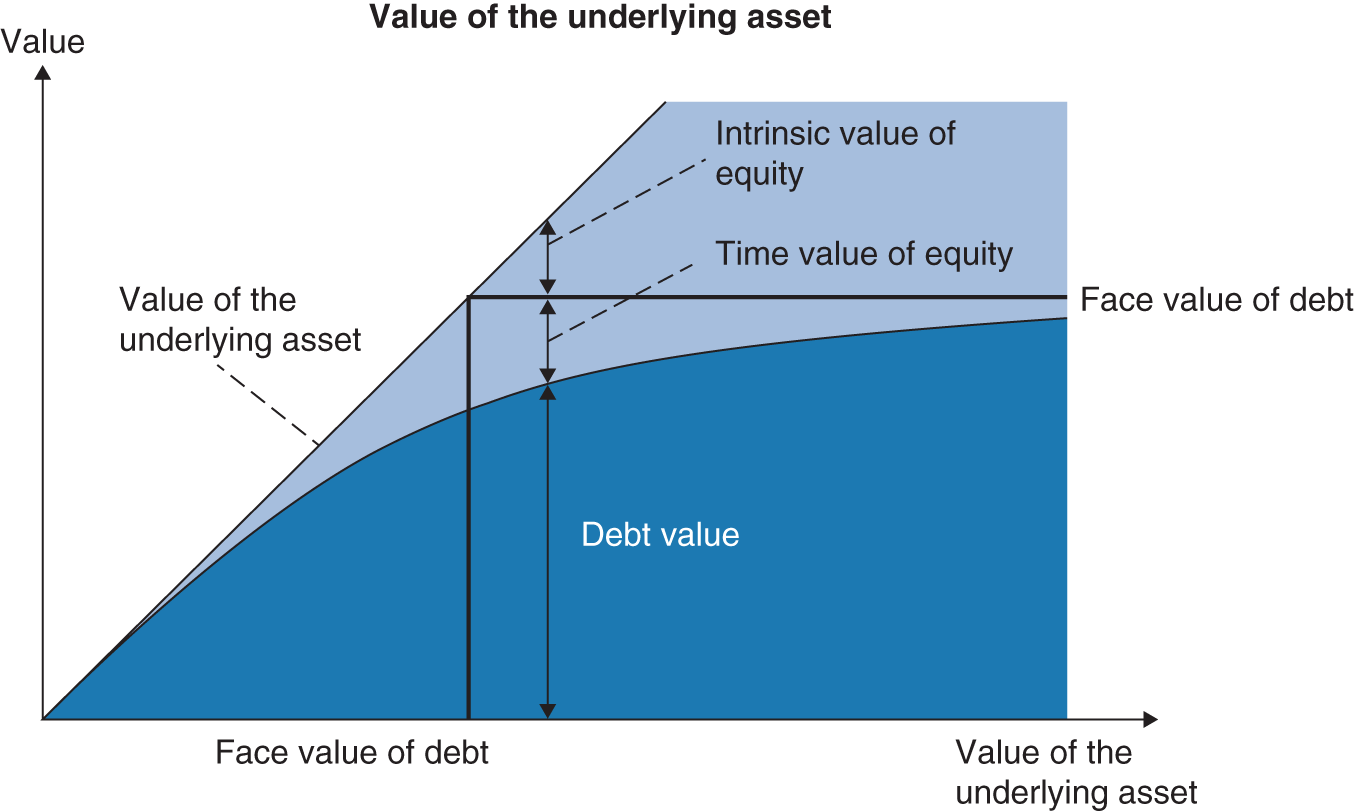

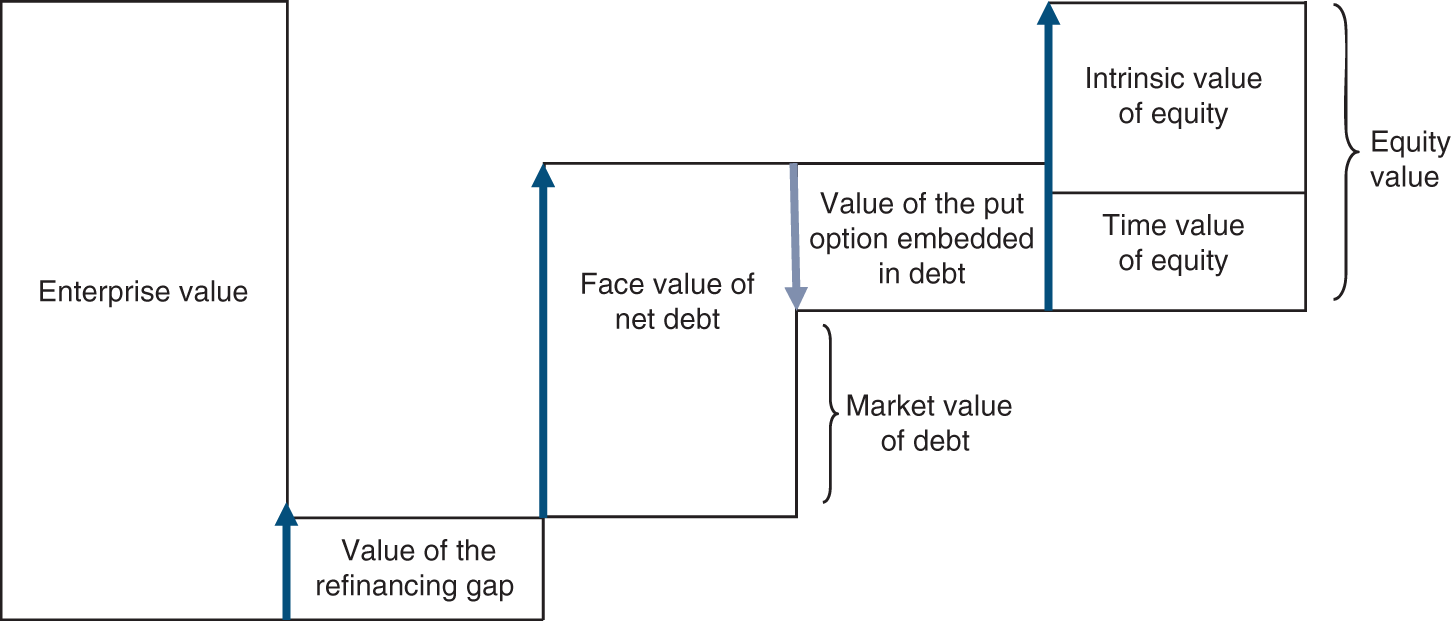

This means that, at the valuation date, the value of equity is made up of an intrinsic value and a time value. The intrinsic value of the call option is the difference between the present value of operating assets and the debt to be repaid upon maturity. The time value corresponds to the difference between the total value of equity and the intrinsic value.

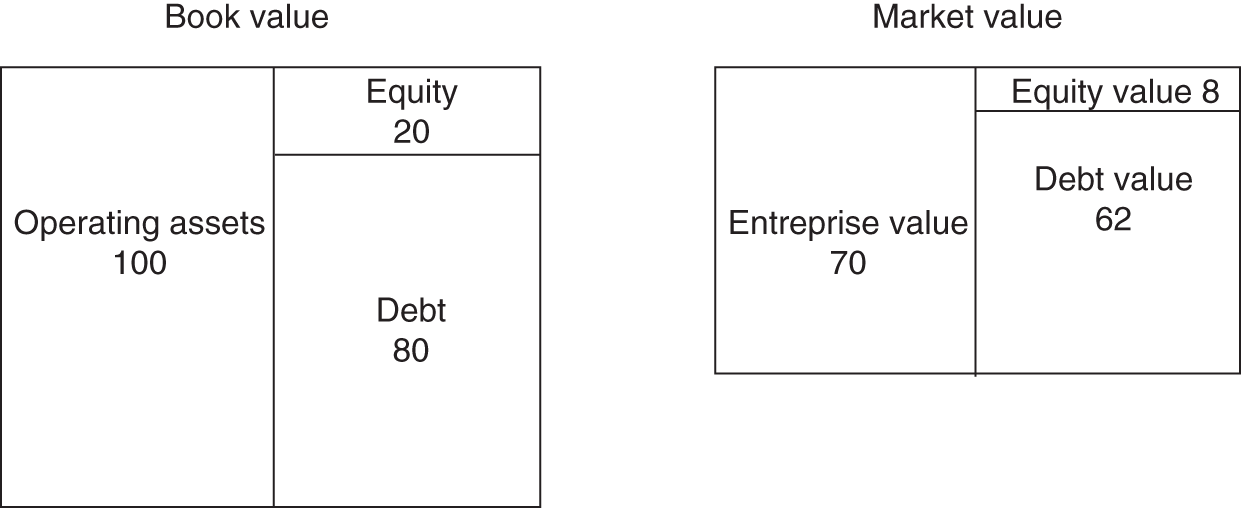

Take, for example, a company where the return on capital employed is lower than that required by investors in view of the related risk. The market value is thus lower than the book value:

If the debt were to mature today, the shareholders would exercise their put option since operating assets are worth only 70 while the outstanding debt is 80. The company would have to file for bankruptcy. Fortunately, the debt is not redeemable today but only in, say, two years’ time. By then, the enterprise value, i.e. the value of operating assets, may have risen to over 80. In that case, equity will have an intrinsic value equal to the difference between the enterprise value at the redemption date and the amount to be redeemed (in our case, 80).

Today, however, the intrinsic value of equity is zero (it cannot be negative as seen in Section 23.3) and the present value of equity (8) can only be explained by its time value. It represents the hope that, when the debt matures two years hence, enterprise value will have risen enough to exceed the amount of debt to be repaid, giving the equity an intrinsic value.

As seen in the following graphs, a company’s financial position can be considered from either the shareholders’ or the creditors’ standpoint.

By now you must (might) be eager to apply your new-found knowledge of options to corporate finance!

- The time value of an option increases with the volatility of the underlying asset.

The more economic or industrial risk on a company, the higher the volatility of its operating assets and the higher the time value of its equity.

The options method is thus theoretically relevant to value large, risky projects financed by debt, such as oil drilling in northern Siberia, leisure parks, etc., or those with inherent volatility, such as biotech start-ups.

- The time value of an option depends on the position of the strike price relative to the market value of the underlying asset.

When the call option is out-of-the-money (enterprise value lower than outstanding debt), the company’s equity has only time value. Shareholders hope for an improvement in the company, whose equity has no intrinsic value.

When the call option is at-the-money (enterprise value equal to debt at maturity), the time value of equity is at its highest and anything can happen. Using the options method to value equity is now particularly relevant, since it can quantify shareholders’ anticipation.

When call option is in-the-money (enterprise value higher than outstanding debt at maturity), the intrinsic value of equity quickly outweighs the time value. The risk on the debt held by the lenders decreases and becomes nearly non-existent when the enterprise value tends towards infinity. This brings us back to the traditional idea that the higher the enterprise value, the less risk creditors have of a default, and the more the cost of debt approaches the risk-free rate.

The options method is therefore applied to companies that carry heavy debt or are very risky.

- The time value of an option increases with its maturity.

This is why it is so important for companies in distress to reschedule debt payments, preferably at very long maturities.

The example below illustrates the use of options to value equity.

Take a company that has both debt and equity financing and let us assume its debt is 100, redeemable in one year. If, based on its degree of risk, the debt carries 6% interest, then the amount to be paid to creditors one year later is 106.

If the firm’s value is 150 at the time of calculation, then the value of equity – defined as the difference between enterprise value and the value of debt – will be 150 − 100 = 50.

What happens if we apply options theory to this value?

We shall assume the risk-free rate is 5%. The discounted value of the debt + interest payment at the risk-free rate is 106 / 1.05, or 100.95.

The value of debt can be expressed as:

Value of debt = Value of debt at the risk-free rate – Value of a put

i.e. the value of the put = 100.95 − 100 = 0.95.

We know that the value of equity breaks down into its intrinsic and time value:

You can see that, for this company with limited risk, the time value measuring the actual risk is far lower than the intrinsic value. Similarly, the value of the put, which acts as a risk premium, is very low as well.

Now, let’s increase the risk of operating assets and assume that the interest rate required by the creditors is 15% rather than 6%, corresponding to a 10% risk premium as the risk-free rate is 5%. The amount to be repaid in one year is thus 115.

The value of the debt discounted at the risk-free rate is 115 / 1.05, or 109.52. The value of the put is thus 109.52 − 100 = 9.52.

Note that the risk premium for this company is much higher than in the preceding example, reflecting the increasing probability that the company will default on its debt. This debt is now very similar to a high-yield or non-investment grade debt (see Section 20.6).

The value of equity, which is still 50, breaks down into an intrinsic value of 35 (150 − 115) and a time value of 15 (50 − 35). Since there is more risk than in our previous example, the time value accounts for a higher share of the equity value.

Section 34.3 USING OPTIONS THEORY TO ANALYSE A COMPANY’S FINANCIAL DECISIONS

Options theory helps us understand how major corporate financial decisions (choice of capital structure, dividend payout, investment decisions, etc.) affect shareholders and creditors differently, and how they can result in a transfer of value between the two.

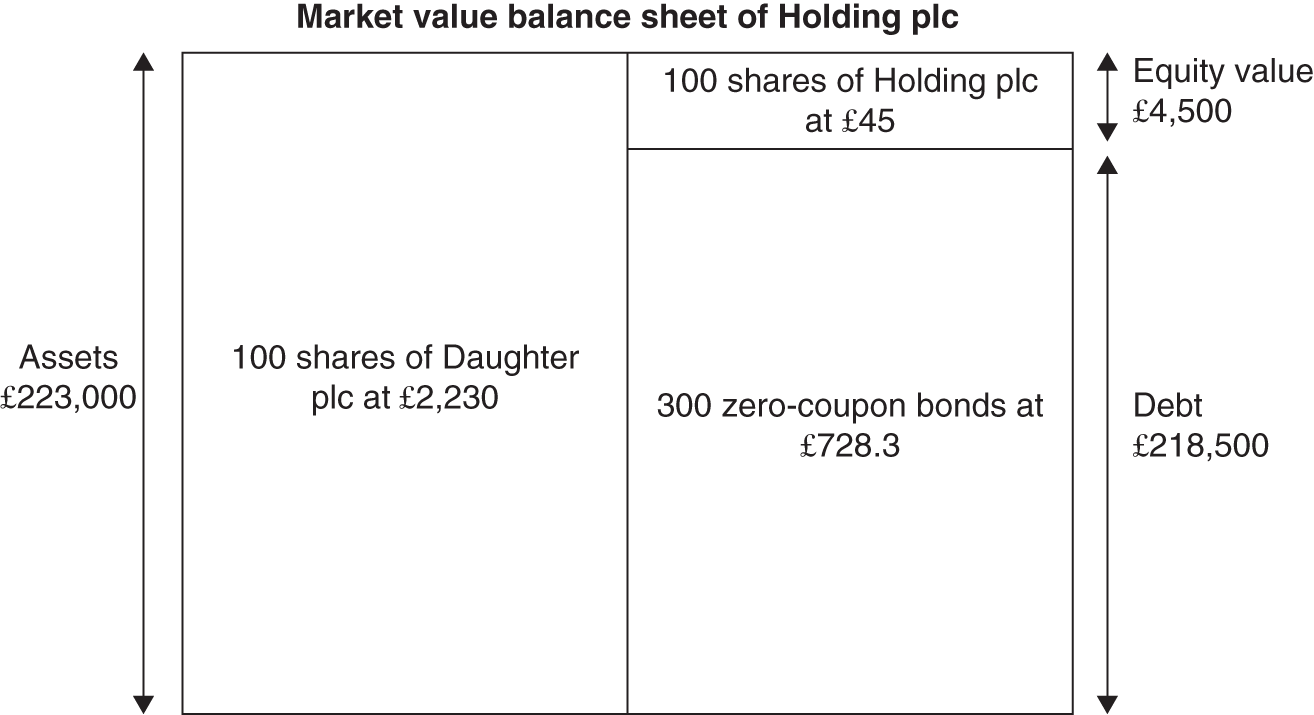

The table below lists the closing prices for a call option on a Daughter plc share at various exercise prices:

| Exercise price (£) | Value of a 3-year call option on Daughter plc (£) |

|---|---|

| 2,600 | 130 |

| 2,800 | 80 |

| 3,000 | 45 |

| 3,200 | 31 |

The enterprise value of Holding plc is equal to the number of Daughter plc shares multiplied by their market price, i.e. £223,000.

Consider each of the 100 shares issued by Holding plc as being an option on its operating assets (the shares of Daughter plc), i.e. £223,000, with an exercise price that is equal to the amount of Holding plc debt outstanding, giving 300 bonds × £1,000 = £300,000.

Each Holding plc share can thus be considered to be a call option with an exercise price of £300,000 / 100 shares = £3,000, and a maturity of three years.

According to the table above, Holding plc’s equity value is thus £45 × 100 shares = £4,500.

One bond is therefore worth £728.3 (£218,500 / 300), corresponding to an implied yield of 11.1% (in fact: 728.3 = 1,000 / (1 + 0.111)3).

We will now discuss a few major financing or investment decisions in a context of equilibrium – that is, where the debt, shares and assets held are bought or sold at their fair value, without the market having anticipated the decision.

1/ INCREASING DEBT

Suppose the shareholders of Holding plc decide to issue 20 additional bonds and use the proceeds to reduce the company’s equity by distributing an exceptional dividend. The overall exercise price corresponding to the redemption value of the debt at maturity is:

A look at the listed prices of the options shows us that at an exercise price of £3,200, Holding plc’s equity is valued as £31 × 100 shares = £3,100, indicating that the value of its debt at the same date is £219,900 (£223,000 − £3,100).

The new bondholders will thus pay £13,744 (20 bonds × £219,900/320 bonds), which will go to reduce the equity of Holding plc.

The shareholders consequently have £13,744 in cash and £3,100 in shares, i.e. a total of £16,844 compared with the previous £4,500. They have gained £12,344 to the detriment of the former creditors, who have seen the value of their claim fall from £218,500 to 300 bonds × £687.19, or £206,156.

Their loss (£218,500 − £206,156 = £12,344) exactly mirrors the shareholders’ gain. The implicit yield to maturity has risen to 13.3%, reflecting the fact that the borrowing has become riskier since it now finances a larger share of the same amount of operating assets.

Increasing the risk to creditors has enhanced the value of the shares, thereby reducing that of the bonds. The existing creditors have lost out because they were not able to anticipate the change in corporate structure and have been harmed by the dividend distribution.

Common (accounting) sense seems to indicate that distributing £13,744 in cash to shareholders should translate into an equivalent decrease in the value of their Holding plc shares. According to this reasoning, after the buy-back the Holding plc shares should have been revalued at −£9,244 (£4,500 − £13,744), but that cannot be!

Options theory solves this apparent paradox. It shows that when new debt is issued to reduce equity, the time value of the shares decreases less than the amount received by shareholders and remains positive. True, the likelihood that the value of Daughter plc shares will be higher than that of the redeemable debt upon maturity has lessened (since debt has increased), but it is still not nil, giving a time value that, while lower, is still positive.

Of course, this example is exaggerated. Such a decision would have catastrophic consequences for shareholders, who would be taken to court by the creditors and lose all credibility in the eyes of the market. But it effectively illustrates the contribution of options theory to equity valuations.

Increasing debt increases the value of shareholders’ investment, to the detriment of the claims held by existing creditors. Thus, value is transferred from creditors to shareholders.

Conversely, when debt is reduced by a capital increase, the overall value of shares does not increase by the value of the shares issued. The old debt, which has become less risky, has, in fact, “confiscated” some of the value, to the benefit of creditors and the detriment of shareholders.

2/ THE INVESTMENT DECISION

Now let us return to our initial scenario and assume that Holding plc manages to exchange the 100 shares of Daughter plc for 100 shares of a company with a higher risk profile called Risk plc, for £223,000 (100 × £2,230).

Each share of Holding plc is equal to a call option on a Risk plc share with an exercise price of £3,000 (300 × £1,000/100).

Suppose the value of a call option on a Risk plc share is £140 with an exercise price of £3,000 and an exercise date in three years’ time.

The Holding plc shares are consequently worth £14,000.

Exchanging a low-risk asset (Daughter plc) for a highly volatile asset (Risk plc) has redistributed value to the benefit of shareholders, whose gain is £9,500 (£14,000 − £4,500).

Their gain exactly mirrors an equivalent loss to creditors, since the value of the debt has fallen from £218,500 to £223,000 − £14,000 = £209,000, i.e. a £9,500 decline.

The higher risk led to an increase in the implicit yield to maturity of the bonds from 11.1% to 12.8%.

As in our previous examples, the transfer of value was only possible because creditors underestimated the power shareholders have over the company’s investment decisions.

3/ RENEGOTIATING THE TERMS OF DEBT

What if we now return to our initial situation and imagine that the company is able to reschedule its debt? This happens when creditors prefer to let a company in financial distress attempt a turnaround rather than precipitate its demise.

So let’s assume the debt is due in four years, rather than the initial three years. A look at our options price list for Daughter plc shares with a four-year maturity shows us that they carry a higher premium.

| Exercise price (£) | Value of put on Daughter plc shares in 4 years (£) |

|---|---|

| 2,600 | 140 (versus 130) |

| 2,800 | 89 (versus 80) |

| 3,000 | 53 (versus 45) |

| 3,200 | 40 (versus 31) |

This, of course, comes as no surprise to our attentive readers who remember learning in Chapter 23 that the value of an option increases with the length of its life.

The value of equity is thus £53 × 100 shares = £5,300. A bond is therefore worth £725.7 ((£223,000 − £5,300) / 300). Without having abandoned any flows, creditors’ generosity will have cost them £800.2

4/ OTHER PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

As our readers may have understood, shareholders’ equity is effectively only valued using the option models for distressed companies.

These theoretical developments have been the basis for the creation of models to assess the default risk of the firm. In particular, the consulting company KMV has developed well-known models from the work of Merton, Black and Scholes. Such models have been greatly developed by banks. The volatility of operating assets is a fundamental input to these models. As we have seen, a company with highly volatile operating assets has a high probability of bankruptcy. Unfortunately, volatility in the value of operating assets is not directly measurable in the markets. However, through the reasoning we have applied throughout this section, the market value of equity is used to determine the implied volatility of its operating asset.

Hedge funds have developed arbitrage strategies between debt and equity markets (capital structure arbitrage) based on this approach. These techniques use mainly credit default swaps (CDSs). Lastly, some borrowers hedge their credit risk by selling shares of the firm short. In doing so, they earn on one side what they may lose on the drop in value of their loan.

Section 34.4 RESOLVING CONFLICTS BETWEEN SHAREHOLDERS AND CREDITORS

Creditors have a number of means at their disposal to protect themselves and overcome the asymmetry from which they suffer. They can be grouped under two main headings:

- hybrid financial securities;

- restrictive covenants.

1/ HYBRID FINANCIAL SECURITIES

Hybrid financial securities, combining features of both debt and equity – such as convertible bonds, bonds with equity warrants, participating loan stock, hybrid bonds of indefinite maturity, etc. – would not be necessary in a perfect market.

In fact, should shareholders make investment or financing decisions that are detrimental to creditors, the latter can exercise their warrants or convert their bonds into shares, thus becoming shareholders themselves and, if all goes well, recouping in equity what they have lost in debt!

Jensen and Meckling (1976) have demonstrated that the issue of convertible bonds reduces the risk of the firm’s assets being replaced by more risky assets that increase volatility and thus the value of the shares. The same reasoning is applied when “free” warrants are granted to creditors who agree to waive some of their claims during a corporate restructuring plan (see Chapter 24).

2/ RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS

Covenants act like an atomic bomb, whose purpose lies in convincing shareholders not to take decisions that would result in transferring value from lenders to themselves. Like an atomic bomb, the aim is not to trigger it but rather to incite parties to negotiate.

In practice, when a company does not meet its covenants, banks generally agree either to grant a delay to restore the situation (covenant holiday) or to change the covenants to make them less constraining (covenant “reset”), in exchange for additional compensation (waiver fee) and/or an increased interest.

Covenants are analysed in more detail in Chapter 39.

Section 34.5 ANALYSING THE FIRM’S LIQUIDITY

In most cases, the company pays off part of its debt with its free cash flows and refinances the balance of its debt by taking out a new loan. Most of the time, the sum of free cash flows is higher than the amount of debt to be repaid, but the flows generally are further off in time than the due date for the debt, and can be insufficient in the short term. The duration (see Chapter 20) of cash flows is generally longer than the duration of debt flows, which rarely exceed six to seven years.

The firm is then exposed to a double risk:

- the risk of the interest rate at which it will refinance part of its current debt in the future;

- a liquidity risk since, at the time the firm has to take out a new loan, market conditions may not allow it to if there is a major liquidity crisis under way (as was the case in late 2008/early 2009).

It is possible to hedge against these two risks, as we shall see in Chapter 51. Frequently, however, the liquidity risk is unhedged, either because it is not always possible to hedge against it, or because the cost of hedging is seen as prohibitive, or possibly because severe liquidity crises are so rare that it is not deemed necessary to hedge against this risk.

The difference between the duration of a firm’s free cash flows and the duration of its debt (often a shorter period) constitutes an asset liability refinancing gap (ALRG). Aït-Mokhtar (2008) has shown that it is the same as a liability for a firm, as if it had entered into an interest rates swap (see Section 51.3) in which it pays the floating interest rate and receives the fixed rate. On maturity of its debt, the firm will only be able to make the repayment if it is able to find lenders that are prepared to lend to it, since the free cash flows it receives will be insufficient to pay off the whole of the debt. So, what it has done is undertaken to contract future debt at an unknown interest rate in order to continue its activity (hence the swap’s leg with a variable rate payment which corresponds to the interest rate of the future loan). In normal times, this liability is worth a negligible amount as it is reasonable to expect that a healthy firm will have no problems in refinancing in the future. But in the event of a liquidity crisis and for firms with imminent debt repayment deadlines (a few months or quarters), this ALRG has a very high value. It is equal to the existing uncertainty as to the possibility of the company being able to find the necessary financing.

So we can say:

Value of operating assets (i.e. enterprise value)

– Value of net debt

– Value of ALRG

= Value of equity capital

Which corresponds to:

When investors start to worry about the ability of the company to refinance in the near future, the value of the ALRG increases, pushing down the value of equity. And the phenomenon can pick up speed if the current lenders try and hedge their risks by selling short the firm’s shares, hoping to gain on this short-selling what they will lose as a result of the decline in the value of their debt.

When the firm is able to find refinancing for its debt, for example through a share issue, we see in some cases (Europcar in 2021) an increase in the share price, which contradicts what we have seen up to now. On the one hand, the value of the share is negatively impacted by the transfer of value to the creditors, but on the other hand, it benefits fully from the disappearance of the ALRG. And if the latter were worth more than the discount on the debt, the net impact would be positive and the value of the share would rise.

Section 34.6 CONCLUSION

The concept of time value for equity is the main added value of the application of option theory to corporate finance.

We are now quite far away from the simple book leverage effect that seemed to prove that shareholders could create value by investing funds at a higher rate than the interest rate. The relationship between shareholders and lenders is in practice quite different. Their interests can actually diverge significantly due to a change in the risk profile of the firm, even if there are no cash flow exchanges between them and the enterprise value remains constant.

We hope that our readers will have understood the importance of reasoning in value terms and now have the reflex of assessing any financial decision not only in terms of return, but also risk. The use of options may have been overwhelming. We hope so, as readers will now always remember to assess risk and value transfers in financial decisions.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

Chapter 35. WORKING OUT DETAILS: THE DESIGN OF THE CAPITAL STRUCTURE

Steering a course between Scylla and Charybdis

By way of conclusion to the part on capital structure policy, we would like to reflect once again on the thread that runs throughout this set of chapters: the choice of a source of financing.

We begin by restating for the reader an obvious truth that is too often forgotten: If the objective is value creation, then the choice of investments is much more important than the choice of capital structure. Because financial markets are liquid, situations of disequilibrium do not last. Arbitrage inevitably takes place to erase them. For this reason, it is very difficult to create value by issuing securities at a price higher than their value. In contrast, industrial markets are much more viscous. Regulatory, technological and other barriers make arbitrage – building a new plant, launching a rival product, and so on – far slower and harder to implement than on a financial market, where all it takes is a telephone call or an online order.

In other words, a company that has made investments at least as profitable as its providers of funds require will never have insurmountable financing problems. If need be, it can always restructure the liability side of its balance sheet and find new sources of funds. Inversely, a company whose assets are not sufficiently profitable will, sooner or later, have financing problems, even if it initially obtained financing on very favourable terms. How fast its financial position deteriorates will depend simply on the size of its debt.

Section 35.1 THE MAJOR CONCEPTS

1/ COST OF A SOURCE OF FINANCING

Several simple ideas can be stated in this context.

The required rate of return is basically independent of the method of financing and the nationality of the investor. It depends solely on the market risk of the investment itself.

This presents the following consequences:

- it is generally not possible to link the financing to the investment;

- no “portfolio effect” can reduce this cost;

- only the bearing of systematic risk will be rewarded.

It is therefore short-sighted to choose a source of financing based on what it appears to cost. To do so is to forget that all sources of financing will cost the same, given the risk.

We have too often heard it said that the cost of a capital increase was low, because the dividend yield on the shares was low, that internal financing costs nothing, that convertible bonds can lower a company’s cost of financing, and so on. Statements of this kind confuse the accounting cost with the true financial cost.

A source of financing is a bargain only if, for whatever reason, it brings in more than its market value. A convertible bond can be a good deal for the issuer not because it carries a low coupon rate, but only if the option embedded in it can fetch more than its market value.

Let us dwell briefly on the error one commits by confusing apparent cost and true financial cost.

- The difference is minor for debt. It may arise from changes in market interest rates or, more rarely, from changes in default risk. In matters of financial organisation, debt has the merit that its accounting cost is close to its true cost; furthermore, that cost is visible on the books, since interest payments are an accounting expense.

- The error is greater for equity, inasmuch as the dividend yield on the share needs to be augmented for prospective growth in dividends.

- The error is extreme for internal financing, where, as we have seen and will see in Chapter 36, the apparent cost of reinvested cash flow is nil.

- The error is hard to evaluate for all forms of hybrid securities – and this is often the explanation for their success. But let the reader beware: the fact that such securities carry low yields does not mean their financial cost is low. As we have shown in the foregoing chapters, an analysis of the hybrid security using both present value and option valuation techniques is needed to identify the true cost of this financing source.

Debt, by virtue of the liability that it represents for timely payments of interest and principal, has a direct consequence on the company’s cash flow. Debt can plunge the company into the ditch if it runs into difficulties; on the other hand, it can turn out to be a turbocharger that enables the company to take off at high speed if it is successful.

| Source | Instrument | Theoretical cost to be used in investment valuation | Cost according to financial theory (A) | Apparent or explicit cost (accountability, cash flow) (B) | Difference (A) – (B) | Determinants of the difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debt | Market rate at which the company can refinance | Nominal rate | Small | Evolution of market interest rates; evolution of default risk | ||

| Equity | Share issue | Expected return required by the market on shares with the same risk profile | Nil in income statement; apparent cost measured by the dividend yield | Significant | Expected dividend growth rate | |

| Self-financing | The same for all products, it is a function of the systematic (non-diversifiable) risk of the investment being analysed | Expected return required by the market on shares with the same risk profile | Nil in the income statement; no apparent cost | Very significant | Total absence of apparent cost | |

| Hybrid products | Convertible bonds, Bonds with warrants attached | Yield to maturity + value of the conversion option | Nominal interest rate (partially restated according to IFRS) | Medium | Value of conversion option | |

| Preference shares | Return should be slightly lower than the ordinary shares | Higher than ordinary shares and fixed throughout the life of the instrument | Small | They are shares for which a part of the value is guaranteed (present value of fixed dividends) | ||

| Hybrid bond | Rate higher than the cost of a plain vanilla debt | Nominal interest rate | Difficult to evaluate | Variability used for the subordination clause |

If a company is successful, the cost of a share issue will appear to be much higher, as the company will pay out much higher dividends than they initially expected. They will notice, looking backwards, that the issuance price of the share was very cheap. On the contrary, if the firm is in financial distress, the cost of the share issue will be close to nil, as the company will not be able to pay the expected dividends. The same is rarely true for debt, as it only occurs if the firm’s financial distress leads debtholders to forgive part of their loans.

2/ IS THERE A “ONCE-AND-FOR-ALL” OPTIMAL CAPITAL STRUCTURE?

The answer is clear: no, the optimal capital structure is a firm-specific policy and changes across time.

At the same time, there are a few loose ideas on the subject that the reader will have absorbed. Otherwise, how could one explain why the notion of what constitutes a “good” or “balanced” capital structure should have “changed” so much, and so often, over the course of time?

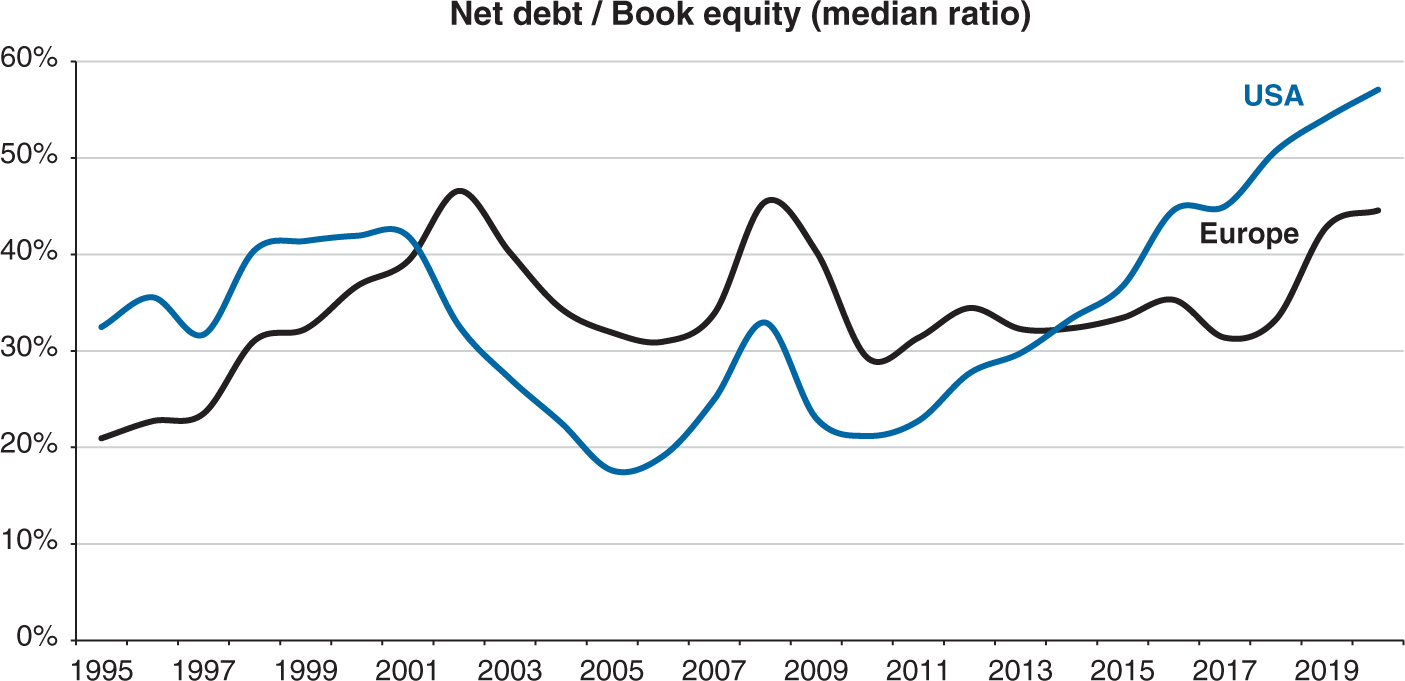

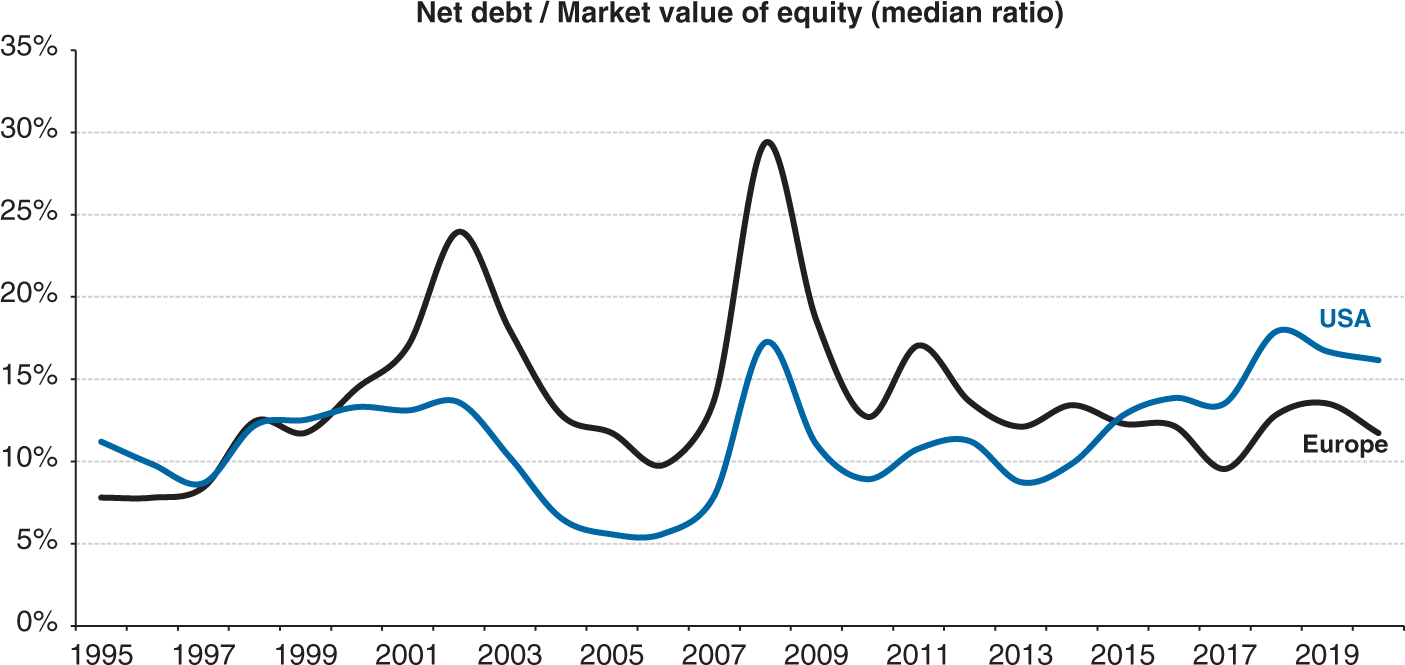

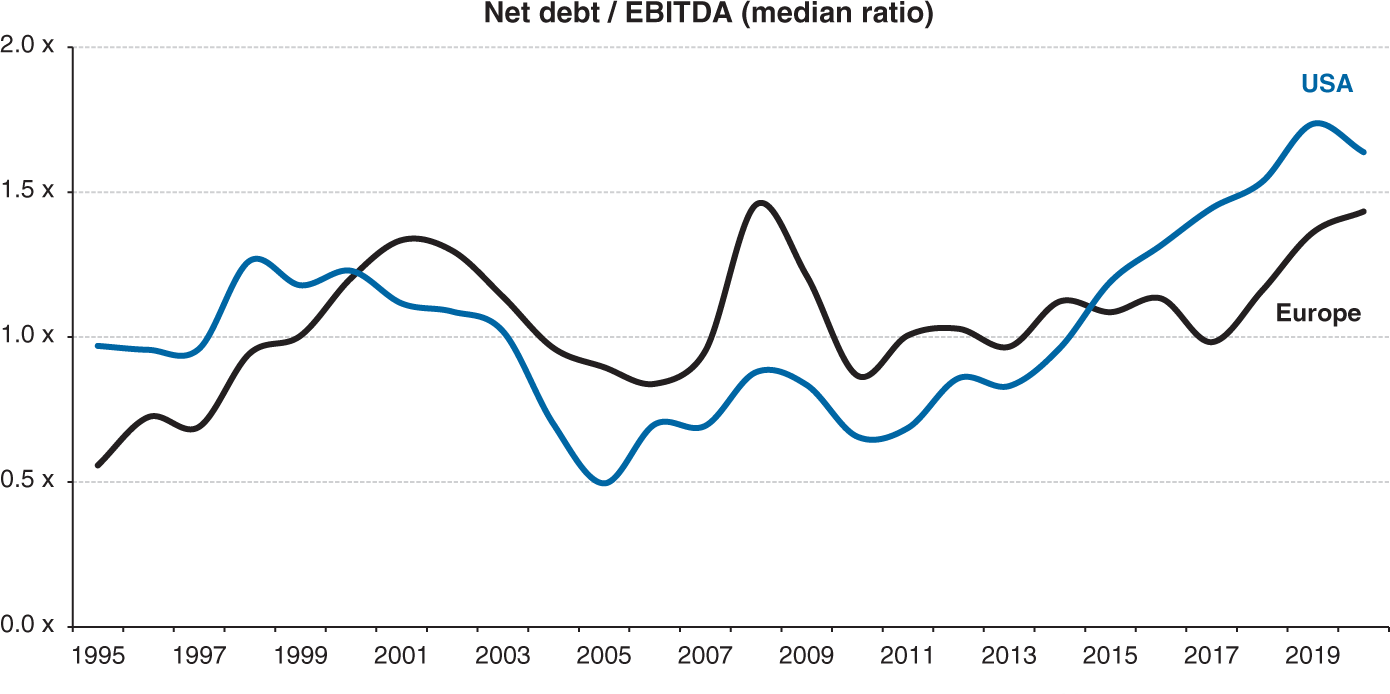

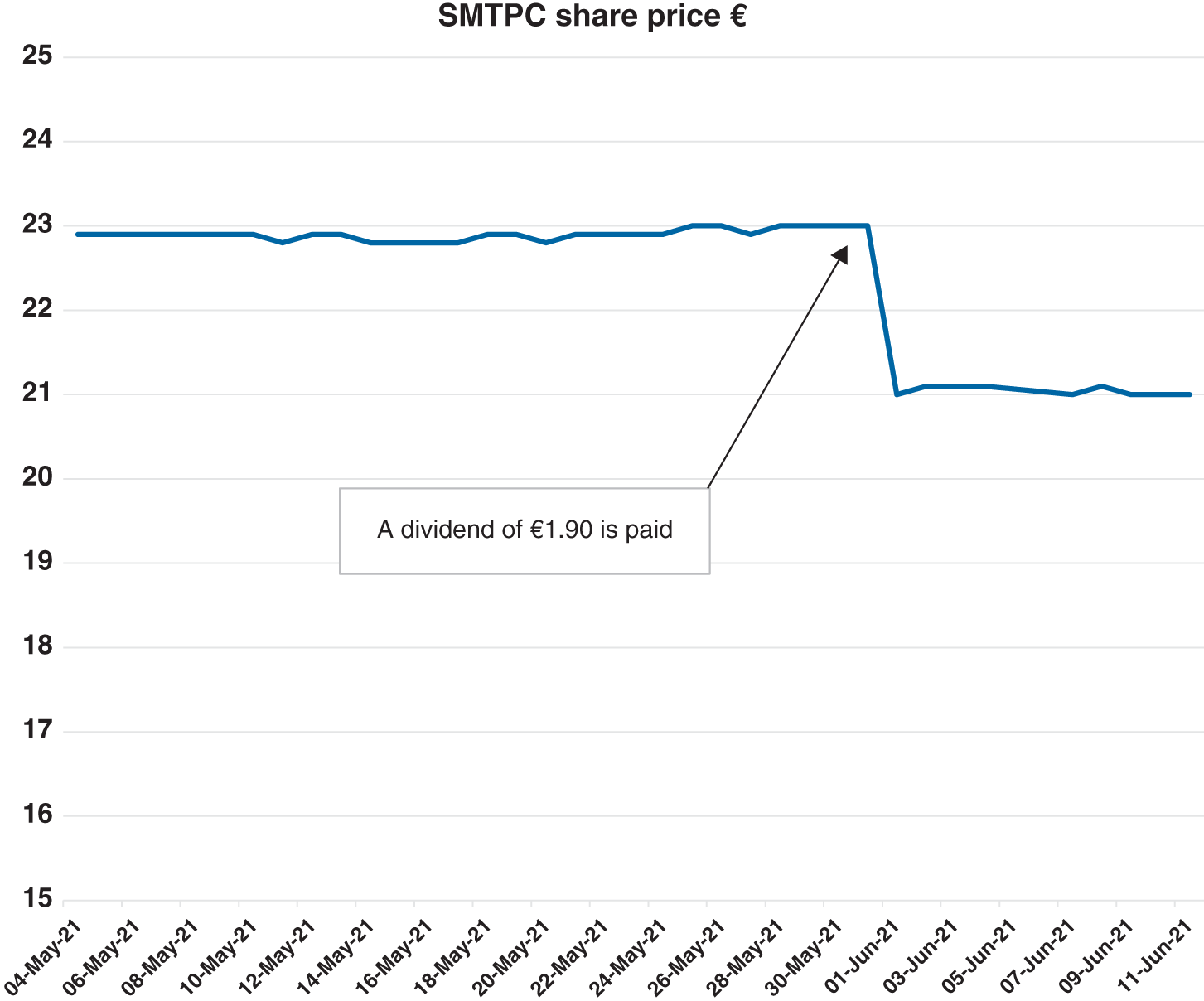

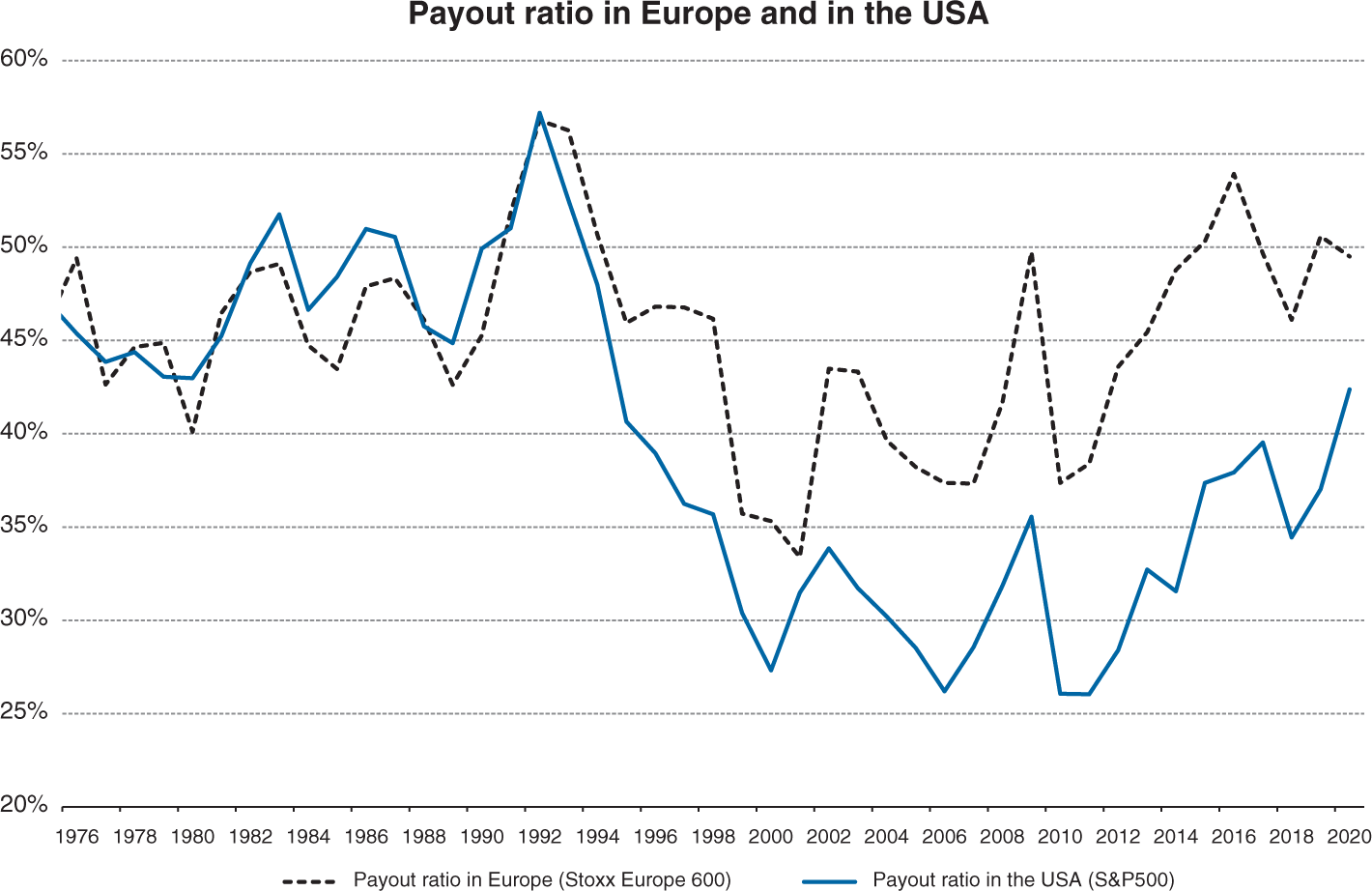

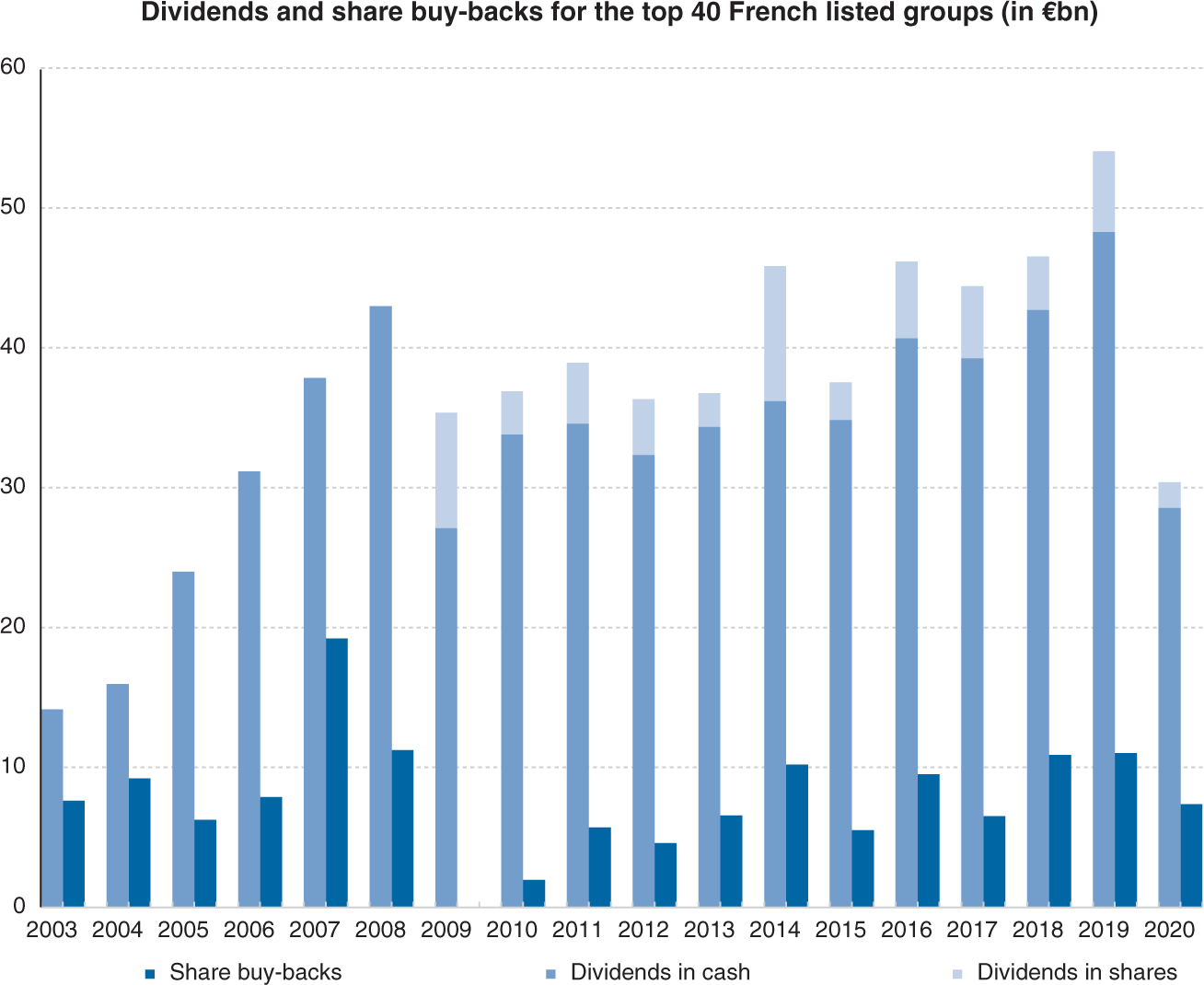

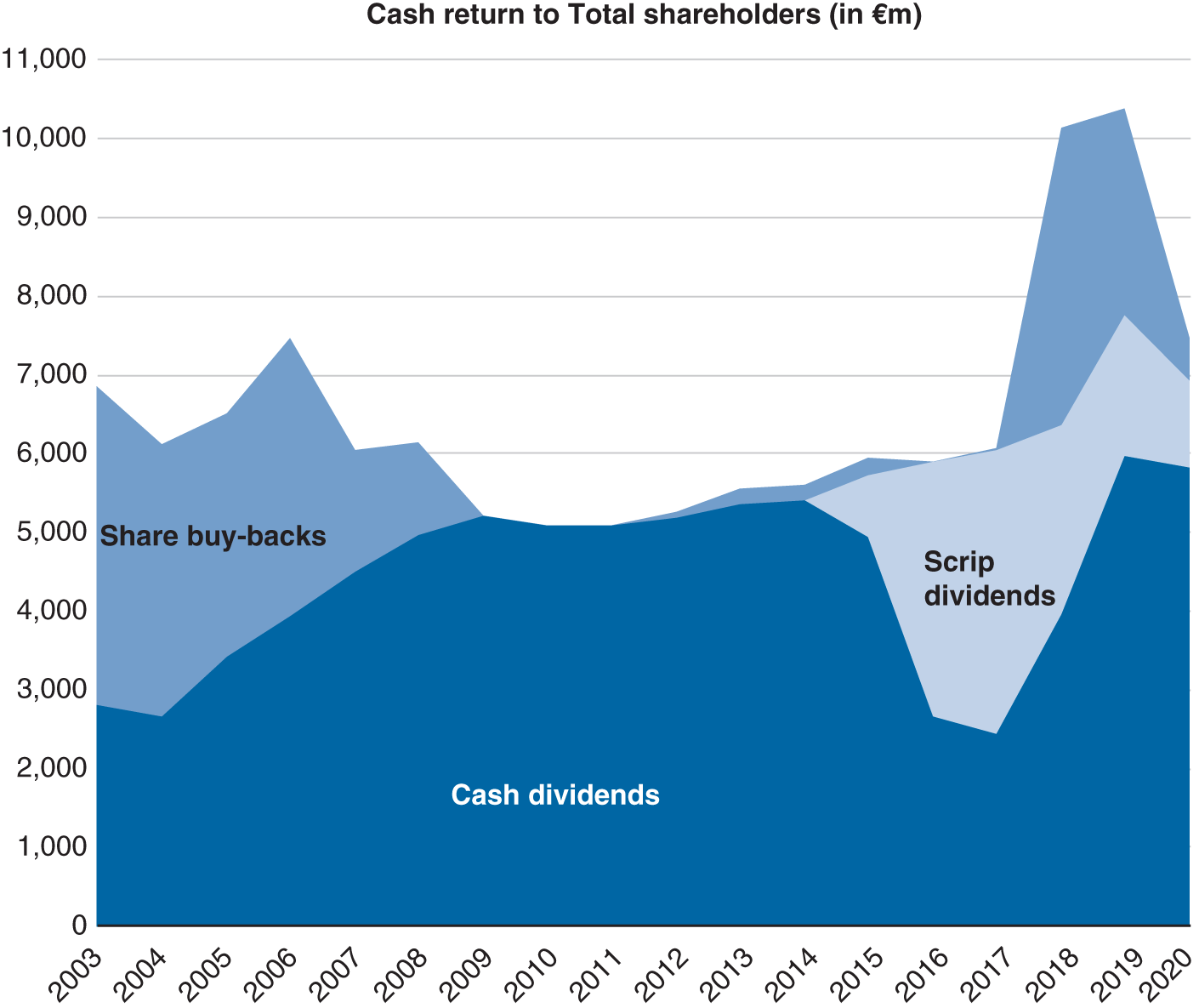

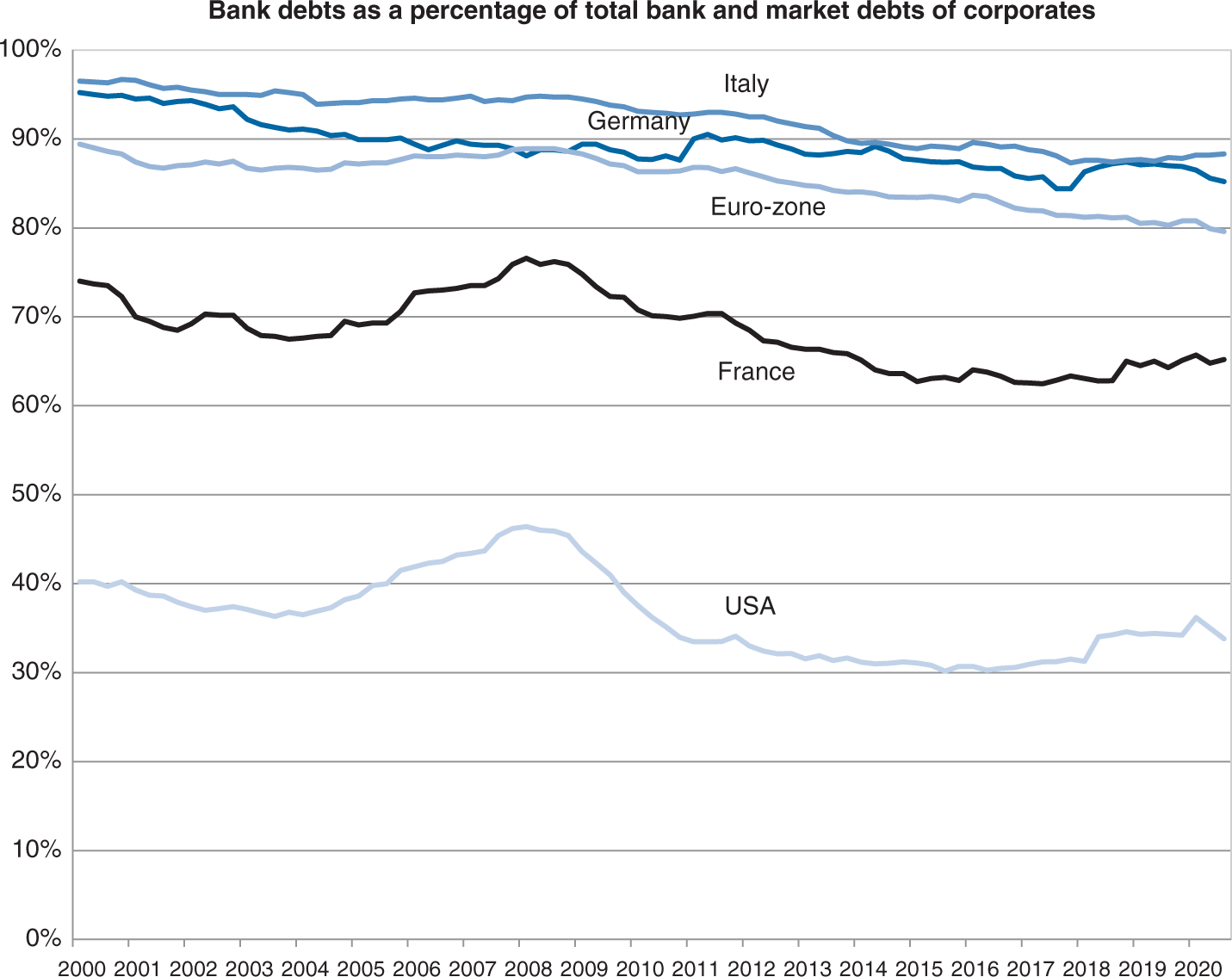

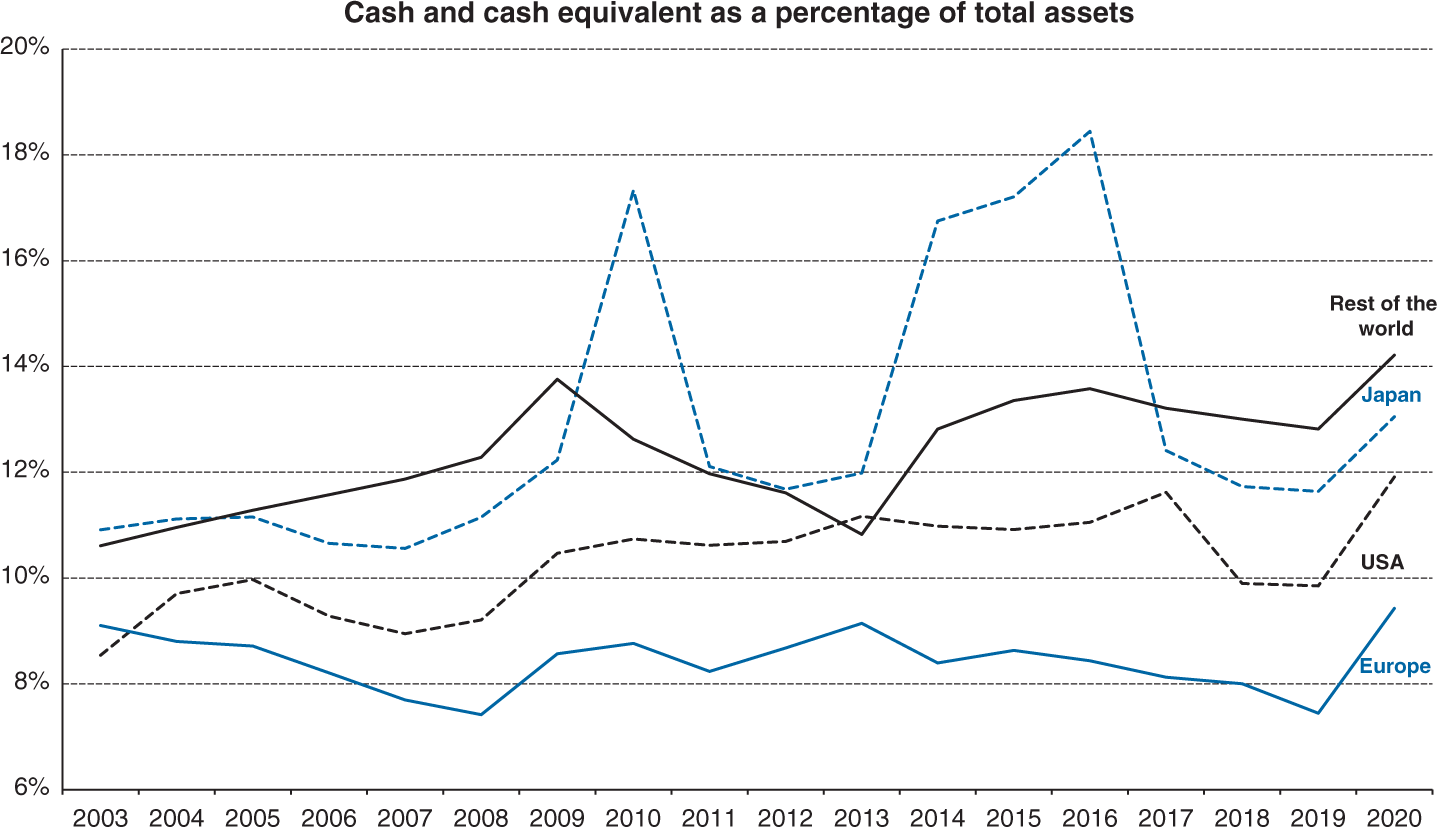

Source: Data from Factset‐ Eurostoxx 600 et S&P 500

- In the 1980s, a good capital structure was characterised by gradual diminution of debt, improved profitability and heightened reliance on internal financing.

- In the early 1990s, in an environment of low investment and high real interest rates, there was no longer a choice: being in debt was not an option. Share buy-backs appear in Europe.

- In the late 1990s, though, debt was back in favour if used either to finance acquisitions or to reduce equity. The reason: nominal interest rates were at their lowest level in 30 years.

- The 2000s started with a financial crisis (the bursting of the Internet bubble) followed by an economic crisis that led to a closure of financial markets. This prevented firms from rebalancing their financial structure towards more equity. The lesson was learnt, as when the second economic crisis of the decade arrived in 2007–2008, corporates were lowly geared, except for groups involved in leveraged buyouts who suffered first. In all sectors, firms were trying to lower their debt level (by lowering capex and reducing working capital) to maintain flexibility as the timing of the upturn remained uncertain.

- In the middle of the 2010s, companies that built up cash reserves resumed share buy-back operations or distributed large dividends, sometimes even going back to external growth operations.

- With the Covid-19 crisis in 2020 forcing companies to react very quickly, losses from confinements are financed in the first instance by available cash or debt, which weighs on the financial structure in many sectors. Share issues will certainly come at a later stage.

Source: Data from Factset‐ Eurostoxx 600 et S&P 500

Source: Data from Factset‐ Eurostoxx 600 et S&P 500

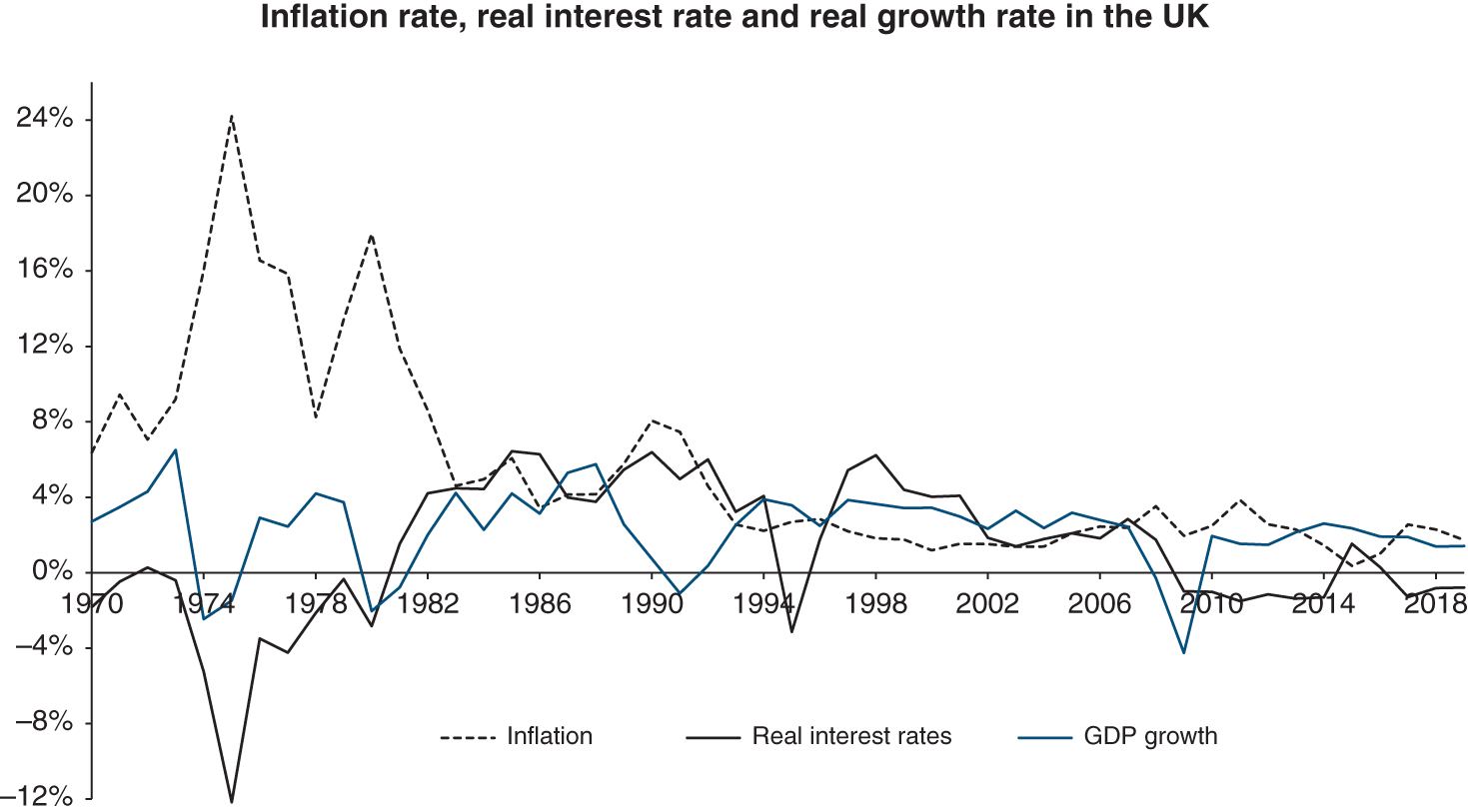

3/ CAPITAL STRUCTURE, INFLATION AND GROWTH

Because inflation is always a disequilibrium phenomenon, it is quite difficult to analyse from a financial standpoint. We can observe, however, that during a period of inflation, of high-volume growth, and negative real interest rates, overinvestment and excessive borrowing lead to a general degradation of capital structures. For companies that invest and reap the benefit of inflated profits, adjusted for inflation, their cost of financing is low. Shareholders can benefit from this phenomenon as well: a low rate of return on investment will be offset by the low cost of financing. Chinese groups in the early 2000s are proof of this.

Source: Data from Factset ‐ Eurostoxx 600 and S&P 500