**Section V FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT

****PART ONE. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND FINANCIAL ENGINEERING

In this part, we will examine the issues an investment banker deals with on a daily basis when assisting a company in its strategic decisions, which include:

- organising a group;

- launching an IPO (initial public offering);

- selling assets, a subsidiary or the company;

- merging or demerging;

- restructuring and more.

We do hope that our readers will not spend whole nights on these topics, unlike investment bankers!

This section also sets out some ideas on the financing of start-ups. This might not be what investment bankers like doing most, unless they have to reinvent themselves as an entrepreneur, investor, or business angel!

As you will soon realise, financial engineering raises and solves many questions of corporate governance.

Chapter 40. SETTING UP A COMPANY AND FINANCING START-UPS

A really big adventure!

All groups were once upon a time start-ups, and some were even set up in such improbable places as a maid’s room (NRJ), a garage (HP) or a university dormitory (Facebook). The most talented of entrepreneurs, the luckiest, the hardest working, with the ability to learn from failures and with vision, will succeed in creating a group that survives, but the vast majority will fail. Fortunately, this fact does not prevent new entrepreneurs, every year, from embarking on this adventure. We’ve written this chapter for them so that they can avoid making bad financial choices that could put their entrepreneurial adventure in danger. As for anyone else who reads it, we hope that we’ll have sown a tiny seed which perhaps one day will grow into something bigger.

Section 40.1 FINANCIAL PARTICULARITIES OF THE COMPANY BEING SET UP

In our view, there are five:

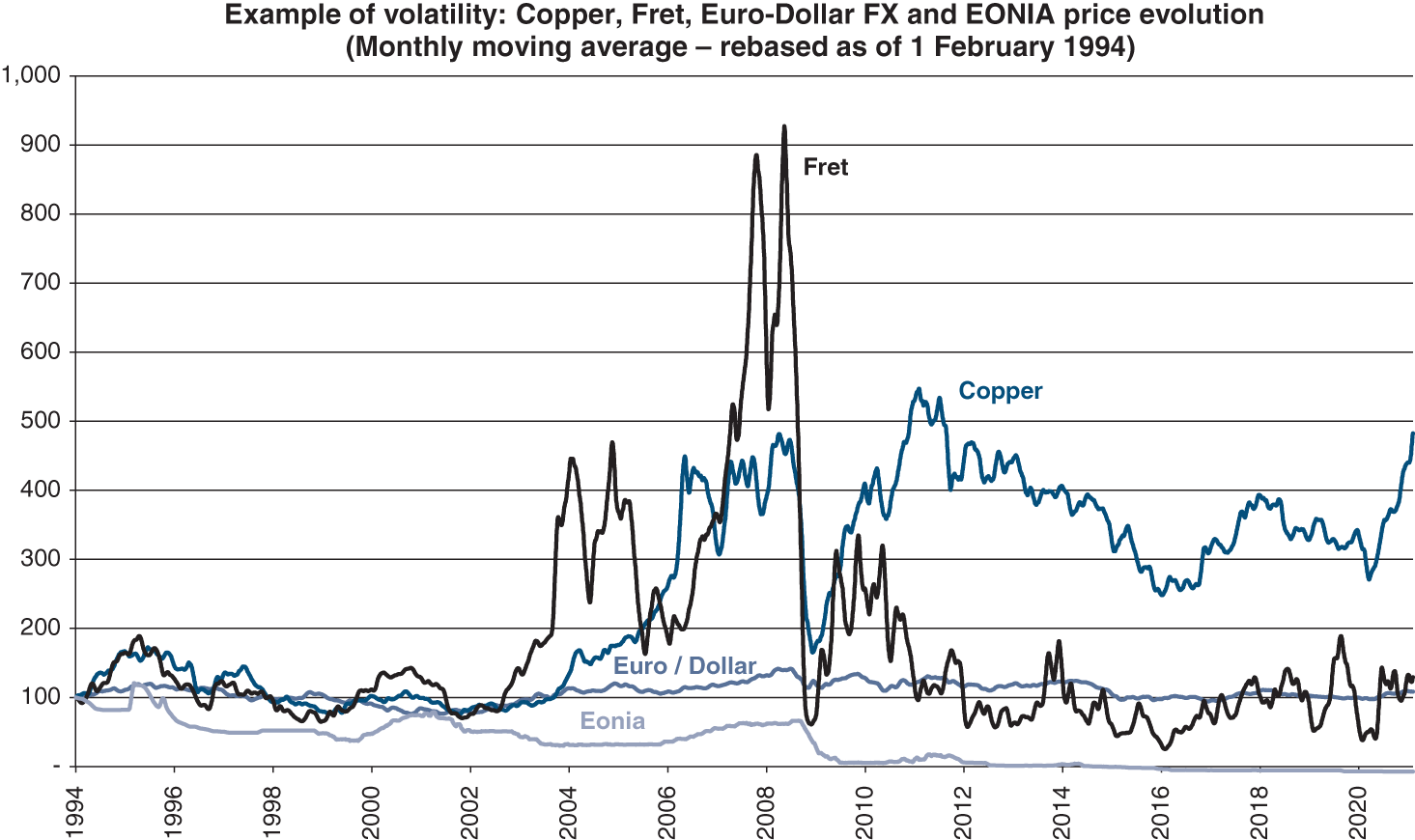

1/ THE EXTREME VOLATILITY OF CAPITAL EMPLOYED, WHICH MEANS VERY HIGH RISK

Many entrepreneurs1 who launch businesses have an idea or a product or a service but do not yet have an economic model that would enable them to cover their costs and get a reasonable return on their capital invested. When Larry Page and Sergey Brin developed their algorithms that were to give rise to Google, their aim was to come up with a more efficient search engine than those already in existence. They were not sure that they would succeed and they had no idea of how they could make this tool pay. It was only some years later that the idea of associating advertising with searches was born, resulting in a particularly efficient economic model.

This fundamental uncertainty about the relevance of a concept and the ability to find a money-earning demand for it is not specific to the Internet sector. The same situation can be found in the fields of biotechnology, industrial innovation and new services, as well as in commerce.

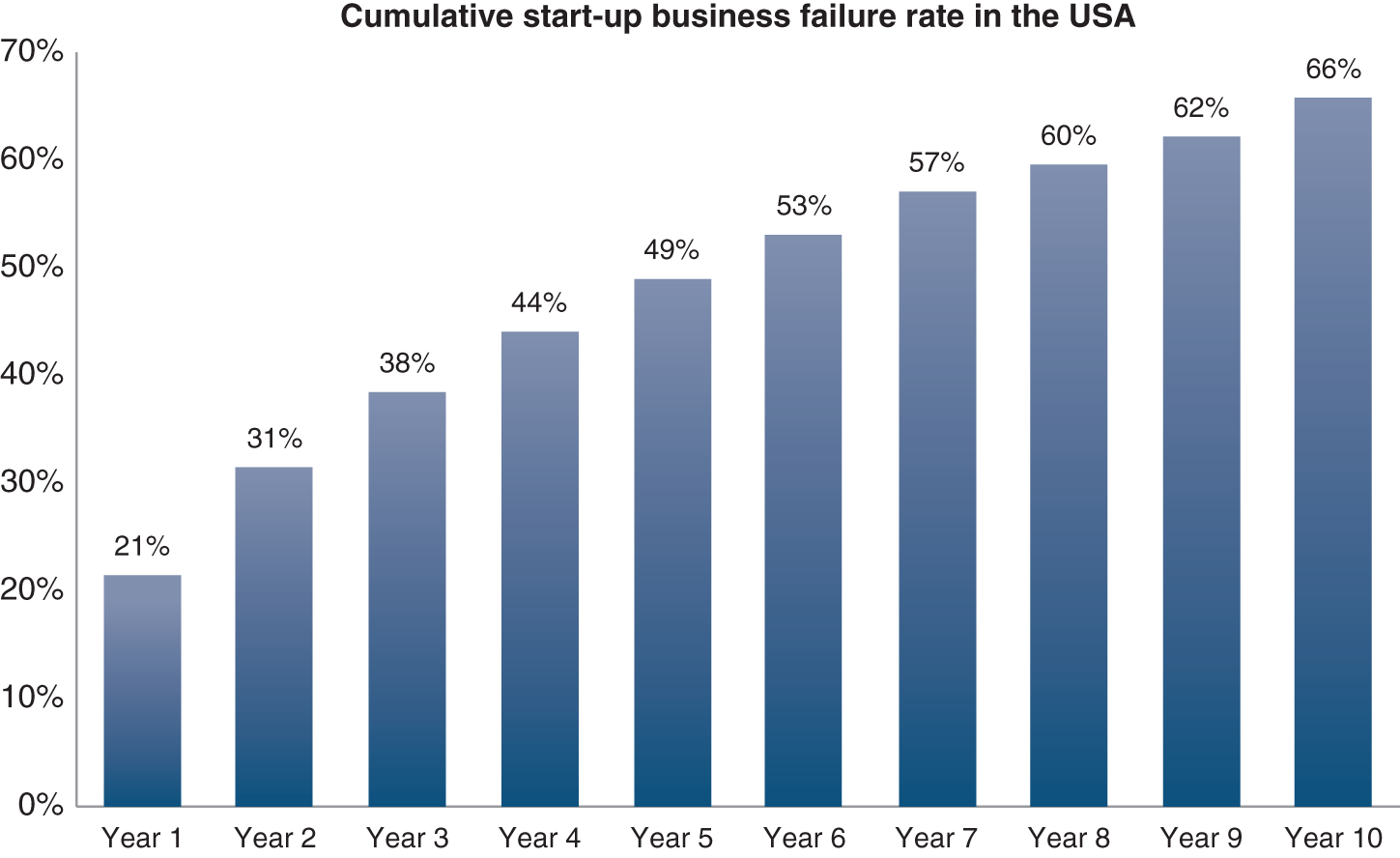

This is the reason why only 34% of companies created in the US survive 10 years after their inception.

Source: Business Employment Dynamics Report, Bureau of Labor, 2021

Far from being linear, the development of a start-up2 goes through successive stages, which are all possible occasions for failure and/or a change in direction. An entrepreneur has an idea. Will they be able to raise the funds necessary for creating the prototype? If so, will it be possible to create functions that will give the product a competitive advantage? If so, will the entrepreneur find customers prepared to acquire the product at a price that more than covers costs? If so, will it be possible to shift to a mass-production phase without losing the quality of the prototype? If so, etc.

A “no” does not necessarily mean the end of the story, but perhaps a departure in a new direction after specific corrections have been made, or possibly having to go back to the drawing board. So new entrepreneurs have to be psychologically strong and have solid finances!

2/ THE CRUCIAL ROLE OF THE FOUNDER

An enterprise is often set up by one person (Marcel Dassault, Elon Musk, Richard Branson) or a small group of individuals who personally bear a very high level of risk, giving up a situation in which they are well established or renouncing the possibility of such a situation, for what for many of them will in the end turn out to be nothing more than a pipe dream. But they bring a project, a vision and a charisma that is indispensable for facing the unknown, adversity and challenges, and indispensable for convincing others (employees, investors) to follow them. Without the founder, the company would simply not exist.

From a financial point of view, a person starting up a company is the polar opposite of the ideal investor described by the CAPM in Chapter 19. The entrepreneur focuses on a single asset and takes all of the risks. The concept of diversification means nothing to them – it is all or nothing. They have a tiny chance of taking home the big prize and a huge risk of losing everything. But the entrepreneur does not reason in terms of probability like the financial manager does. Their aim is not financial (personal enrichment), but rather, and above all, humanistic (to create). They live in a completely different world.

The entrepreneur generally feels very passionate about their company – it is their creation – which is a far cry from the cold detachment of the financial manager for whom everything is just a question of risk and return. As we will see, this character trait of the entrepreneur is not without danger when their desire to control pushes them to take on too much debt or to put the brakes on the company’s growth.

3/ THE NEED FOR EXTERNAL FINANCING

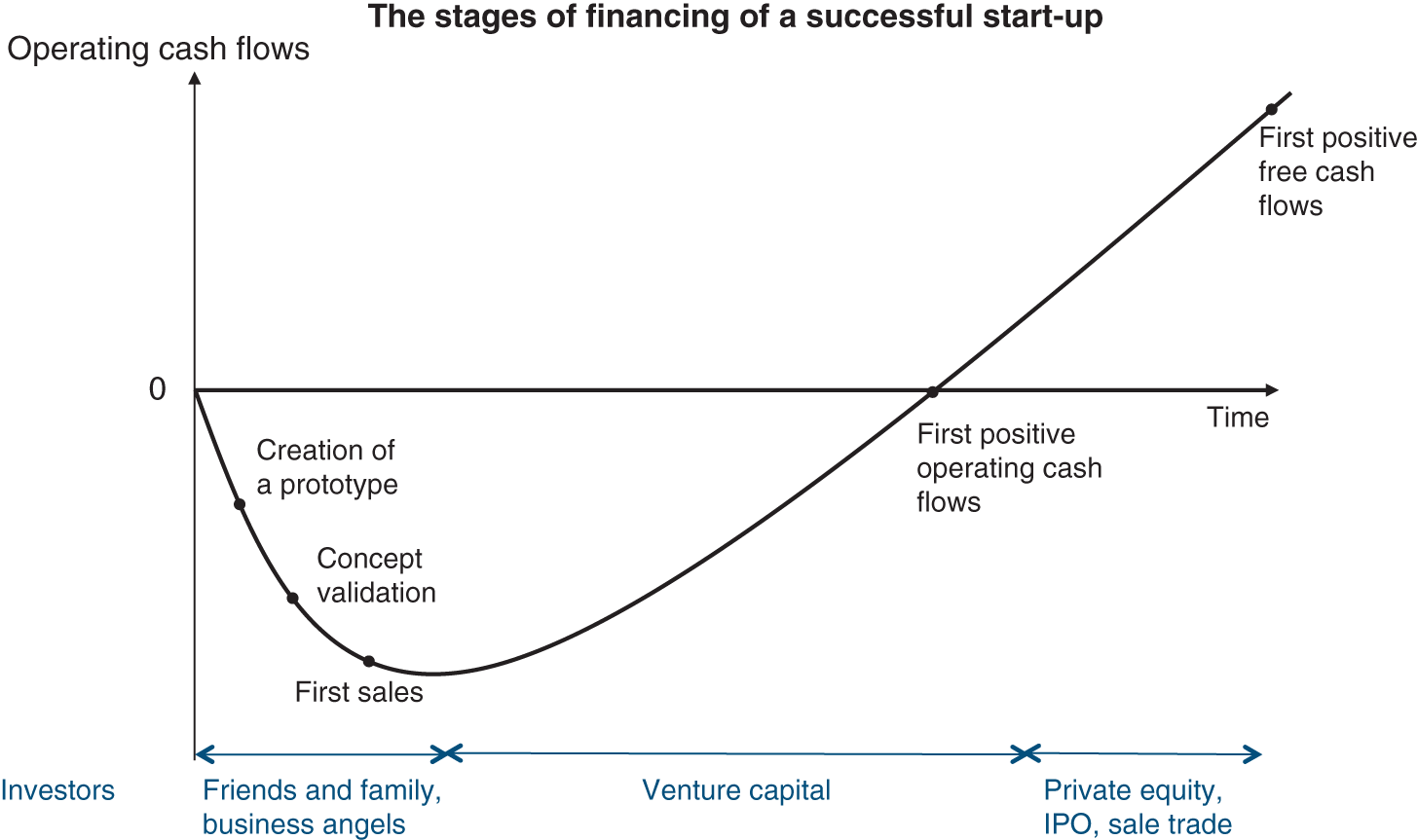

Very few start-ups immediately generate positive cash flow. Most often, they initially make losses and some have to wait several years before they are able to record their first euro of sales. And when they do start recording positive earnings, investments (in fixed assets and working capital) are rarely fully covered by cash flows.

Since their free cash flow is negative, it is imperative that they find external financing, as generally the entrepreneur does not have sufficient assets to finance their adventure on their own.

4/ A MORE ACTIVE ROLE FOR INVESTORS

Investors hope that they have invested in the next unicorn (valuation greater than $1bn), centaur (valuation greater than $100m), or at the very least pony (valuation greater than $10m), while remaining aware that out of 10 investments that they make, seven to eight will yield nothing, one or two will earn a reasonable return and the tenth could earn 10 or 100 times the investment, saving all of the rest.

According to Cambridge Associates, the post-fee IRR of US venture capital funds is between 10 to 15% per year. Funds created in 2009 yield 20% in the upper quartile and only 5% in the lower quartile. The standard deviation is 12%.

Given that they are taking very high risks, they will monitor their investments very closely, providing the entrepreneur with advice and contacts to help steer the company in the right direction. The entrepreneur is very much in favour of a high level of involvement by investors as they bring what the entrepreneur lacks – experience, contacts, distance, advice on taking difficult decisions and … capital. The loneliness of the entrepreneur is not a myth.

Since the company will raise funds several times before it succeeds in generating positive cash flows, investors have every interest in ensuring that the company follows its road map so as to be able to form an opinion before it takes any decision to reinvest. Their close involvement alongside the manager is thus not disinterested. It is made a lot easier by the fact that, generally, there are not very many of them.

5/ A HIGHLY SPECULATIVE VALUATION WHICH IS THUS VOLATILE

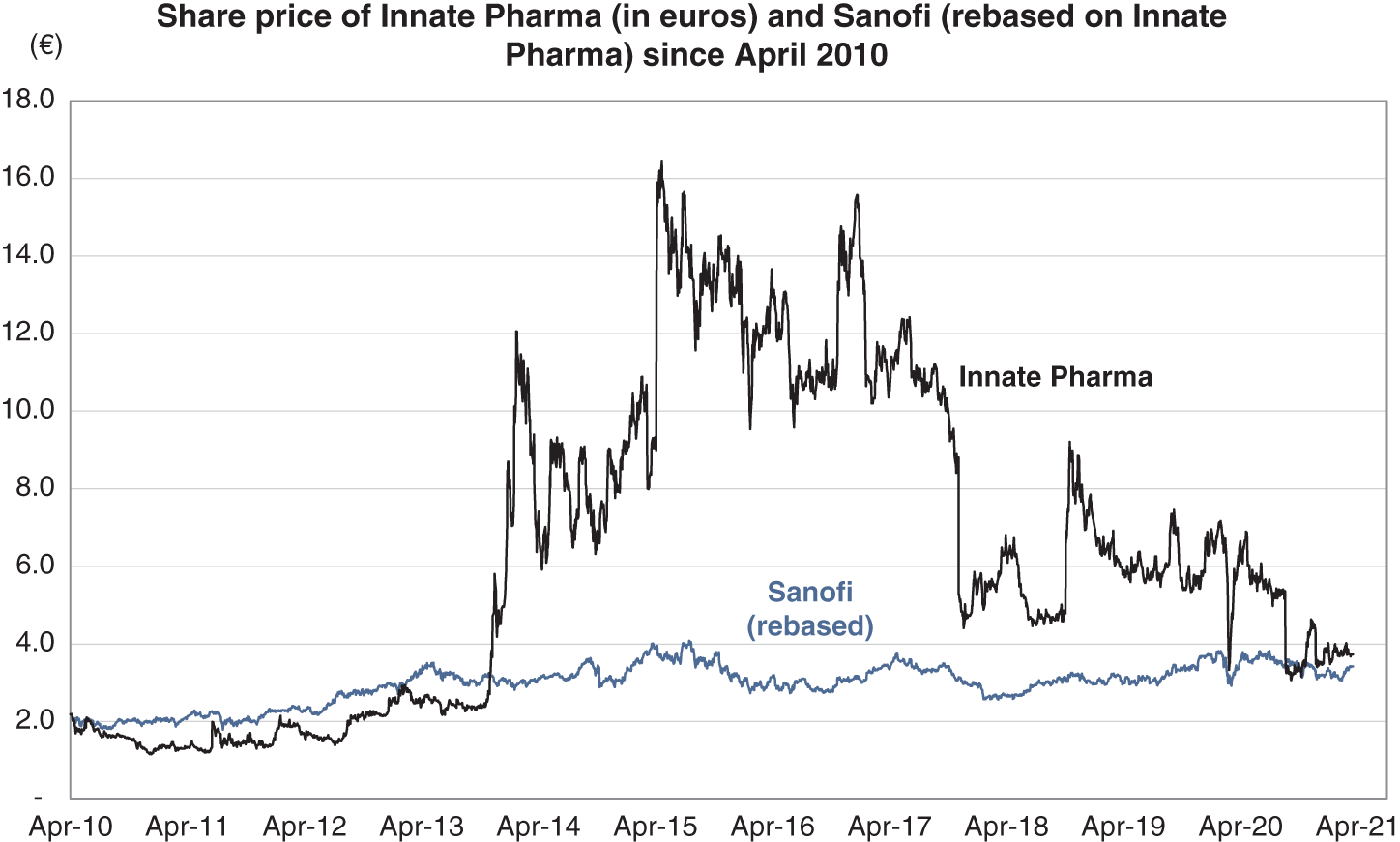

Unsurprisingly, the extreme volatility of capital employed can be seen in the share price, even without the leverage effect, with very sharp share price variations. These variations are the sign of high risk that is specific to this stage of the company’s development. This is illustrated by the share price performances of Innate Pharma, a biotechnology start-up, and Sanofi, one of the world leaders in the pharmaceutical sector.

Source: Euronext

The sudden changes in Innate Pharma’s share price indicate disappointing results or breakthroughs in its medical research programme.

Section 40.2 SOME BASIC PRINCIPLES FOR FINANCING A START-UP

1/ EQUITY CAPITAL, MORE EQUITY CAPITAL AND EVEN MORE EQUITY CAPITAL

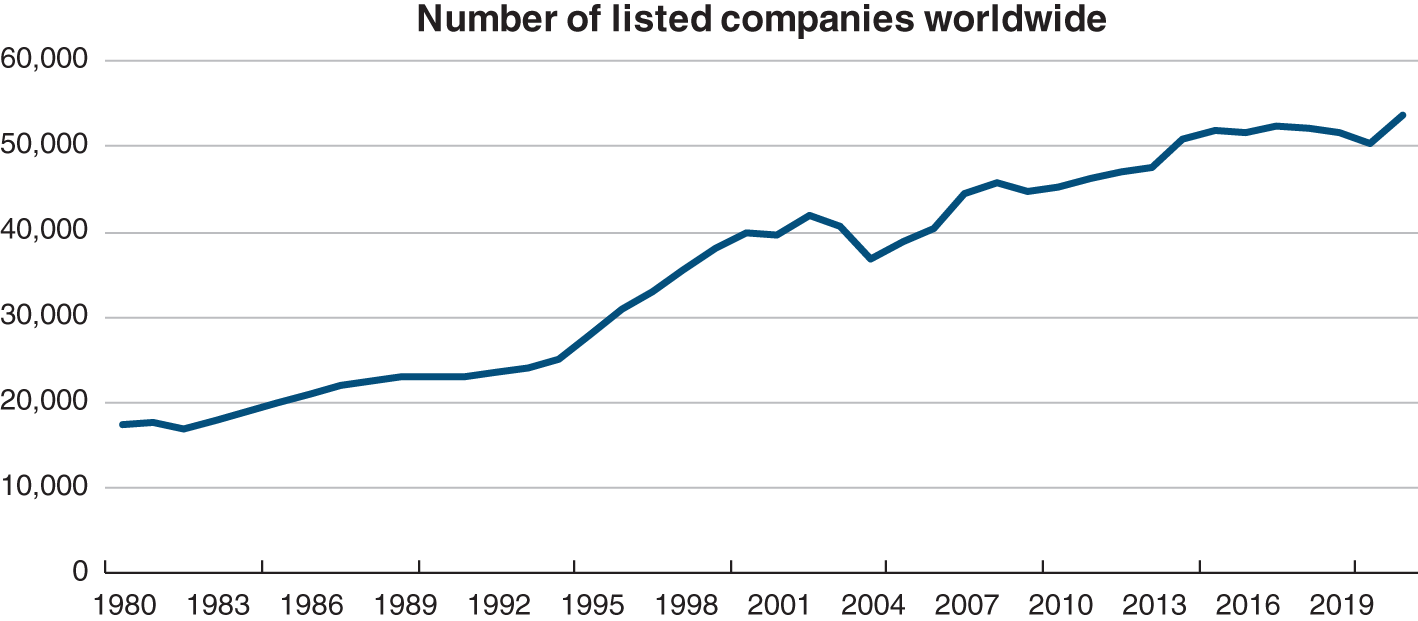

When the economic model of the company is not clearly established and its exploitation does not require assets to be held which have a value that is independent of the activity (real estate, commercial lease), the only reasonable way for a company to finance itself is with equity capital.

Debt, because of the regular payment of interest and the repayment of capital, is quite unsuitable when cash flow is unpredictable and negative over an undetermined period. Entrepreneurs need time to test their products or services, correct errors, make adaptations in line with feedback from the first customers, drop 80% of what’s been done if necessary and head off in another direction. Entrepreneurs are completely wrapped up in their adventures and cannot allow themselves to be distracted or have their timeframes dictated by debt, ticking away like a time bomb.

We have seen too many talented entrepreneurs seeking to avoid being diluted in the capital of their companies by issuing too much debt too early. At this stage of the company’s development, the challenge is not to avoid dilution or to minimise it, but to demonstrate that the company is viable. Better to have a small stake in a company that has had the time it needs to prove that it is viable, than a large stake in a company that is heading for bankruptcy or whose liabilities have to be restructured, as in this case the entrepreneur dilution will be massive.

We cannot stress this point enough.

Once the economic model has been found and its viability has been more or less assured, the company can then take out debt.

It is only if the start-up uses assets whose value is independent of its activity – such as vehicles or equipment with a secondary market – that it can finance them partially using debt. This is the case in sectors like retail, transport and restaurants where business models are proven. The initial investment is often higher than in the Internet or personal services sectors. Debt then makes it possible to get sufficient financing together, which would be difficult using only equity. If this is the case, it should be as long-term as possible, ideally through a leasing agreement so as to avoid putting pressure on the entrepreneur.

This can also be the case for a company that needs to finance a large working capital for its growth. Thus, the use of factoring or discounting of receivables can enable a start-up to finance its growth.

2/ ONE OR SEVERAL ROUNDS OF FINANCING?

Between 1999 and 2020, Innate Pharma, the biotechnology start-up mentioned above, raised €305m in equity from venture capital funds or the public (it has been listed since 2006) in ten capital increases. One every two years. Wouldn’t it have been simpler to carry out a single capital increase of €305m in 1999, thus giving the company peace of mind with regard to its financing?

No. This would not have been in the interests of either the investors or the entrepreneur.

The former because they are reluctant to give the entrepreneur a blank cheque and will only give the financial resources necessary for getting to the next step of the entrepreneurial adventure: development of a prototype, opening and operation for a few months of the first store, reaching 100,000 members for a social network, etc. If the step is successfully reached, a new round of financing will be organised with the same investors and/or new ones, giving the company the financial resources necessary for reaching the next step. Here again, investors will most often only consider committing to a new round of financing if this new step is reached.

If the next step is not reached, investors will step in and decide whether any corrective measures introduced by the entrepreneur look like they are sufficiently solid to warrant continuing the adventure in this new direction and participating in a new (last?) round of financing. If not, the adventure will probably stop there.

This system using several rounds of financing enables investors to control the entrepreneur, to resolve potential conflicts of interest and to allocate their funds to the most promising projects. The interest for entrepreneurs, after an initial failure, is to persevere, come what may, as long as the funds that are being used are not being provided by them. The fear for investors would be that entrepreneurs get themselves into more and more difficulties, wasting funds that could be better used on other projects run by other teams. Here we can see the mechanisms of agency theory, discussed in Chapter 26.

For the entrepreneur, massive fundraising for forecasted financing requirements over several years of activities is not a panacea either. As the company has not yet proved anything – or very little – the issue price of shares is likely to be very low and the entrepreneur will be significantly diluted. On the other hand, in a succession of financing rounds, since each one marks the success of a step, the entrepreneur and the investors in the previous rounds will be in a good position to negotiate a higher share price at each round, thus limiting the dilution of the shareholders and also the entrepreneur.

3/ GOODWILL AT THE START OR AT THE EXIT?

Goodwill is the difference between the value of equity and the amount of equity invested. Its conceptual basis is the ability of the firm to generate, over a certain period, returns that are higher than those required by investors, given the risk (see Chapter 31).

The entrepreneur often considers that they are contributing the idea, the ability to implement the idea, and funds (although not a lot). Investors, for their part, only contribute funds. Accordingly, it will only seem logical to the entrepreneur to receive better treatment than the investors when shares and voting rights are being allocated, enabling them to retain a majority of voting rights in the project. This is why often, during the first round of financing, there is a higher issue price for shares for investors than for the founders. The difference is often considerable, especially if there is a lot of buzz around this new company. We’ve seen investors pay 100 times more for their shares than the entrepreneurs, which is a lot for a company that has yet to prove itself!

This practice is not without danger. As soon as the emerging company, after a few quarters of activity, is unable to stick to its roadmap and fails to meet its first targets, the question of a second round of financing is raised very quickly, while the funds raised in the first round are in the process of being totally depleted.

The relationship between the entrepreneur and the investors could deteriorate rapidly. The investors have made a capital loss because of the entrepreneur who has not delivered what was promised in the business plan, while the entrepreneur has made a capital gain thanks to the goodwill paid by the investors, who discover that there was no real foundation for this goodwill. Although all of the shareholders will have to get together to study how to get things back on track, and to correct or call into question all or part of the strategy implemented until now, there is the risk that any such meeting will be marred by a poisonous atmosphere. This can result in a deadlock at a time when it is vital that things keep moving.

The initial investors, unhappy with the situation, will then find it very difficult to agree to participate in a second round of financing, even though the subscription of new shares will enable them to lower the average cost price of their shares. They often prefer to accept their losses and dilution and move on to other opportunities, rather than go back to their investment committees to explain that they were wrong the previous time about the relevance of the concept and the price paid, but that this time, they’re right, even though the entrepreneur has just acknowledged a first failure. We are now no longer in the realm of pure rationality but have moved into the realm of behavioural finance! (See Section 15.6.)

Since our entrepreneur probably doesn’t have the resources to finance the new direction of the company, new investors will have to be found. The task of convincing them will be particularly arduous, as the signal sent by the failure of the initial investors to participate in this new round of financing is extremely negative. There is a high probability of this search for financing ending in failure. If the search for funds is fruitful, the shares in the second round of financing will be issued at a lower price than the initial round and the entrepreneur will then be massively diluted.

This is the lesser of two evils, because if the search for new investors yields no results, the entrepreneur will be forced to sell the company in very bad conditions, or to liquidate it, which is what happens most frequently.

We could consider, in order to avoid such situations, not asking investors to pay goodwill at the start during the first rounds of financing, but getting them to pay it when they exit, on the basis of the results achieved. Concretely, the shares would be issued when the company is set up, at the same price for all shareholders. Entrepreneurs will get investors to give them call options on a part of their new shareholding at a symbolic exercise price, or stock options, or warrants which will enhance the value of their shares in the future.

But there will be conditions to this enhancement – a given level of investor returns (IRR achieved in the event of sale or a new round of financing). Goodwill will then be paid by investors in the form of dilution of their rate of return, only if it is effectively delivered.

In the very likely event of something going wrong along the way, the situation can be looked at coolly and calmly by the initial shareholders who, since they have all paid the same price for their shares, will have the same interests at heart.

However, we won’t hide the fact that this will be difficult to accept for a passionate entrepreneur, who sees himself as a new Louis Vuitton or Jack Ma (Alibaba) and who hasn’t necessarily given the subject much thought.

More fundamentally, it raises the issue of the motivation and the incentive of the entrepreneur whose role in “their” company risks being symbolic, while the accretive instruments are not exercised, which will only happen in a few years. The risk is that they may consider themselves more as an employee than as an entrepreneur, and that would mean certain death for the emerging company! An entrepreneur should never behave like an employee. They should always be thinking about their project, night and day, like a soul possessed! Yes, we’re still in the realm of behavioural finance!

The whole question can be summed up as follows: “Goodwill, yes, but not too much”, so as to retain potential for enhancement of the share, capital increase after capital increase, and to avoid deadlocks or the implementation of ratchet clauses with disastrous effects for the entrepreneur. In the end, an overly optimistic business plan is not in the interests of entrepreneurs, who could find themselves sitting on a hand grenade from which they themselves have pulled the pin!

It should be noted that the creation of shares with multiple voting rights for founders makes it possible to raise large sums of money by circumventing this problem of dilution of power, whilst distinguishing it from goodwill.

Section 40.3 INVESTORS IN START-UPS

1/ INVESTORS IN EQUITY CAPITAL

The first among them is the entrepreneur, with their life savings, sometimes topped up by a bank loan that is secured by their home. They can spend the first months of the adventure with an incubator which will provide them with premises and services remunerated by a few percentage points of capital. The idea then becomes a project.

Friends and family are often among the initial investors, probably less motivated by the idea of making money, but more by loyalty! This type of investment is referred to as love money, which usually raises a few tens of thousands of euros.

Crowdfunding can be used by the entrepreneur to raise funds through specialised Internet platforms from a very large number of private investors, the most motivated of whom will invest a few hundred or a few thousand euros each. This will enable the entrepreneur to test the concept on a large scale. However, they will be lucky to raise a few hundred thousand euros in this way and struggle to raise more.

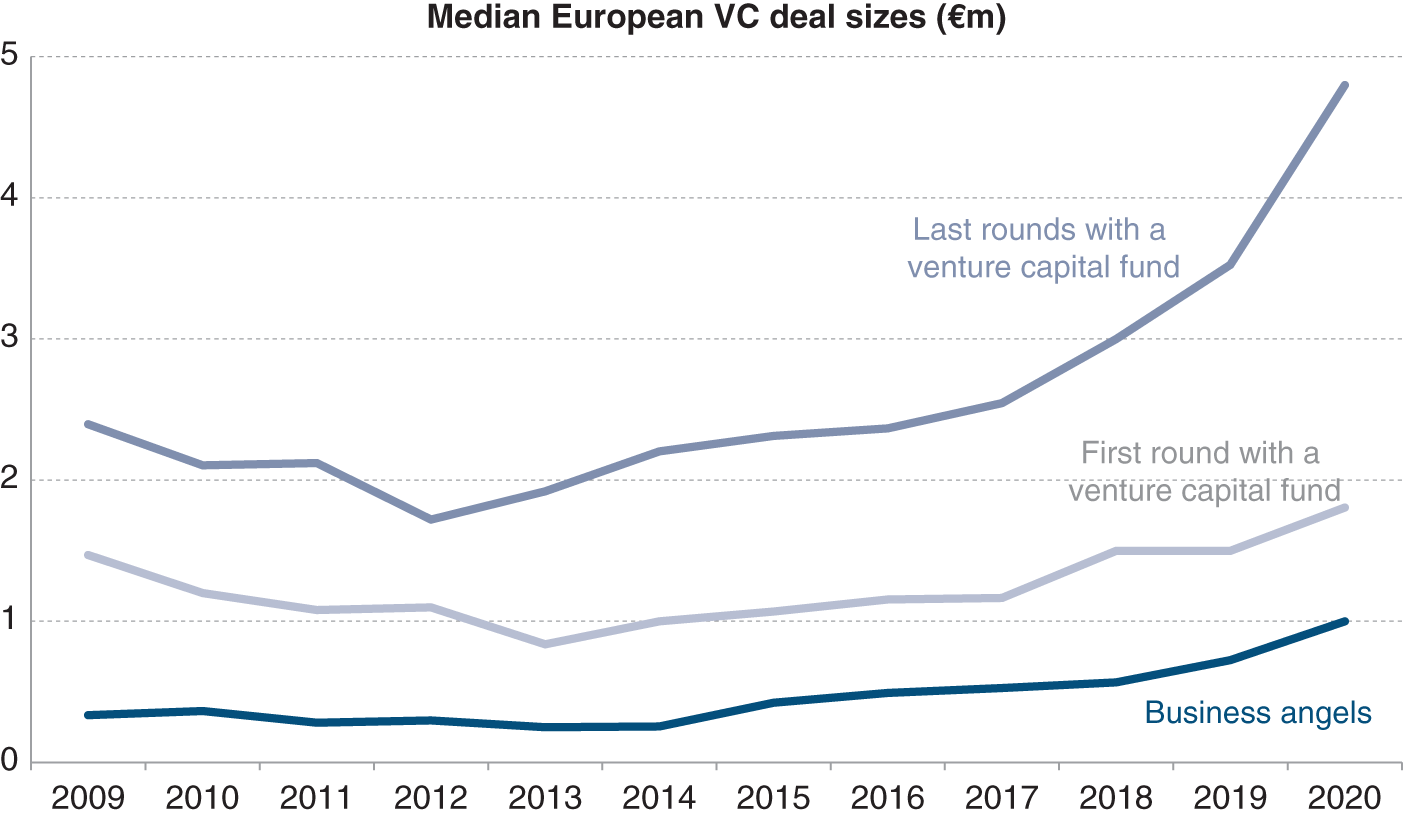

Business angels are often former company managers and shareholders. They invest a few tens or hundreds of thousands of euros per project, often called “seed money”. They also provide advice to the entrepreneur and give them access to their networks.

Venture capital funds can provide the entrepreneur with larger amounts of financing, from €0.5m to several tens of millions of euros (sometimes hundreds of millions), if the project has very high development potential.

Source: Business Employment Dynamics Report, Bureau of Labor, 2021

Some industrial groups have created internal investment funds (or joint funds for several groups in the same industry sector) with the dual aim of financing innovation and keeping a strategic watch on developments in their sector, such as Novartis, Intel, Pfizer, Orange, GE or Danone. In such cases, we refer to corporate venture.

The first round of financing from financial or industrial venture capital funds is called Series A, the second round is called Series B, the third round is called Series C, and so on.

Raising funds on the stock market by listing a company is a real possibility for companies, especially in the high-tech, Internet, biotech and medtech sectors.

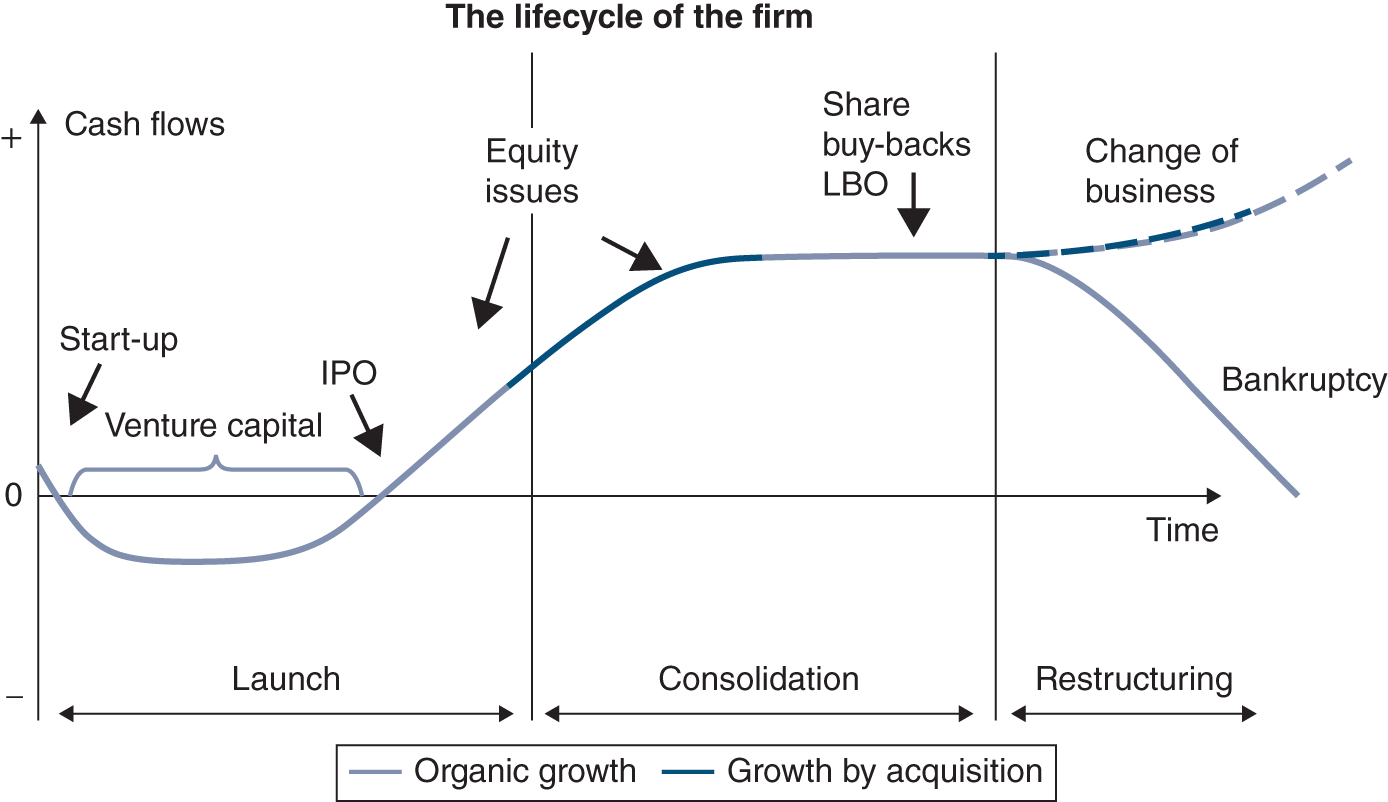

Each type of investor plays a role at the different stages of the development of the young company:

Most often investors subscribe to shares, sometimes preferred shares, given the different rights that may be granted to them, as we shall see. While waiting for a financing round that is overdue, they may be led to subscribe to a bridge financing, often taking the form of bonds redeemable in shares based on a price that will be that of the next expected financing round, minus a more or less significant discount (15 to 30%) to encourage subscription when the value of the company is unclear. Paradoxically, these bonds are often called convertible bonds, which is an abuse of language since they cannot be redeemed in cash. Alternatively, warrants are sometimes issued for the same amount, giving the right to subscribe to the nominal amount of a variable number of shares at a discount when the financing round is completed.

2/ INVESTORS IN DEBT

There are practically no investors in debt prepared to finance start-ups and, as we saw in Section 40.2, it is not in the interest of the entrepreneur to take out debt until they have demonstrated the validity of their business model.

It is only if the start-up uses or generates assets that have a value that is independent of its operations (vehicles, real estate, business) that it can make use of leasing (see Chapter 21). If it generates sales, it can finance its working capital using discounting or factoring (Chapter 21). Companies with significant R&D expenses may factor their research tax credits. An unallocated bank loan (i.e. financing the company in general rather than specific assets) will only be found if the entrepreneur provides guarantees with a value that is independent of the project. In some countries, state bodies can guarantee loans granted by commercial banks to start-ups.

3/ OTHER SOURCES OF FINANCING

These are more marginal and are often a form of supplementary financing, like subsidies, repayable advances in the event of success, honour loans granted by associations or foundations, competitions for start-ups organised by local authorities or foundations, grants by local authorities, research tax credits, etc.

Section 40.4 THE ORGANISATION OF RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN THE ENTREPRENEUR AND THE FINANCIAL INVESTORS

The relationship over time between the investors and the entrepreneur(s) is set out in the shareholders’ agreement signed at the time when the funds are handed over. See Chapter 41 for standard clauses of a shareholders’ agreement which are not used in the case of a start-up.

A shareholders’ agreement is the result of a negotiation and sets out the balance between demand for and supply of venture capital at the time that it is signed. It also reflects the power of attraction of a given start-up project or of a given entrepreneur.

1/ CLAUSES BINDING THE FOUNDER-MANAGERS

Any investor in a start-up will tell you that the main motivation behind the investment is the quality of the founding team. Accordingly, it is not surprising that investors set, as a condition for investing, the condition that the managers commit themselves fully and over the long term to this adventure. We also find clauses preventing the founders from holding other positions in other companies or from selling their shares during a certain period (lock-up); clauses that make provision for the loss of their shares and other incentives if they leave the company before a certain period (vesting), along with agreements not to compete; and clauses that give the company the intellectual property rights created by the founders.

Over and above the shareholders’ agreement, we also see mechanisms that create incentives for the founding managers, in such a way that even if they are heavily diluted by several capital increases, they remain highly motivated – stock options, call options, warrants, multiple voting rights, etc.

2/ CLAUSES THAT ARE THE CONSEQUENCE OF GOODWILL BEING PAID AT THE START

If goodwill was paid at the start, the investors will want to prevent the founders from selling the young company too soon, on the basis of a valuation that enables them to recover only a part of their investment while the founders could make a comfortable capital gain (see Exercise 2 for an illustration). In order to avoid this situation, provision can be made that the income from the sale of the company goes first to the investors, in the amount of their investment (sometimes capitalised using a minimum rate of return), and is then shared out between investors and founders whose interests are then aligned.

This provision, known as the preferential liquidity clause, is also used in the event of a resale or liquidation several years after the first round, to protect the most recent investors who have normally paid the highest price. A sale of the company at a price lower than the last round of financing might be convenient for the previous shareholders, including the founders, who have lower cost prices, but would put the most recent investors at a loss. To avoid this situation, and because they agree to pay a higher price thereby reducing the dilution of the current shareholders, the most recent investors will often ask for a preferential liquidity clause. However, in order to allow founders and investors from previous rounds of financing to be able to retrieve their funds even in the event of a low resale price, a partial equal distribution is most often included at the beginning along the following lines:

- 20% of the price is usually shared pro rata among all shareholders, including the founders (“carve out”).

- The remainder of the sale’s proceeds are allocated first to investors from the most recent fundraising round, until repayment of their investment, with returns possibly capitalised, and after deducting any amounts received in the first allocation.

- Finally, the remainder (if any) is distributed to all the other shareholders (including the founders) in due proportion to their holdings.

This clause only comes into play if the sale (or liquidation) price is insufficient to allow the investors of the last round to recover their investment (sometimes with capitalisation), via a normal distribution of the proceeds of the sale in proportion to their holdings.

The preferential liquidity clause is undoubtedly a protection for investors against valuation inflation, at least until the next round of financing. It is also undoubtedly a factor in the valuation inflation of successful start-ups, as investors are less concerned about the level of valuation since they are protected from overvaluation. Current shareholders and founders accept it because it allows for higher, more flattering and less dilutive valuations, and because they hope that the company’s development will lead to a further increase in its value and that this clause will therefore not come into play.

The preferential liquidity clause tends to eliminate the ratchet clause, whose implementation dilutes management too massively. This clause allows investors in the first rounds to receive free shares in subsequent rounds of financing carried out at prices lower than their entry price (an illustration of this is provided in Exercise 4).

3/ CLAUSES RELATED TO THE LIQUIDITY OF THE INVESTMENT

There are different clauses that seek to ensure that investors are able to sell their stakes in such a way as to reap the benefits of their investment. This is, moreover, one of the stated aims of an investment fund, which itself is often required, at the latest when it is wound up, to distribute the income from its investments.

Accordingly, investors can get the founders to agree to the sale of all of their shares in the company after a certain period, if the majority shareholders have not provided them with sufficient liquidity for their investment. A sale of the majority of the shares will enable them to get a better price than if they had only offered a (generally) minority stake for sale (see Section 31.6). Having said that, implementing this clause is very difficult because if the entrepreneur doesn’t want to sell despite having pledged to, they will not be very convincing when trying to get a buyer to make an offer.

Very often, the investors want to be able to sell all or part of their shares before the founders sell theirs, in the case of an IPO or a planned sale by the founders. If they are not given this priority, they may ask for the option to sell the same percentage of their stakes as the founders in the event of a sale (tag-along clause) or if there is a change in control over the company. A drag-along clause is nearly always introduced to provide a group of majority shareholders representing a given percentage of the capital with the option of forcing the other shareholders to sell their shares on the same terms as those offered to them by a buyer. Such a buyer may condition its offer on obtaining all of the capital and in this case, the majority shareholders will not want to have to cope with being blackmailed by a minority shareholder.

4/ CLAUSES RELATED TO CONTROL BY INVESTORS OVER COMPANY DECISIONS

Demonstrating that they are keen to be more closely associated with the running of the young company and the risks that they are prepared to take, investors often require a level of information that is accurate, wide, frequent and adapted to the situation and the activity of the company.

Additionally, provision can be made that certain important decisions (such as modification of the articles of association (by-laws), hiring of key staff, modification of the company’s strategy, investments, acquisitions or disposals, etc.) can only be taken by a qualified majority, giving investors a de facto veto right.

Section 40.5 THE FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT OF A START-UP

There are two principles that underlie the financial management of a start-up: keep a very close watch on the cash position and plan the next round of fundraising very well.

Cash on the assets side of the balance sheet, when there is no monthly cash income, measures the number of months of survival of the company before it is obliged to carry out another round of fundraising. This is called the burn rate. How much time does the company have to reach its next step or to shift from plan A, which has failed, to plan B, which has to be invented and implemented?

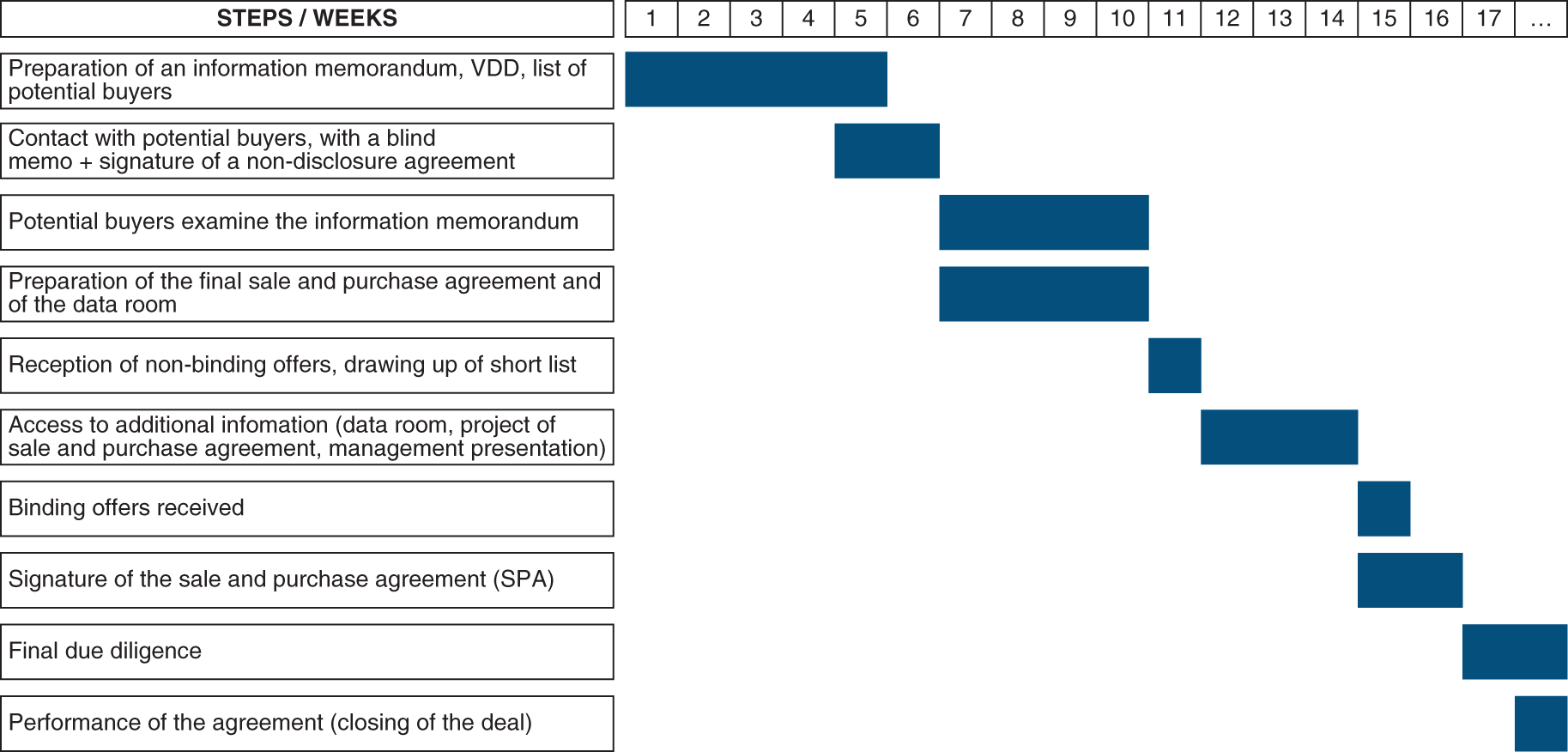

Unless the existing shareholders have the financial resources necessary to cover the financing of the next round and agree to do so, the manager of the start-up would be well advised to launch the process of looking for new investors six to nine months at the latest before their cash runs out. Since a round of financing most often covers requirements for the next 12 to 24 months, it comes around quickly. The search for new investors and the conviction needed are very time-consuming, especially for a manager who doesn’t have a financial director to help them.

Launching a new round of financing early is often too early: the company has not yet shown that it has reached a new step in its development since the last round of fundraising. Waiting until later means taking the risk of running out of cash during the final phase of negotiations with investors, at the risk of having to admit defeat.

Section 40.6 THE PARTICULARITIES OF VALUING YOUNG COMPANIES

It is obviously very difficult to value a company that has not yet proved the relevance of its business model, which has a high probability of disappearing in the short term, and for which projections are so uncertain that sometimes one might ask whether they’re worth the paper they’re printed on.

One might thus think that the real option method seen in Chapter 30 is particularly well suited to valuing the young company because the way it works in stages is very similar to the successive stages of development that the young company must go through. In practice, this is not the case at all and it is practically never used in this field. Drawing up a business plan that makes sense and that is also optimistic is complicated, but asking an entrepreneur to draft different versions, including one which leads to bankruptcy, is counter-productive. Do we really want to demoralise and discourage the entrepreneur at a time when they need to be boosted in order to meet the challenges they are facing? Of course not!

Valuation by discounting free cash flows (see Chapter 31) is not very widespread, even though the basic raw material for this method, the business plan, is often available. In order to avoid using this method, investors raise the pretext of the extreme volatility of business plans for start-ups, given that there is very little chance of new companies sticking to them and the fact that they reflect the best of possible outcomes, rather than the most likely. Conceptually, though, there is nothing that prevents this method from being used by looking at the probabilities of several projections.

As for the multiples method (see Chapter 31), given that its use is conditional on the existence of comparable listed companies, it is de facto unusable for valuing very young companies, which are all different from each other and very rarely listed on the stock exchange. Additionally, the fact that most of them have negative earnings would render the operation impossible.

Our reader may be surprised by the very crude nature of the valuation of start-ups, which is more a matter of convention than of calculation. At least for its first rounds of financing, the value of a start-up usually results from a multiple of the amount of funds sought to reach the next level in 12 to 24 months, and/or what amounts to the same thing, the percentage of dilution that the founders agree to.

Practice has shown that a pre-money valuation (i.e. before the capital increase) of 1 to 1.5 times the amount sought is the sign of an unfavourable period for entrepreneurs corresponding to a relative scarcity of capital ready to invest at this stage of company development. In order to finance the next 12 to 24 months, entrepreneurs must be satisfied with 50% to 60% of the company’s capital. They will therefore very quickly lose control, as it is unlikely that there will be just one fund raising. Beyond four times, and the opposite happens and we’re probably in a bubble period. The entrepreneur then succeeds in selling only 20% at most of the share capital during this round of financing.

In normal times we are between 2 and 3, and the founders are diluted from 25% to 33% of the capital.

| Funds raised (m€) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-money value (m€) | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | |

| 1 | 2 | ||||||

| 33% | |||||||

| 1.5 | 3 | 1.5 | |||||

| 25% | 40% | ||||||

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 1.3 | ||||

| 20% | 33% | 43% | |||||

| 2.5 | 5 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.3 | |||

| 17% | 29% | 38% | 44% | ||||

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.2 | |||

| 25% | 33% | 40% | 45% | ||||

| 4 | 4 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | ||

| 20% | 27% | 33% | 38% | 43% | |||

| 5 | 5 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2 | 1.7 | ||

| 17% | 23% | 29% | 33% | 38% | |||

| 7.5 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 2.5 | |||

| 17% | 21% | 25% | 29% | ||||

| 10 | 5 | 4 | 3.3 | ||||

| 17% | 20% | 23% | |||||

The table above shows in each box the multiplier coefficient of the fundraising round, and the level of dilution suffered by the founders (which also corresponds to the ownership percentage of investors). We have not filled in the boxes that seem to us to be outliers, where the founders lose control from the first round of investment, or where the valuation bubble stretches to the moon!

We remind our horrified reader that the risk to the investor at this very early stage is not overvaluation, but bankruptcy.

For start-ups that have survived and progressed to an advanced stage of development, venture capital professionals have developed a method that is rather pragmatic and efficient, if a bit simplistic, which they use for valuing young companies, known as the venture capital method. As you will see, it is a hybrid of the multiples and discounted free cash flow methods.

We start by estimating the probable value of the company’s equity in four to seven years, when it will have reached a level of maturity to allow it either to be listed or to be sold to a third party, most frequently an industrial player. This timeframe corresponds to the exit of the venture capitalist and to the fact that the company is no longer a start-up (hopefully) but a developing company. This future value is calculated by applying the P/E ratio today, observed for companies in this stage of development, to net earnings forecast in the business plan at this period (for more on the P/E ratio, see Chapter 22); for example, 15 times net earnings of €8m, i.e. €120m.

Secondly, and in order to determine the present value, this future value of equity is discounted to a value today, using a high discount rate since the company is at an early stage of its development.3 The rates most frequently observed are as follows:

| Phase | Discount rate | Equivalent to multiply the investment by | Over … years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Start-up (Seed) | 60% | 11.2 | 7 |

| First round | 50% | 7.6 | 5 |

| Second round | 40% | 3.8 | 4 |

| Third round | 30% | 2.2 | 3 |

| Before IPO | 20% | 1.4 | 2 |

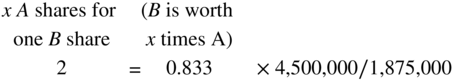

So, for a pure start-up, with a business plan period of seven years, the value today of the equity is €120m / (1 + 60%)7 = €4.5m. This result is post-money as it assumes that the company has found the financing necessary for developing its activities. If today it needs €1.5m, the value of its equity is €4.5 – €1.5 = €3m. The investor who contributes these funds gets 33% (1.5 / 4.5) of the company’s equity. If the company’s capital is made up of a million shares, the investor will have to be issued with 500,000 new shares at a unit price of €3.

The reader will not be surprised at how high these rates are and will have difficulty reconciling them with those provided by the CAPM in Chapter 19 or with the average IRR obtained by venture capital funds (between 15% and 30%), and rightly so, as they are of another order.

If they appear to be high, it is because they integrate the risk of the start-up going bankrupt. They are applied to a level of earnings that does not correspond to the average of different scenarios, but to a business plan that reflects, by construction, the success of the company. However, over a five-year period, at least 40% of companies will have disappeared and out of those that are left, a large number will not have lived up to expectations. Accordingly, the high discount rate takes into consideration the risk that the projections will turn out to have been too optimistic, which is most often the case.

The rate of return required by the investor also takes into account the illiquidity of the investment (see Section 19.4) and also remunerates the non-financial contributions by the investor (operational or managerial advice, network access, etc.).

Our rather simplistic model assumes that a single round of fundraising was necessary before reaching a stage where the company could be sold or listed. Let’s assume that there is a second round of fundraising of €5m in year three. At the time of this fundraising, the post-money valuation of the company made by the second investor, who would require a rate of return of 40%, would be: €120m / (1 + 40%) = €31.2m, which results in a percentage for this second investor of 5 / 31.2 = 16%.

The terminal value remains €120m since it assumes, if it is to be achieved, a second round of fundraising. Our first investor will be diluted by this second capital increase. Accordingly, they thus need to hold a larger part of the capital after their contribution of funds, to set off the dilutive effect of the second capital increase and to obtain their rate of return of 60%. This stake is calculated as follows: 33% / (1 – 16%) = 39.3%. Instead of 500,000 new shares issued in the first round of financing, which would give 33% of the share capital to our first investor, 647,000 new shares4 should be issued. Since the latter is still bringing €1.5m to the table, this means that the shares are issued at a unit price of €1.5m / 0.647m = €2.32, and no longer €3, when there is no subsequent dilution.

If, in seven years’ time, the value of the company’s equity capital is indeed €120m, our first investor, who took a 39.3% stake in the capital when the company was started up, which was then diluted three years later to 33%, can sell their stake for €40m. For an investment of €1.5m made seven years earlier, they have, in fact, obtained their rate of return of 60% per year. As for the second investor who invested €5m in the third year and who got 16% of the capital, the sale of these shares in year seven for 16% × €120m = €19.2m gives them their required rate of return of 40% per year.

The venture capital method is also used backwards. A purchase price of shares is offered to you and you want to find the implicit rate of return of this investment if the business plan is met and given your estimation of the final value of the company. You then compare it with the minimum rate of return that you estimate is justified, given the risk of the investment, in order to take your investment decision. Here we find the IRR of Chapter 17.

Section 40.7 EXAMPLE INSPIRED BY A REAL CASE: EXAMPLE.COM

The simplified joint stock company Example SAS was set up eight years ago by two friends with the aim of developing a new-generation social network around the website Example.com, which offers a very powerful yet simple tool based on complex algorithms that had required years of development.

The first round of financing brought together friends and business angels, who contributed €0.6m. Dilution of capital was only 17% thanks to a high level of goodwill, since the managers only contributed €0.1m. This situation is explained by the following: in addition to the quality of the entrepreneurs, algorithms had been pre-developed, giving a clear idea of the development potential, a worldwide market was being targeted and ambitions were high, and finally the entrepreneurs had declined to be paid a salary during the first two years.

On the basis of the launch of the alpha version of the site Example.com one year later, which demonstrated that the algorithms were correct, Example SAS carried out a second capital increase of €1m, which was followed by the original investors, at a share price that was 50% higher. Because Example SAS was keen to speed up its development, which would involve increasing its losses and its working capital, it made the choice to carry out this capital increase relatively quickly, even though its cash position would have enabled it to defer it for a year. Sometimes it is better to stand fast than to run and to avoid financial stress that could have operational consequences. For example, it is easier to recruit a good IT developer when your cash can cover 24 months of cash burn rather than three!

A third capital increase was carried out one year later, which raised €1.9m. Five new investors (mainly business angels) participated in this capital increase alongside some of the original investors. The launch of the beta version of the site and the development of the community, which was growing at 30% per month, played a determining role in the success of this operation.

Example preferred to wait until the last moment to carry out its fourth capital increase, which at €6m was a large one, nearly double the equity raised previously. When it was finalised, Example SAS only had three months of cash left! The iPad version had just been launched with success and the community had reached 460,000 members, which works out at a monthly growth rate of 18%. The share price could thus be maximised: +40% compared with the capital increase carried out 18 months previously, resulting in dilution of only 30%, but growth in book equity of 1250%. This should be the last capital increase before profits start rolling in.

The funds raised enabled Example to test two revenue models, premium and advertising, which had been partially successful but which failed to lead to equilibrium. Four years later, a final capital increase of €2m was subscribed, at a price per share that was 60% lower than that of the previous capital increase. The challenge for Example will be to break into two new markets that are seen as buoyant markets – the university and the media markets. This is a shift that will require a resizing of the company and a change in profile for a large portion of its workforce. Initial results are promising.

Today, there are 3 million Example users worldwide, with 50% in the USA, 25% in France, and the rest of the world accounting for the last quarter. The two founders, who had brought 1% of the funds raised, hold 35% of the shares and the investors, who brought 99% of the funds, hold 65% of the shares.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 In this chapter we use the terms founder, creator or manager of a start-up as synonyms for entrepreneurs.

- 2 Synonym in this chapter for young company.

- 3 For more on discounting, see Chapter 16.

- 4 647,000 / (1,000,000 + 647,000) = 39.3%.

Chapter 41. SHAREHOLDERS

What a cast of characters!

Section 41.1 SHAREHOLDER STRUCTURE

Our objective in this section is to demonstrate the importance of a company’s shareholder structure. While the study of finance generally includes a clear description of why it is important to value a company and its equity, analysis of who owns its shares and how shareholders are organised is often neglected. Yet in practice this is where investment bankers often look first.

There are several reasons for looking closely at the shareholder base of a company. Firstly, the shareholders theoretically determine the company’s strategy, but we must understand who really has power in the company, the shareholders or the managers. You will undoubtedly recognise the mark of “agency theory”. This theory provides a theoretical explanation of shareholder–manager problems.

Secondly, we must know the objectives of the shareholders when they are also the managers. Wealth? Power? Fame? In some cases, the shareholder is also a customer or supplier of the company. In an agricultural cooperative, for example, the shareholders are upstream in the production process. The cooperative company becomes a tool serving the needs of the producers, rather than a profit centre in its own right. This is probably why many agricultural cooperatives are not very profitable.

Lastly, disagreement between shareholders can paralyse a company, particularly a family-owned company.

As a last word, do not forget, as seen in Chapter 26, that in the financial world everything has a price, or better, everything can create or destroy value.

1/ DEFINITION OF SHAREHOLDER STRUCTURE

The shareholder structure (or shareholder base) is the percentage ownership and the percentage of voting rights held by different shareholders. When a company issues shares with multiple voting rights or non-voting preference shares or represents a cascade of holding companies, these two concepts are separate and distinct. A shareholder with 33% of the shares with double voting rights will have more control over a company where the remaining shares are widely held than will a shareholder with 45% of the shares with single voting rights if two other shareholders hold 25% and 30%. A shareholder who holds 20% of a company’s shares directly and 40% of the shares of a company that holds the other 80% will have rights to 52% of the company’s earnings but will be in the minority for decision-taking. In the case of companies that issue equity-linked instruments (convertible bonds, warrants, stock options) attention must be paid to the number of shares currently outstanding versus the fully diluted number of potential shares.

Studying the shareholder structure depends very much on the company being listed or not. In unlisted companies, the equilibrium between the different shareholders depends heavily on shareholders’ agreements which are often in place, but rarely public and difficult to gain access to for the external analyst, impacting the relevancy of their analysis. For a listed company, shareholder attendance at previous general meetings should be analysed. If attendance has been low, a shareholder with a large minority stake could have de facto control, like Bolloré at Vivendi, in which it only has 29% of the voting rights.

Lastly, we should mention nominee (warehousing) agreements even though they are rarely used these days. Under a nominee agreement, the “real” shareholders sell their shares to a “nominee” and make a commitment to repurchase them at a specific price, usually in an effort to remain anonymous. A shareholder may enter into a nominee agreement for one of several reasons: transaction confidentiality, group restructuring or deconsolidation, etc. Conceptually, the nominee extends credit to the shareholder and bears counterparty and market risk. If the issuer runs into trouble during the life of the nominee agreement, the original shareholder will be loath to buy back the shares at a price that no longer reflects reality. As a result, nominee agreements are difficult to enforce. Moreover, they can be invalidated if they create an inequality among shareholders. We do not recommend the use of nominee agreements. The modern form for listed companies is the equity swap.1

2/ LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Theoretically, in all jurisdictions, the ultimate decision-making power lies with the shareholders of a company. They exercise it through the assembly of a shareholders’ Annual General Meeting (AGM). Nevertheless, the types of decisions can differ from one country to another. Generally, shareholders decide on:

- appointment of board members;

- appointment of auditors;

- approval of annual accounts;

- distribution of dividends;

- changes in articles of association (i.e. the constitution of a company);

- mergers;

- capital increases and share buy-backs;

- dissolution (i.e. the end of the company).

In most countries – depending on the type of decision – there are two types of shareholder vote: ordinary and extraordinary.

At an Ordinary General Meeting (OGM) of shareholders, shareholders vote on matters requiring a simple majority of voting shares. These include decisions regarding the ordinary course of the company’s business, such as approving the financial statements, payment of dividends and appointment and removal of members of the board of directors.

At an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) of shareholders, shareholders vote on matters that require a change in the company’s articles of association: share issues, mergers, asset contributions, demergers, share buy-backs, etc. These decisions require a qualified majority. Depending on the country and on the legal form of the company, this qualified majority is generally two-thirds or three-quarters of outstanding voting rights.

The main levels of control of a company in various countries are as follows:

| Supermajority | Type of decision | |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 1/2 | Changes in the objective of the company Merger, demerger Dissolution Changes in preferred share characteristics |

| China | 2/3 | Increase or reduction of the registered capital Merger, split-up Dissolution of the company Change of the company form |

| France | 2/3 | Changes in the articles of association Merger, demerger Capital increase and decrease Dissolution |

| Germany | 3/4 | Changes in the articles of association Reduction and increase of capital Major structural decisions Merger or transformation of the company |

| India | 3/4 | Merger |

| Italy | — | Defined in the articles of association |

| Netherlands | 2/3 | Restrictions in pre-emption rights Capital reduction |

| Russia | 3/4 | Changes in the articles of association Reorganisation of the company Liquidation Reduction and increase in capital Purchase of own shares Approval of a deal representing more than 50% of the company’s assets |

| Spain | — | Defined in the articles of association |

| Switzerland | 2/3 | Changes in purpose Issue of shares with increased voting powers Limitations of pre-emption rights Change of location Dissolution |

| UK | 3/4 | Altering the articles of association Disapplying members’ statutory pre-emption rights on issues of further shares for cash Capital decrease Approving the giving of financial assistance/purchase of own shares by a private company or, off market, by a public company Procuring the winding up of a company by the court Voluntarily winding up a company |

| USA | — | Defined on a state level and frequently in the articles of association |

Shareholders holding less than the blocking minority (if this concept exists in the country) of a company that has another large shareholder with a majority, have a limited number of options open to them. They cannot change the company objectives or the way it is managed. At best, they can force compliance with disclosure rules, or call for an audit or an EGM. Their power is most often limited to being that of a naysayer. In other words, a small shareholder can be a thorn in management’s side, but no more. Nevertheless, the voice of the minority shareholder has become a lot louder and a number of them have formed associations to defend their interests. Shareholder activism has become a defence tool where the law had failed to provide one.

It should be noted that in some countries (Sweden, Norway, Portugal) minority shareholders can force the payment of a minimum dividend. In some countries, all shareholders, irrespective of the number of shares they hold, have the right to ask questions in writing at the General Meeting. The company must answer them publicly at the latest on the day of the meeting.

A shareholder who holds a blocking minority (one-quarter or one-third of the shares plus one share depending on the country and the legal form of the company) can veto any decision taken in an extraordinary shareholders’ meeting that would change the company’s articles of association, company objects or called-up share capital.

A blocking minority is in a particularly strong position when the company is in trouble, because it is then that the need for operational and financial restructuring is the most pressing. The power of blocking minority shareholders can also be decisive in periods of rapid growth, when the company needs additional capital.

The notion of a blocking minority is closely linked to exerting control over changes in the company’s articles of association. Consequently, the more specific and inflexible the articles of association are, the more power the holder of a blocking minority wields.

3/ THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF SHAREHOLDERS

(a) The family-owned company

By “family-owned” we mean that the shareholders have been made up of members of the same family for several generations and, often through a holding company, exert significant influence over management. This is still the dominant model in Europe. The following table shows the shareholder base of the 50 largest companies by market capitalisation in several countries (2021):

| Shareholding | Germany | Switzerland | USA | France | Italy | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widely spread | 50% | 54% | 84% | 43% | 20% | 82% |

| Family (and non-listed) | 20% | 32% | 14% | 31% | 38% | 6% |

| State and local authorities | 10% | 8% | 0% | 14% | 22% | 4% |

| Financial institution | 2% | 4% | 0% | 6% | 12% | 6% |

| Other listed firms | 18% | 2% | 2% | 6% | 8% | 2% |

Source: Company data, FactSet.

However, this type of shareholder structure is on the decline for several reasons:

- some new or capital-intensive industries, such as energy/utilities and banks require so much capital that a family-owned structure is not viable over the long term. Indeed, family ownership is more suited to consumer goods, retailing, services, processing, etc.;

- financial markets have matured and financial savings are now properly rewarded, so that, with rare exceptions, diversification is a better investment strategy than concentration on a specific risk (see Section 18.6);

- increasingly, family-owned companies are being managed on the basis of financial criteria, prompting the family group either to exit the capital or to dilute the family’s interests in a larger pool of investors that it no longer controls. This trend requires a nuanced view as, in recent years, certain young companies whose founders remain very important shareholders (Contentsquare, Doordash, Iliad, and so on) have taken up a prominent role within the economy.

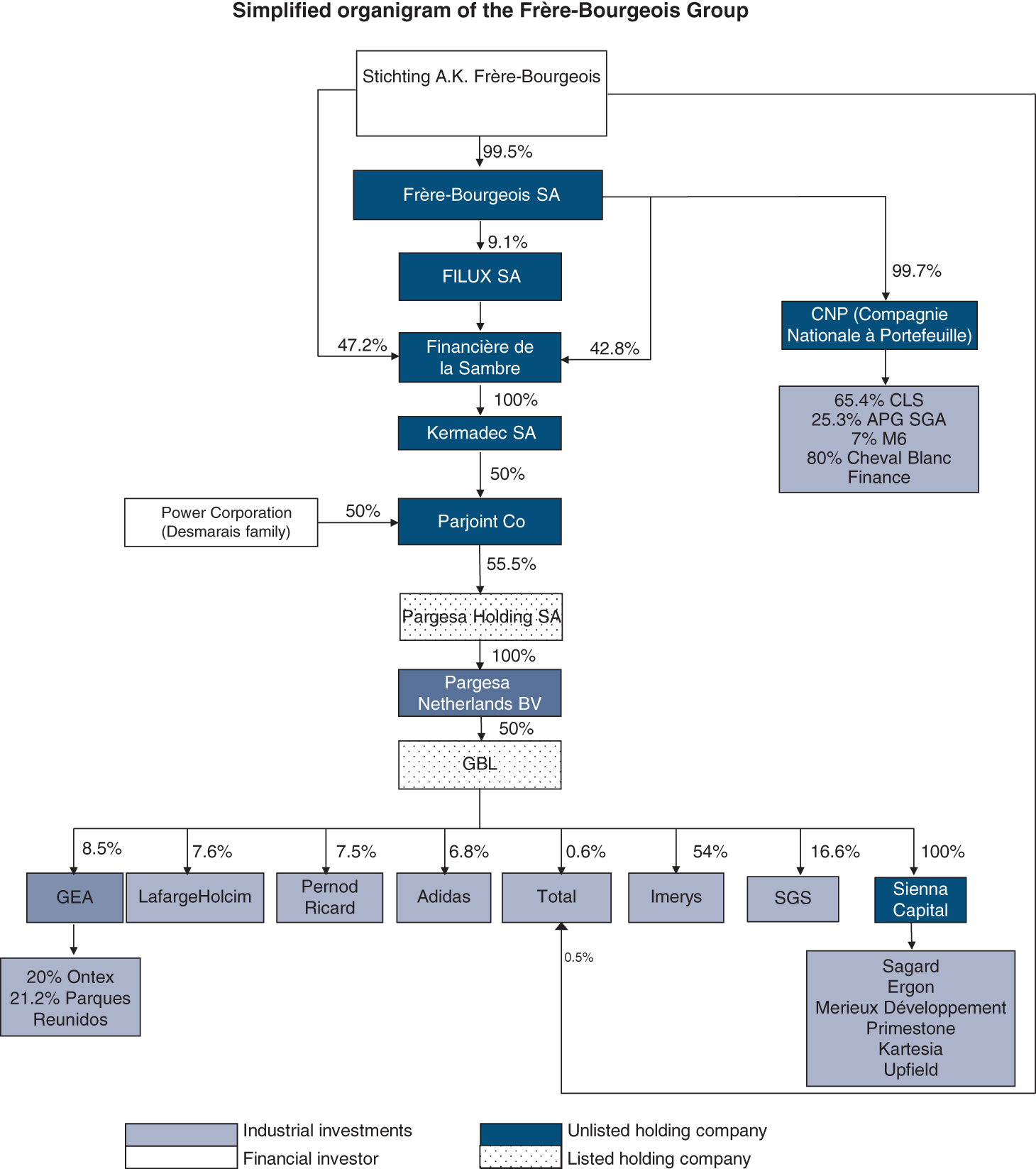

Family shareholding sometimes reappears in the form of family offices, emanating from large industrial families (Desmarais in Canada, Quandt in Germany, Frère in Belgium, etc.) that invest in financial fundamentals, but with a much longer-term perspective than traditional funds.

Some research has demonstrated that family-owned companies register on average better performance than non-family-owned companies. Having most of your wealth in one single company or group is a strong incentive to properly monitor its managers or to act responsibly as its manager.

(b) Business angels

See Chapter 40.

(c) Private equity funds

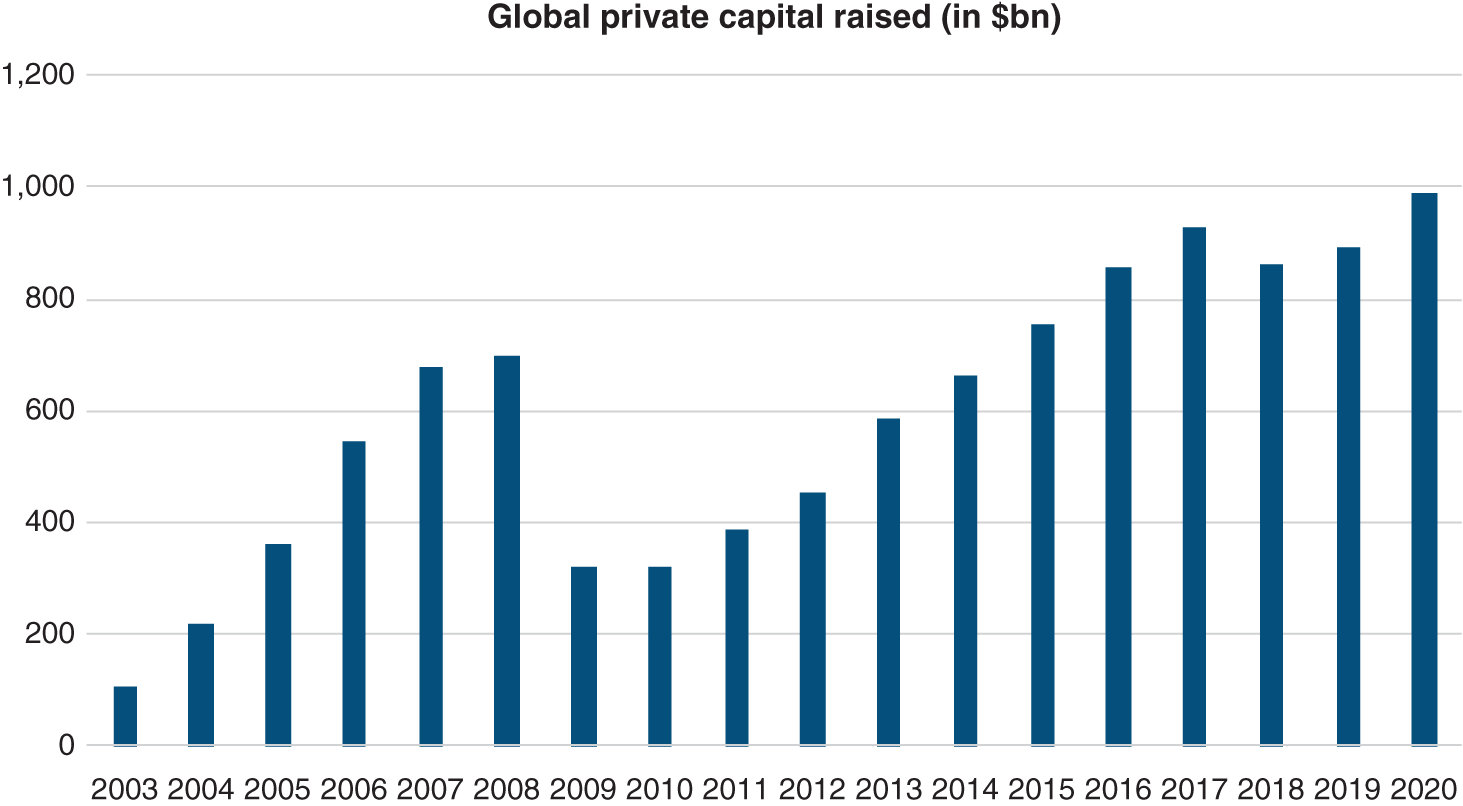

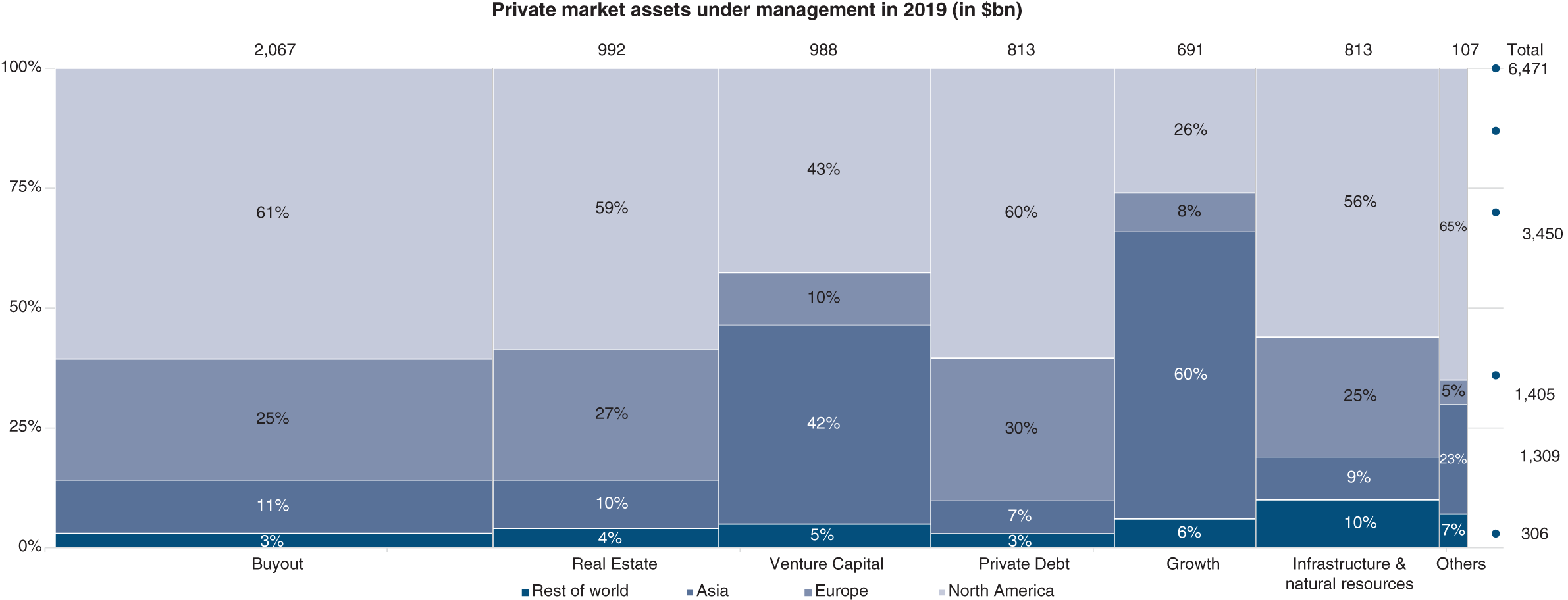

Private equity funds, financed by insurance companies, pension funds or wealthy investors, play a major role. In most cases these funds specialise in a certain type of investment: venture capital, development capital, LBOs (see Chapter 47) or turnaround capital, which correspond to a company’s different stages of maturity.

Venture capital funds focus on bringing seed capital, i.e. equity, to start-ups to finance their early developments.

Development capital funds become shareholders of high-growth companies that require substantial funds.

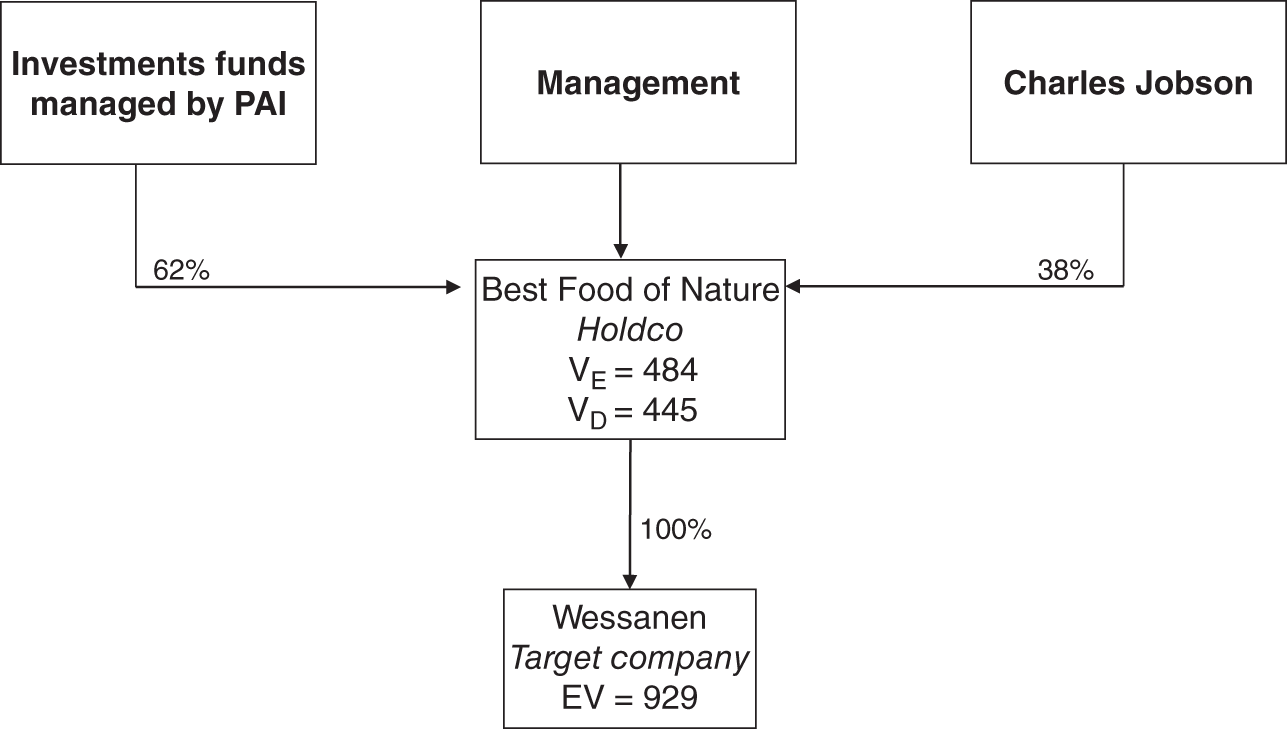

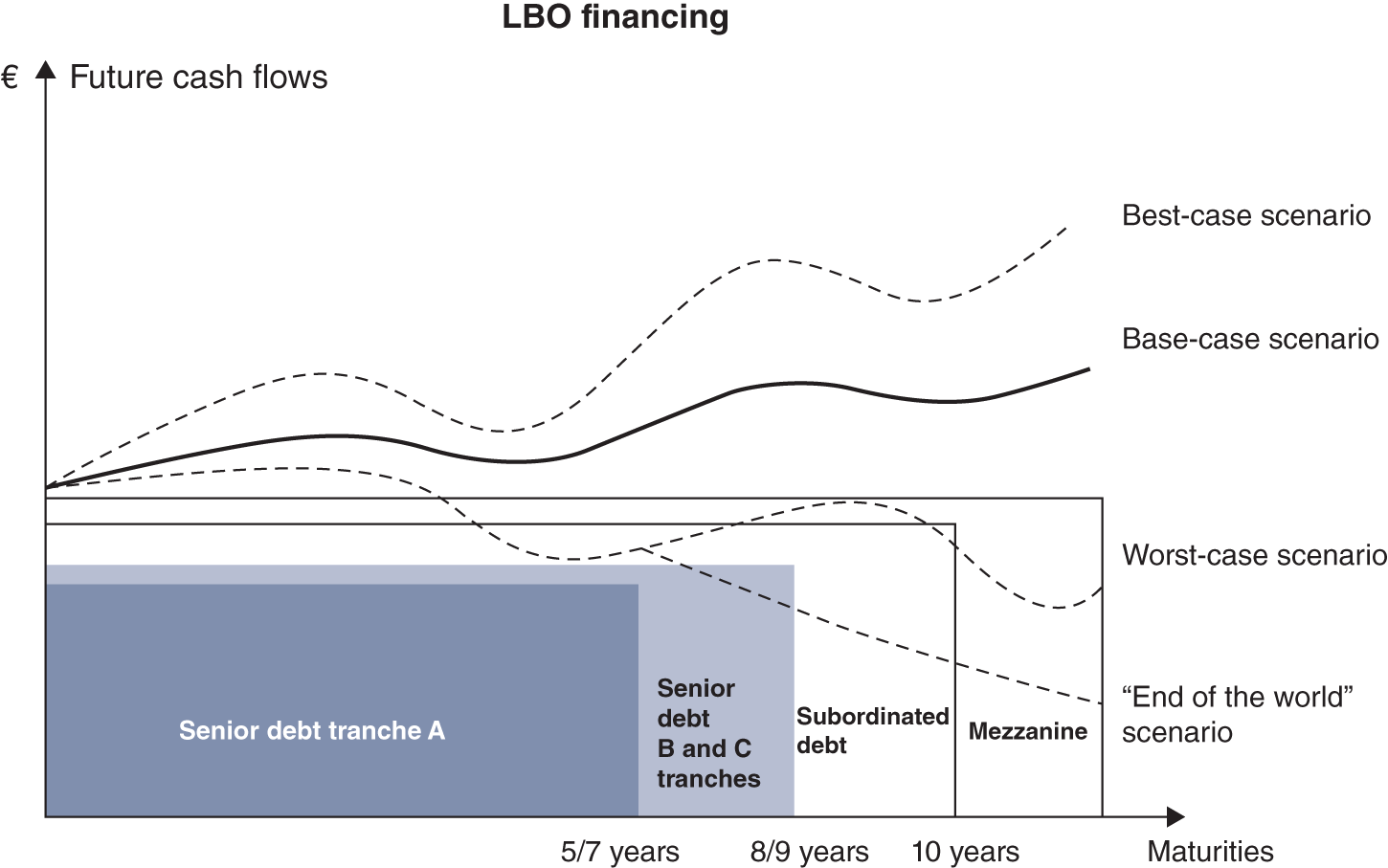

LBO funds invest in companies put up for sale by a group looking to refocus on its core business or by a family-held group faced with succession problems, or help a company whose shares are depressed (in the opinion of the management) to delist itself in a public-to-private (P-to-P) transaction. LBO funds are keen to get full control over a company (but control can be exercised by 2 or 3 funds) in order to reap all of the rewards and also to make it possible to restructure the company as they think best, without having to worry about the interests of minority shareholders. Therefore, they usually prefer the target companies not to be listed (or to be delisted if the target was public), but the fund itself can be listed.

Turnaround funds work with distressed companies, helping them to turn themselves around.

Activist funds have made a speciality of putting public pressure on poorly performing or badly structured groups, proposing corrective measures to improve their value. In 2020, for example, Amber was proposing a complete overhaul of Lagardère’s board of directors, a change of strategy and the abandonment of the limited partnership status that protects the founder’s heir, who has not demonstrated the same qualities. This has been implemented in 2021.

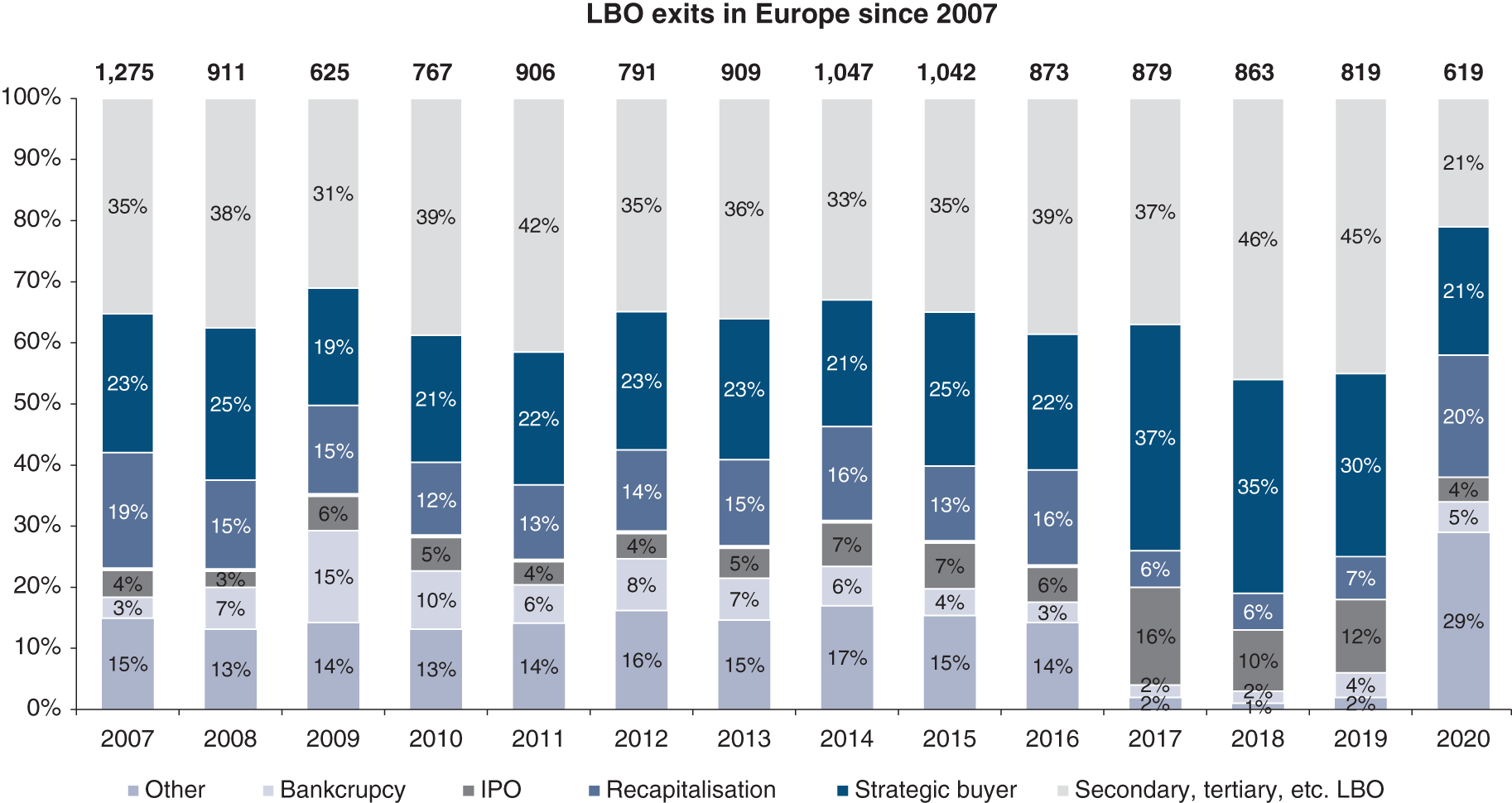

Managed by teams of investment professionals whose compensation is largely linked to performance, these funds have a limited lifespan (no more than 10 years). Before the fund is closed, the companies that the fund has acquired are resold, floated on the stock exchange or the fund’s investments are taken over by another fund.

Some private equity funds take a minority stake in listed companies, a PIPE (private investment in public equity), helping the management to revitalise the company so as to make a capital gain. For example, in 2019, Searchlight Capital took a 26% stake in Latécoère and changed the CEO in 2020. In 2020–2021, the creation of SPACs by private equity funds allowed them to invest in companies on a minority basis when they went public using this technique.

Private equity funds play an important role in the economy and are a real alternative to a listing on the stock exchange. They solve agency problems by putting in place strict reporting from the management, which is incentivised through management packages and the pressure of debt (LBO funds).

They also bring a cash culture to optimise working capital management and limit capital expenditure to reasonably value-creating investments. Private equity funds are ready to bring additional equity to finance acquisitions with an industrial logic. They also bring to management a capacity to listen, to advise and to exchange, which is far greater than that provided by most institutional investors. They are professional shareholders who have only one aim – to create value – and they do not hesitate to align the management of companies they invest in with that objective.

(d) Institutional investors

Institutional investors are banks, asset managers, insurance companies, pension funds and unit trusts that manage money on behalf of private individuals. Most of the time they individually own minor stakes (less than 10%), but they play a much bigger role as they define the stock market price of companies in which they collectively represent the major part of their floating capital.

Because of new regulations on corporate governance (see Chapter 43), they vote at AGMs more frequently, especially to defeat resolutions they do not like, notably regarding excessive compensation.

(e) Financial holding companies

Large European financial holding companies such as Deutsche Bank, Paribas, Mediobanca, Société Générale de Belgique, etc. played a major role in creating and financing large groups. In a sense, they played the role of the (then-deficient) capital markets. Their gradual disappearance or mutation has led to the breakup of core shareholder groups and cross-shareholdings. Today, in emerging countries (Korea, India, Colombia), large industrial and financial conglomerates play their role (Samsung, Tata, Votorantim, etc.).

(f) Employee-shareholders

Many companies have invited their employees to become shareholders. In most of these cases, employees hold a small proportion of the shares, although in a few cases the majority of the shares. This shareholder group, loyal and non-volatile, lends a degree of stability to the capital and, in general, strengthens the position of the majority shareholder, if any, and of the management.

The main schemes to incentivise employees are:

- Direct ownership. Employees and management can invest directly in the shares of the company. In LBOs, private equity sponsors bring the management into the shareholding structure to minimise agency costs.

- Employee stock ownership programmes (ESOPs). ESOPs consist in granting shares to employees as a form of compensation. Alternatively, the shares are acquired by shareholders but the firm will offer free shares so as to encourage employees to invest in the shares of the company. The shares will be held by a trust (or employee savings plan) for the employees. Such programmes can include lock-up clauses to maintain the incentive aspect and limit flowback (see Section 25.2). In this way, the shares allocated to each employee will vest (i.e. become available) gradually over time.

- Stock options. Stock options are a right to subscribe to new shares or shares held by the company as treasury stocks at a certain point in time.

For service companies and fast-growing companies, it is key to incentivise employees and management with shares or stock options, as the key assets of such companies are their people. For other companies, offering stock to employees can be part of a broader effort to improve employee relations (all types of companies) and promote the company’s image internally. The success of such a policy largely depends on the overall corporate mood. In large companies, employees can hold up to 10%. Lehman, the US investment bank, was one of the listed companies with the largest employee shareholdings (c. 25%) when it went into meltdown in 2008.

Regardless of the type of company and its motivation for making employees shareholders, you should keep in mind that the special relationship between the company and the employee-shareholder cannot last forever. Prudent investment principles dictate that the employee should not invest too heavily in the shares of the company that pays their salaries, because in so doing they, in fact, compound the “everyday life” risks they are running.2

Basically, the company should be particularly fast-growing and safe before the employee agrees to a long-term participation in the fruits of its expansion. Most often, this condition is not met. Moreover, just because employees hold stock options does not mean they will be loyal or long-term shareholders. The LBO models we will study in Chapter 47 become dangerous when they make a majority of the employees shareholders. In a crisis, the employees may be keener to protect their jobs than to vote for a painful restructuring. When limited to a small number of employees, however, LBOs create a stable, internal group of shareholders.

(g) Governments

In Europe and the USA, governments’ role as the major shareholders of listed groups is fading, even if they are still majority shareholders of large industry players (Deutsche Bahn, EDF, Enel) or playing a key role in some groups like Deutsche Telekom, Airbus or Eni. State ownership had a period of revival thanks to the economic crisis, as some groups were taken over to avoid collapse (General Motors, RBS) or funds were injected through equity issues to reinforce financial institutions (Citi, ING, etc.).

At the same time, sovereign wealth funds, mostly created by emerging countries and financed thanks to reserves from staples, are gaining importance as long-term shareholders. They are normally very financially minded, but their opacity, their size (often between €50bn and €500bn) and their strong connections with mostly undemocratic states are worrying to some. As of end 2020, they had c. $9,070bn under management, and slowly growing. The most well-known include The Government Pension Fund of Norway, Norges ($1,290bn), China Investment Company (CIC, $1,045bn), SAFE Investment Company and Hong Kong Monetary Authority ($978bn) from China, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA, $745bn), GIC and Temasek in Singapore ($710bn), Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA, $562bn), etc. They are majority shareholders of a number of firms (Singapore Airlines, P&O, etc.) and minority shareholders in some listed firms such as the London Stock Exchange, Glencore, KKR, Carlyle, Foncia, etc.

(h) Crossholdings

Crossholdings peaked before the 1990s when capitalism was often capital-less. Today, the very few examples (Renault owns 43% of Nissan, which owns 15% of Renault, Spotify owns 9% of Tencent Music, which owns 7.5% of Spotify) are there to promote industrial synergies, or even to prepare for a closer future relationship, and not for financial or power reasons.

4/ SHAREHOLDERS’ AGREEMENT

Minority shareholders can protect their interests by crafting a shareholders’ agreement with other shareholders.

A shareholders’ agreement is a legal document signed by several shareholders to define their future relationships. It complements the company’s articles of association. Most of the time, the shareholders’ agreement is confidential except for listed companies in countries which require its publication in order for it to be valid.

They mainly contain two sets of clauses:

- clauses that organise corporate governance: breakdown of directors’ seats, the nomination of the chairperson, of the CEO, of the auditors; how major decisions are taken, including capex; financing, acquisitions, share issues, dividend policy; how to vote during annual general meetings; what kind of information is disclosed to shareholders, etc.;

- clauses that organise the sale or purchase of shares in the future: lock-up, right of first refusal if one shareholder wants to exit, drag-along (to force the disposal of 100% of the shares if the majority shareholders or several shareholders holding a majority stake between them wish to exit) or tag-along (to allow minority shareholders to benefit from the same transaction conditions if the majority shareholder is selling), caps and floors, etc.

- For shareholders’ agreement on start-ups, please see Section 40.4.

Section 41.2 HOW TO STRENGTHEN CONTROL OVER A COMPANY

Defensive measures for maintaining control of a company always carry a cost. From a purely financial point of view, this is perfectly normal: there are no free lunches!

With this in mind, let us now take a look at the various takeover defences. We will see that they vary greatly depending on the country, on the existence or absence of a regulatory framework and on the powers granted to companies and their executives. Certain countries, such as the UK and, to a lesser extent, France and Italy, regulate anti-takeover measures strictly, while others, such as the Netherlands and the USA, allow companies much more leeway.

Broadly speaking, countries where financial markets play a significant role in evaluating management performance, because companies are more widely held, have more stringent regulations. This is the case in the UK and France.

Conversely, countries where capital is concentrated in relatively few hands have more flexible regulation. This goes hand in hand with the articles of association of the companies, which ensure existing management a high level of protection. In Germany, half of the seats on the board of directors are reserved for employees, and board members can be replaced only by a 75% majority vote.

Paradoxically, when the market’s power to inflict punishment on companies is unchecked, companies and their executives may feel such insecurity that they agree to protect themselves via the articles of association. Sometimes this contractual protection is to the detriment of the company’s welfare and of free market principles. This practice is common in the US.

Defensive measures fall into four categories:

- Separate management control from financial control:

- different classes of shares: shares with multiple voting rights and non-voting shares;

- holding companies;

- limited partnerships.

- Control shareholder changes:

- right of approval;

- pre-emption rights.

- Strengthen the position of loyal shareholders:

- reserved capital increases;

- share buy-backs and cancellations;

- mergers and other tie-ups;

- employee shareholdings;

- warrants.

- Exploit legal and regulatory protection:

- regulations;

- voting caps;

- strategic assets;

- change-of-control provisions.

In order to defend itself, a company must know who its shareholders are. This is relatively easy for unlisted companies for which shares must be nominative, but a lot more complicated for listed companies, where most of the shares are bearer shares (the identity of the shareholder is unknown to the company). In this way, some companies are able to make provision for the notification obligation, set out in the articles of association, when a minimum threshold (0.5%, for example) of the share capital has been breached, which is in addition to statutory obligations starting at 3 or 5% in most countries (see Section 45.3).

1/ SEPARATING MANAGEMENT CONTROL FROM FINANCIAL CONTROL

(a) Different classes of shares: shares with multiple voting rights and non-voting shares

As an exception to the general rule, under which the number of votes attributed to each share must be directly proportional to the percentage of the capital it represents (principle of one share, one vote), companies in some countries have the right to issue multiple-voting shares or non-voting shares.

In the Netherlands, the USA, Luxembourg, and the Scandinavian countries, dual classes of shares are not infrequent. The company issues two (or more) types of shares (generally named A shares and B shares) with the same financial rights but with different voting rights.

French corporate law provides for the possibility of double-voting shares but, contrary to dual-class shares, all shareholders can benefit from the double-voting rights if they hold the shares for a certain time.

Multiple-voting shares can be particularly powerful; for example, the founders of Alphabet (ex. Google) have 53.1% of voting rights of Alphabet while they hold only 11.6% of the shares. Ford, Snap, Lyft, Facebook, and Roche, have also put in place this type of capital structure. These dual-class shares can appear as unfair and contrary to the principle that the person who provides the capital gets the power in a company. Some countries (Italy, Spain, Belgium and Germany) have outlawed dual-class shares.

(b) Holding companies

Holding companies can be useful but their intensive use leads to complex, multi-tiered shareholding structures. As you might imagine, they present both advantages and disadvantages.

Suppose an investor holds 51% of a holding company, which in turn holds 51% of a second holding company, which in turn holds 51% of an industrial company. Although they hold only 13% of the capital of this industrial company, the investor uses a cascade of holding companies to maintain control of the industrial company.

A holding company allows a shareholder to maintain control over a company, because a structure with a holding disperses the minority shareholders. Even if the industrial company were floated on the stock exchange, the minority shareholders in the different holding companies would not be able to sell their stakes.

Maximum marginal personal income tax is generally higher than income taxes on dividends from a subsidiary. Therefore, a holding company structure allows the controlling shareholder to draw off dividends with a minimum tax bite and use them to buy more shares in the industrial company.

Technically, a holding company can “trap” minority shareholders; in practice, this situation often leads to an ongoing conflict between shareholders. For this reason, holding companies are usually based on a group of core shareholders intimately involved in the management of the company.

A two-tiered holding company structure often exists, where:

- a holding company controls the operating company;

- a top holding company holds the controlling holding company. The shareholders of the top holding company are the core group. This top holding company’s main purpose is to buy back the shares of minority shareholders seeking to sell some of their shares.

Often, a holding company is formed to represent the family shareholders prior to an IPO.

(c) Limited share partnerships (LSPs)

A limited share partnership is a company where the share capital is divided into shares, but with two types of partners:

- several limited partners with the status of shareholders, whose liability is limited to the amount of their investment in the company. A limited share partnership is akin to a public limited company in this respect;

- one or more general partners, who are jointly liable, to an unlimited extent, for the debts of the company. Senior executives of the company are usually general partners, with limited partners being barred from the executive suite.

The company’s articles of association determine how present and future executives are to be chosen. These top managers have the most extensive powers to act on behalf of the company in all circumstances. They can be fired only under the terms specified in the articles of association. In some countries, the general partners can limit their financial liability by setting up a (limited liability) family holding company. In addition, the LSP structure allows a change in management control of the operating company to take place within the holding company. For example, a father can hand over the reins to his daughter, while the holding company continues to perform its management functions.