About the Authors

Pascal Quiry holds the BNP Paribas Chair in Finance at HEC Paris and he is a founder of an investment fund which specialises in investing in start-ups and unlisted SMEs. He is a former managing director in the M&A division of BNP Paribas where he was in charge of deals execution.

Yann Le Fur is head of the Corporate Finance Group of Natixis Americas after working as an investment banker for a number of years, notably with Schroders, Citi and Mediobanca and as an M&A director for Alstom.

Pierre Vernimmen, who died in 1996, was both an M&A dealmaker (he advised Louis Vuitton on its merger with Moët Hennessy to create LVMH, the world luxury goods leader) and a finance teacher at HEC Paris. His book Finance d’Entreprise was, and still is, the top-selling financial textbook in French-speaking countries and is the forebear of Corporate Finance: Theory and Practice.

Preface

This book aims to cover the full scope of corporate finance as it is practised today worldwide.

A way of thinking about finance

We are very pleased with the success of the first five editions of the book. It has encouraged us to retain the approach in order to explain corporate finance to students and professionals. There are four key features that distinguish this book from the many other corporate finance textbooks available on the market today:

- Our strong belief that financial analysis is part of corporate finance. Pierre Vernimmen, who was mentor and partner to some of us in the practice of corporate finance, understood very early on that a good financial manager must first be able to analyse a company’s economic, financial and strategic situation, and then value it, while at the same time mastering the conceptual underpinnings of all financial decisions.

- Corporate Finance is neither a theoretical textbook nor a practical workbook. It is a book in which theory and practice are constantly set off against each other, in the same way as in our daily practice as investors at Monestier capital and Natixis, as board members of several listed and unlisted companies, and as teachers notably at HEC Paris business school.

- Emphasis is placed on concepts intended to give you an understanding of situations, rather than on techniques, which tend to shift and change over time. We confess to believing that the former will still be valid in 20 years’ time, whereas the latter will, for the most part, be long forgotten!

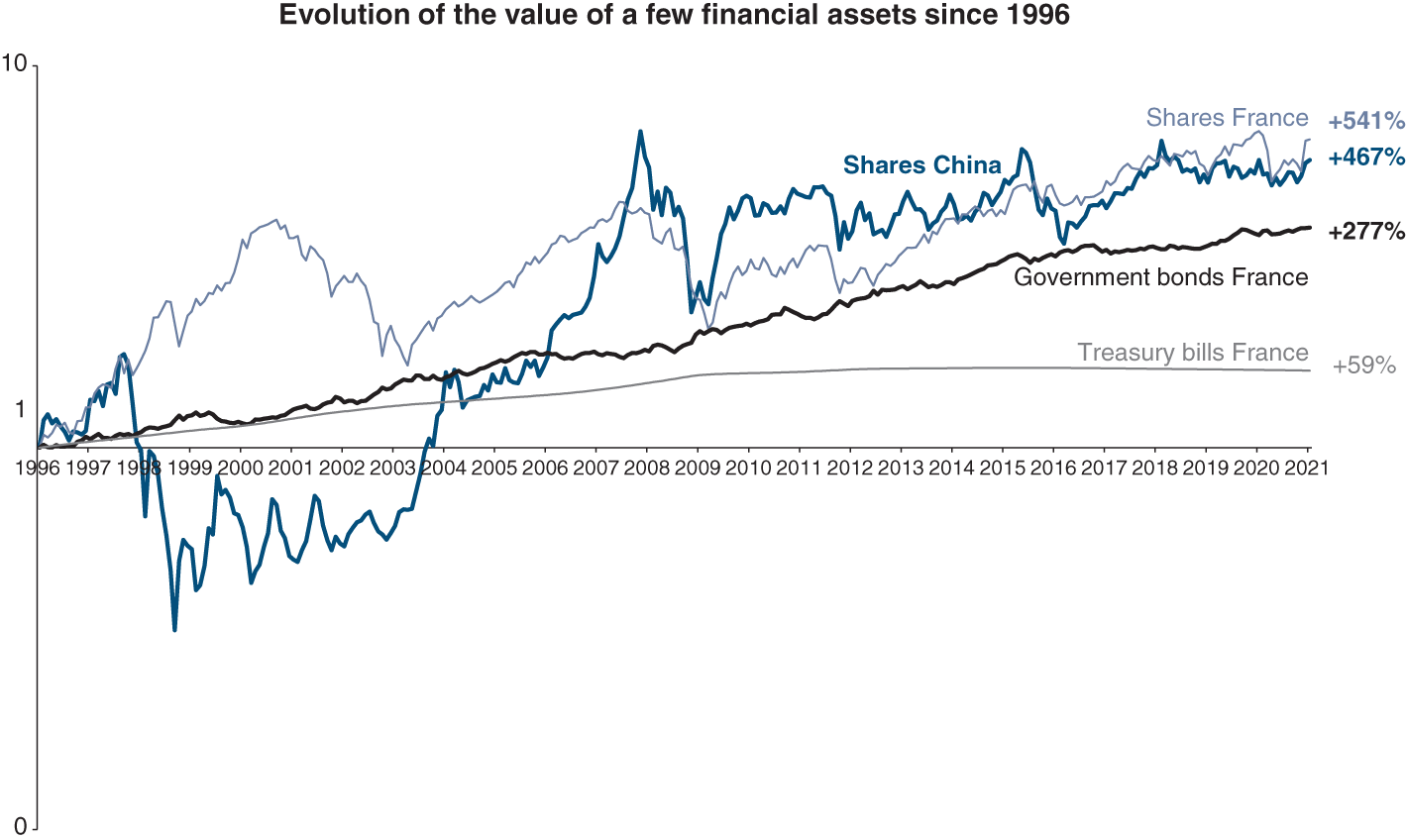

- Financial concepts are international, but they are much easier to grasp when they are set in a familiar context. We have tried to give examples and statistics from all around the world to illustrate the concepts.

The five sections

This book starts with an introductory chapter reiterating the idea that corporate financiers are the bridge between the economy and the realm of finance. Increasingly, they must play the role of marketing managers and negotiators. Their products are financial securities that represent rights to the firm’s cash flows. Their customers are bankers and investors. A good financial manager listens to customers and sells them good products at high prices. A good financial manager always thinks in terms of value rather than costs or earnings.

Section I goes over the basics of financial analysis, i.e. understanding the company based on a detailed analysis of its financial statements. We are amazed at the extent to which large numbers of investors neglected this approach during the latest stock market euphoria. When share prices everywhere are rising, why stick to a rigorous approach? For one thing, to avoid being caught in the crash that inevitably follows.

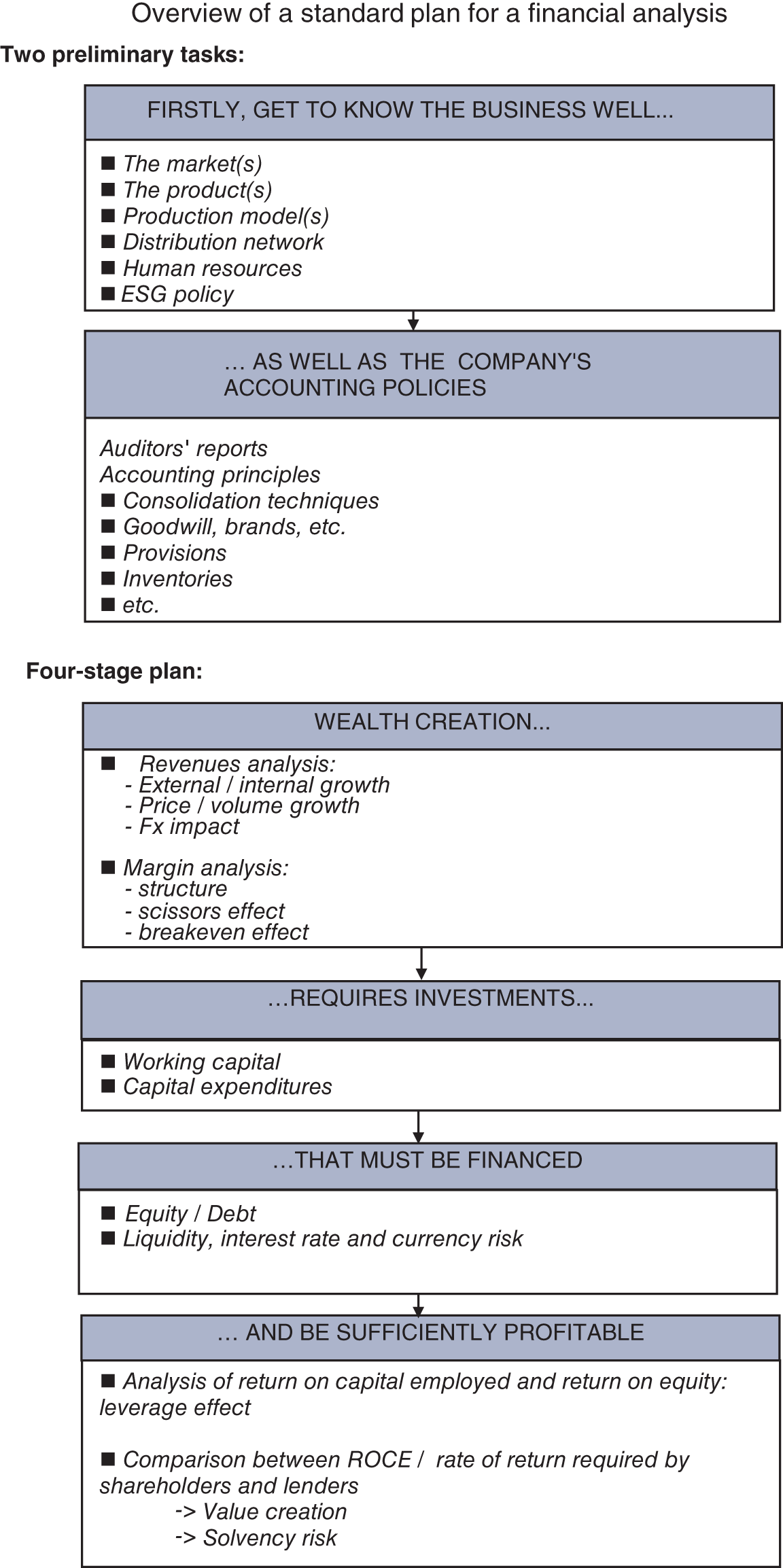

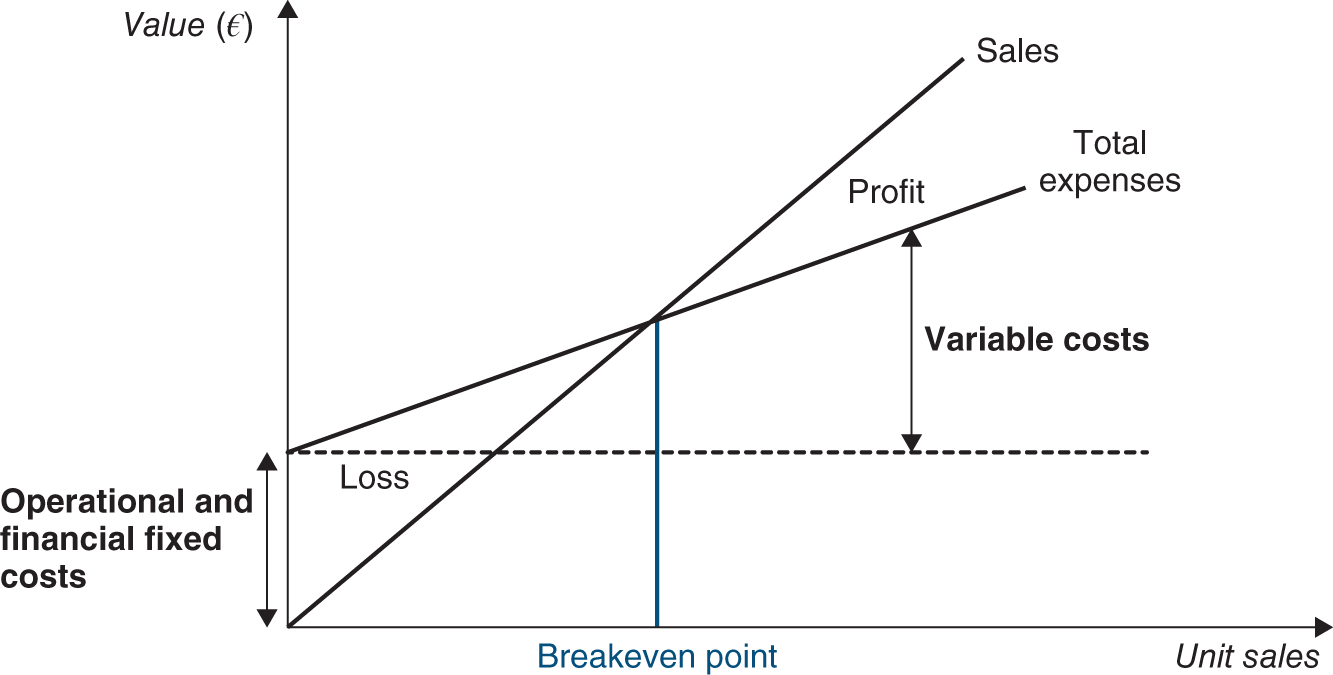

The return to reason has also returned financial analysis to its rightful place as a cornerstone of economic decision-making. To perform financial analysis, you must first understand the firm’s basic financial mechanics (Chapters 2). Next you must master the basic techniques of accounting, including accounting principles, consolidation techniques and certain complexities (Chapters 6), based on international (IFRS) standards now mandatory in over 80 countries, including the EU (for listed companies), Australia, South Africa and accepted by the SEC for US listing. In order to make things easier for the newcomer to finance, we have structured the presentation of financial analysis itself around its guiding principle: in the long run, a company can survive only if it is solvent and creates value for its shareholders. To do so, it must generate wealth (Chapters 9 and 10), invest (Chapter 11), finance its investments (Chapter 12) and generate a sufficient return (Chapter 13). The illustrative financial analysis of the Italian appliance manufacturer Indesit will guide you throughout this section of the book.

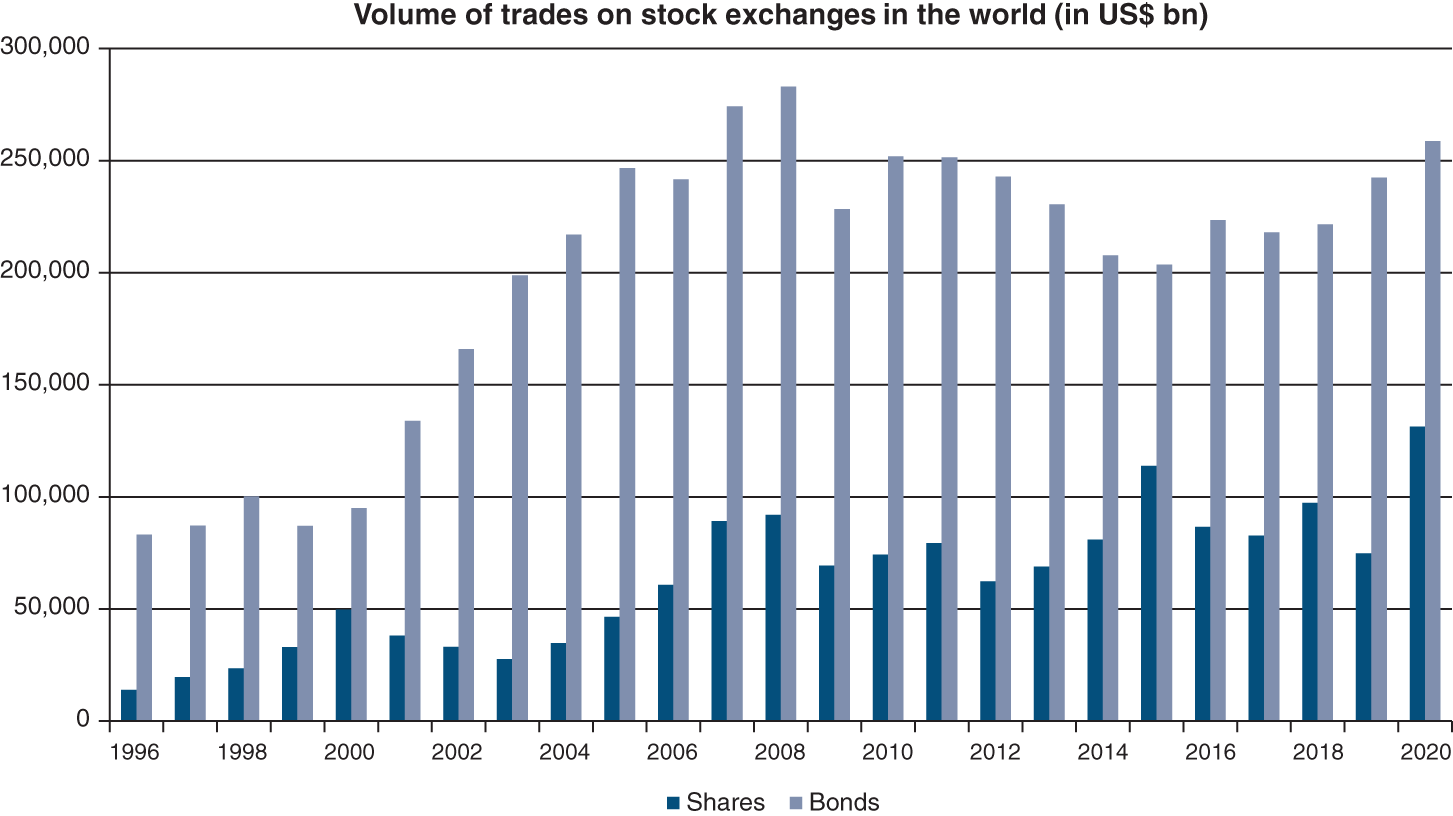

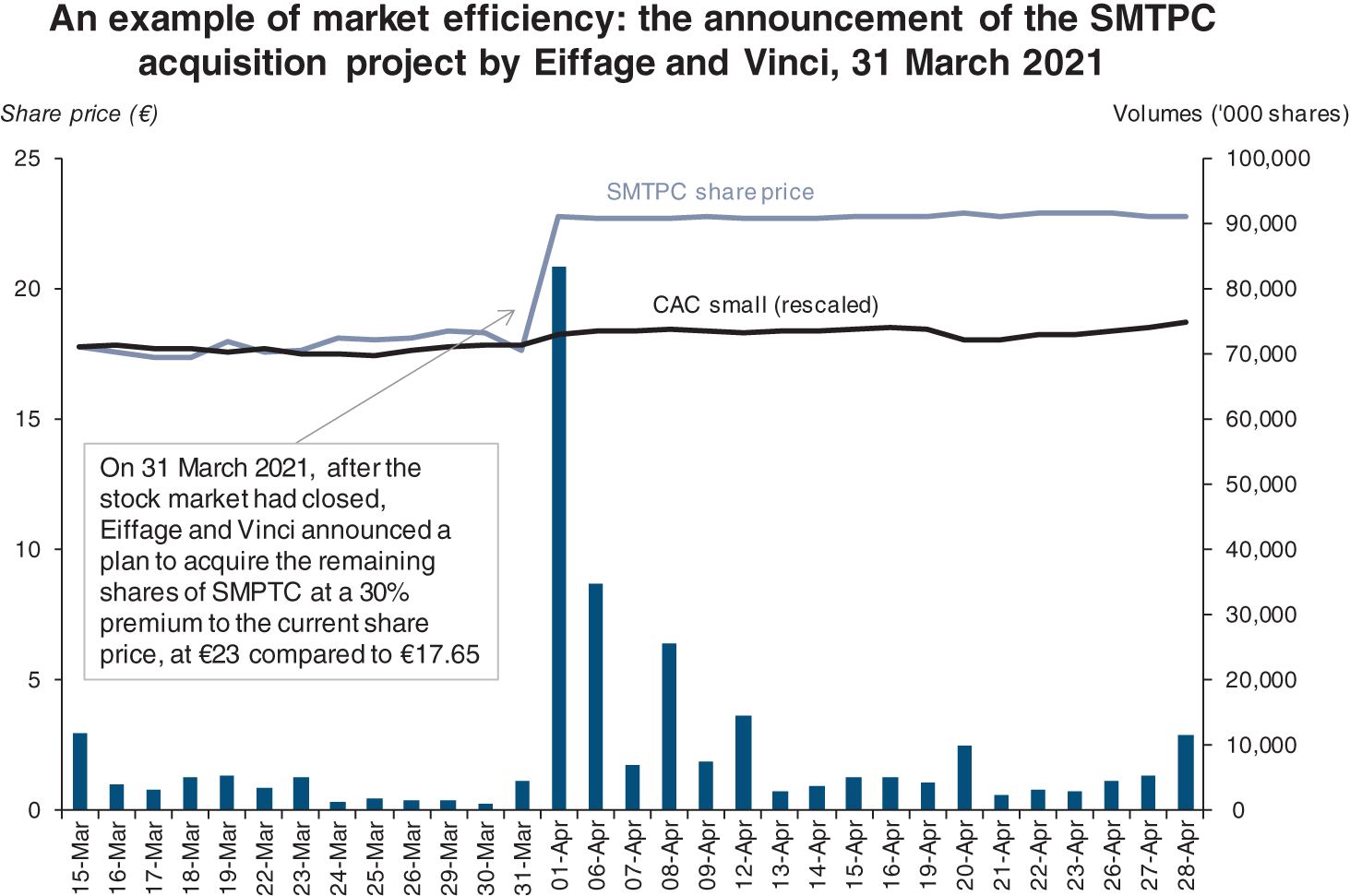

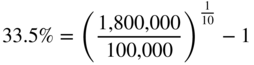

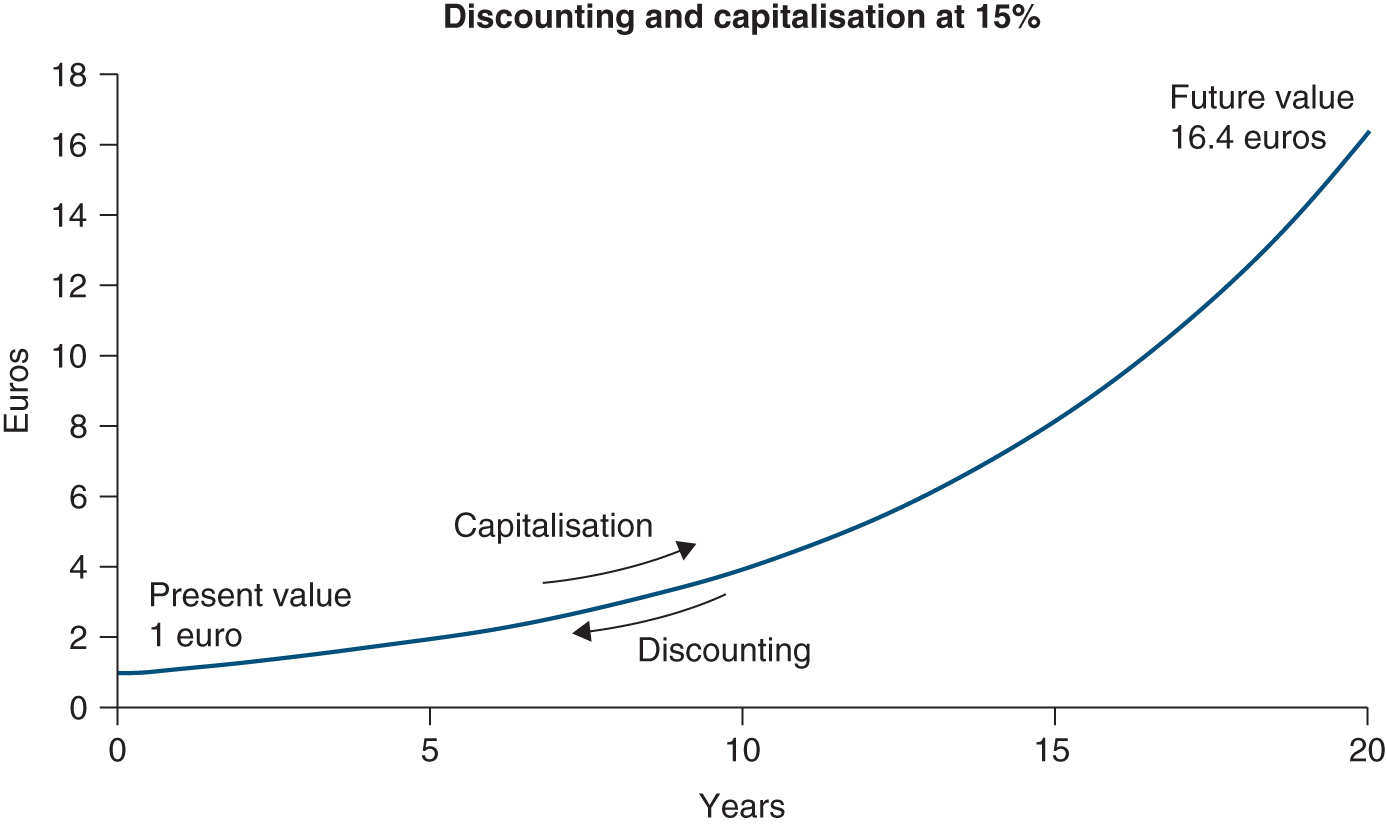

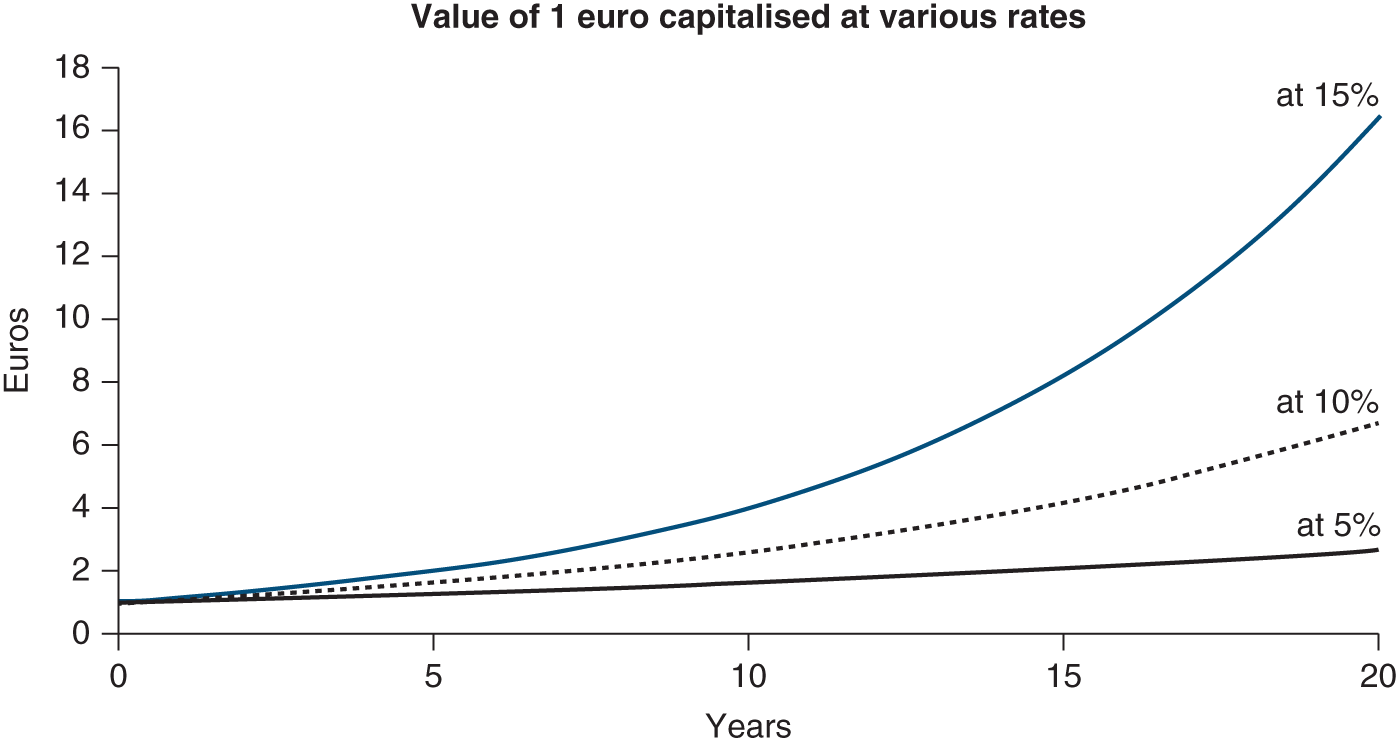

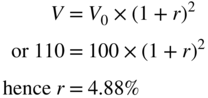

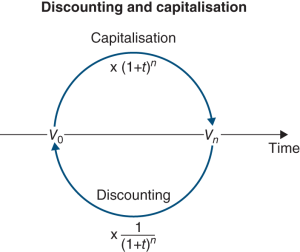

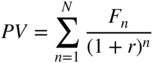

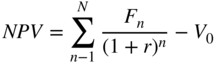

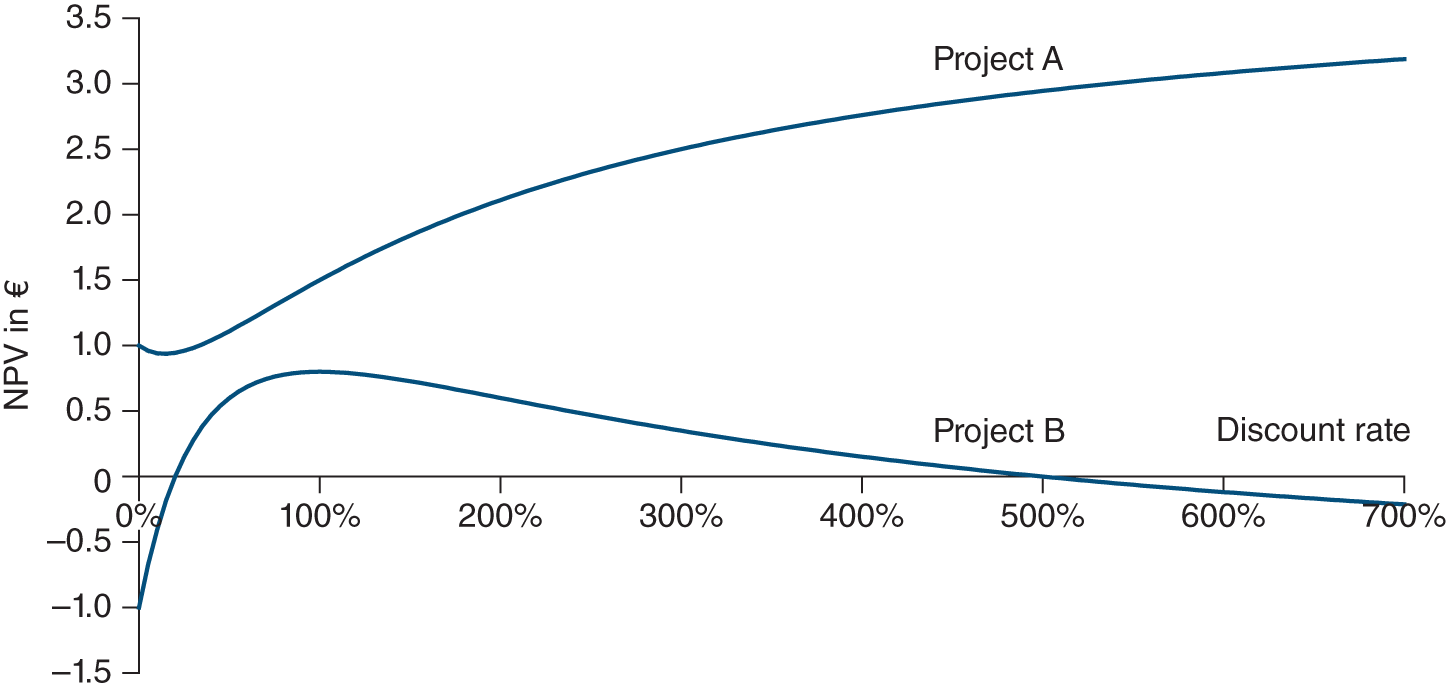

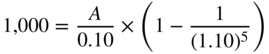

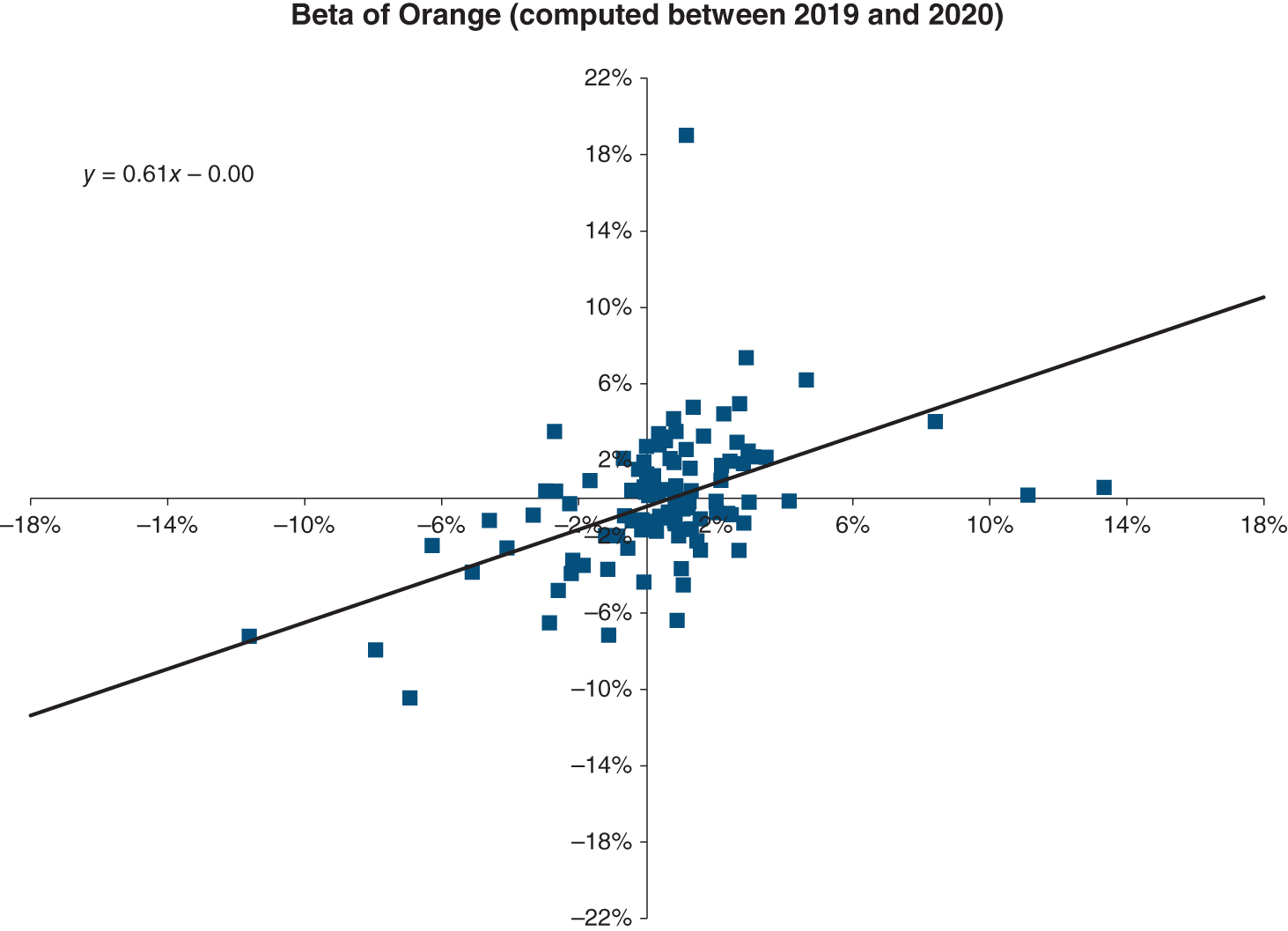

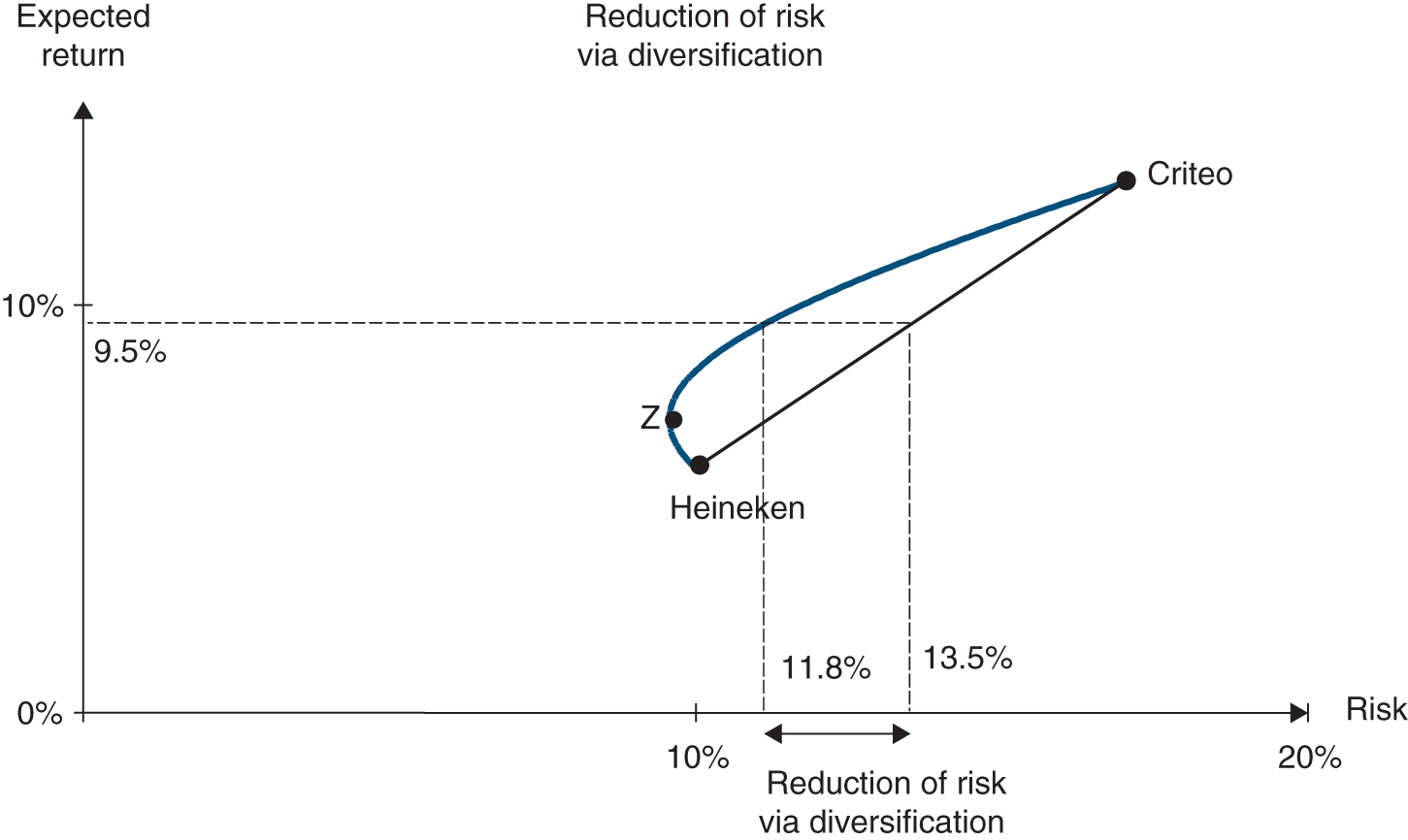

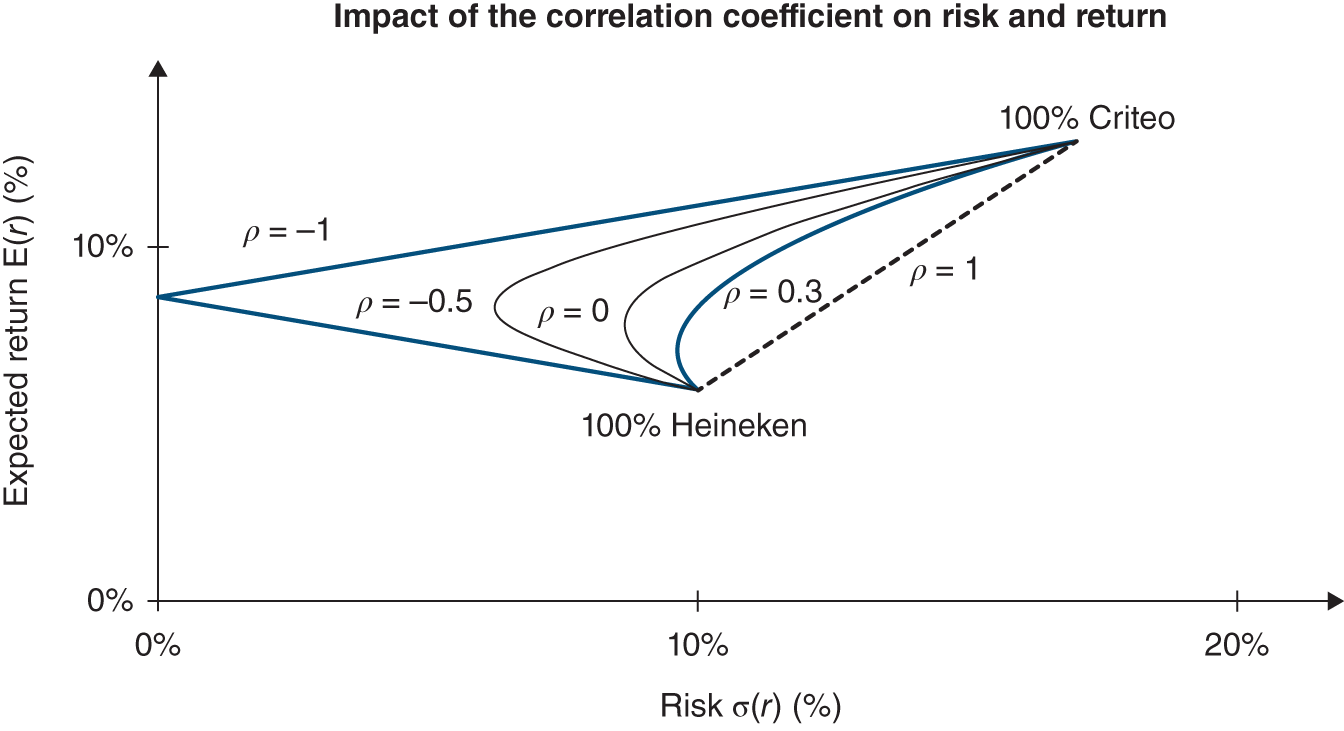

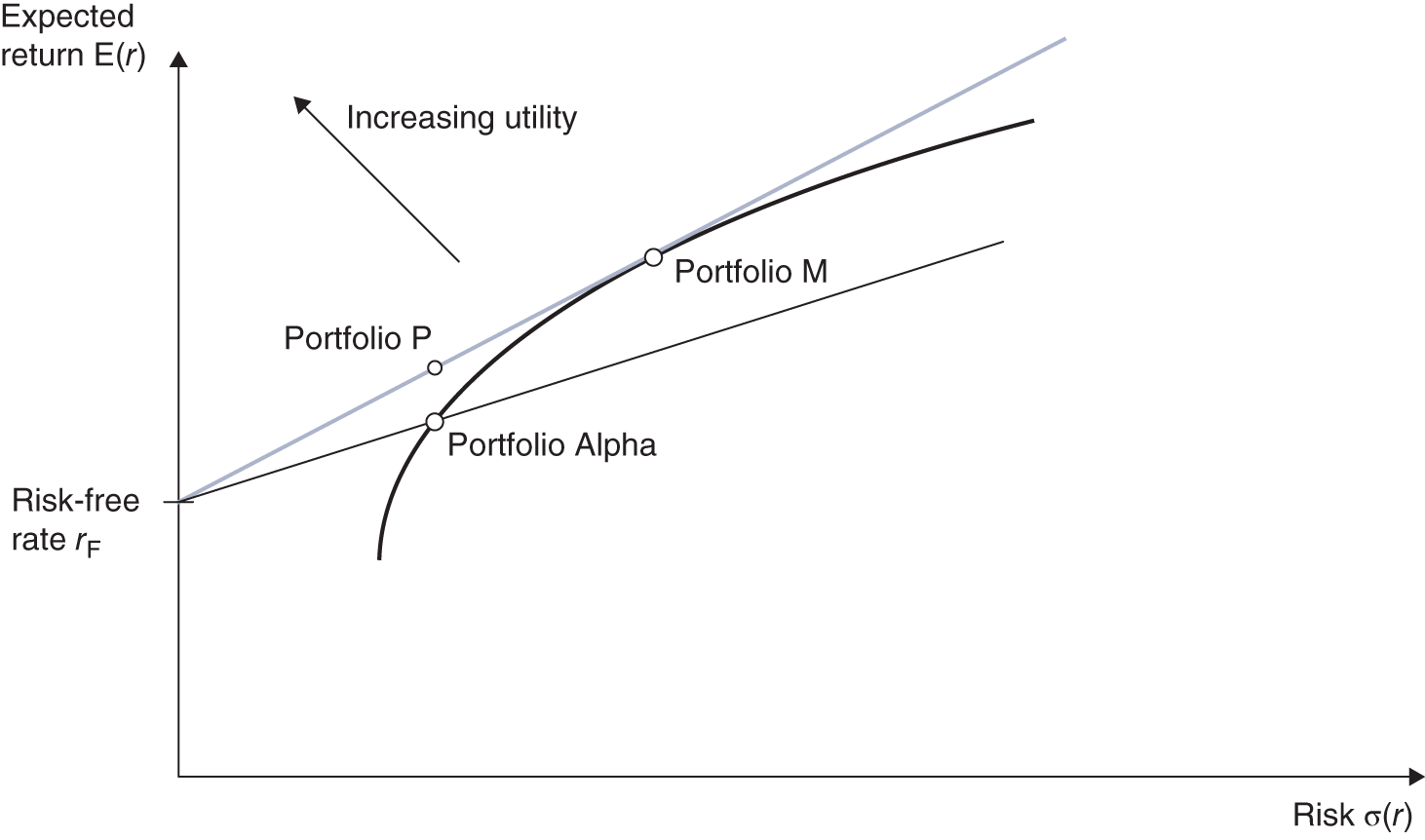

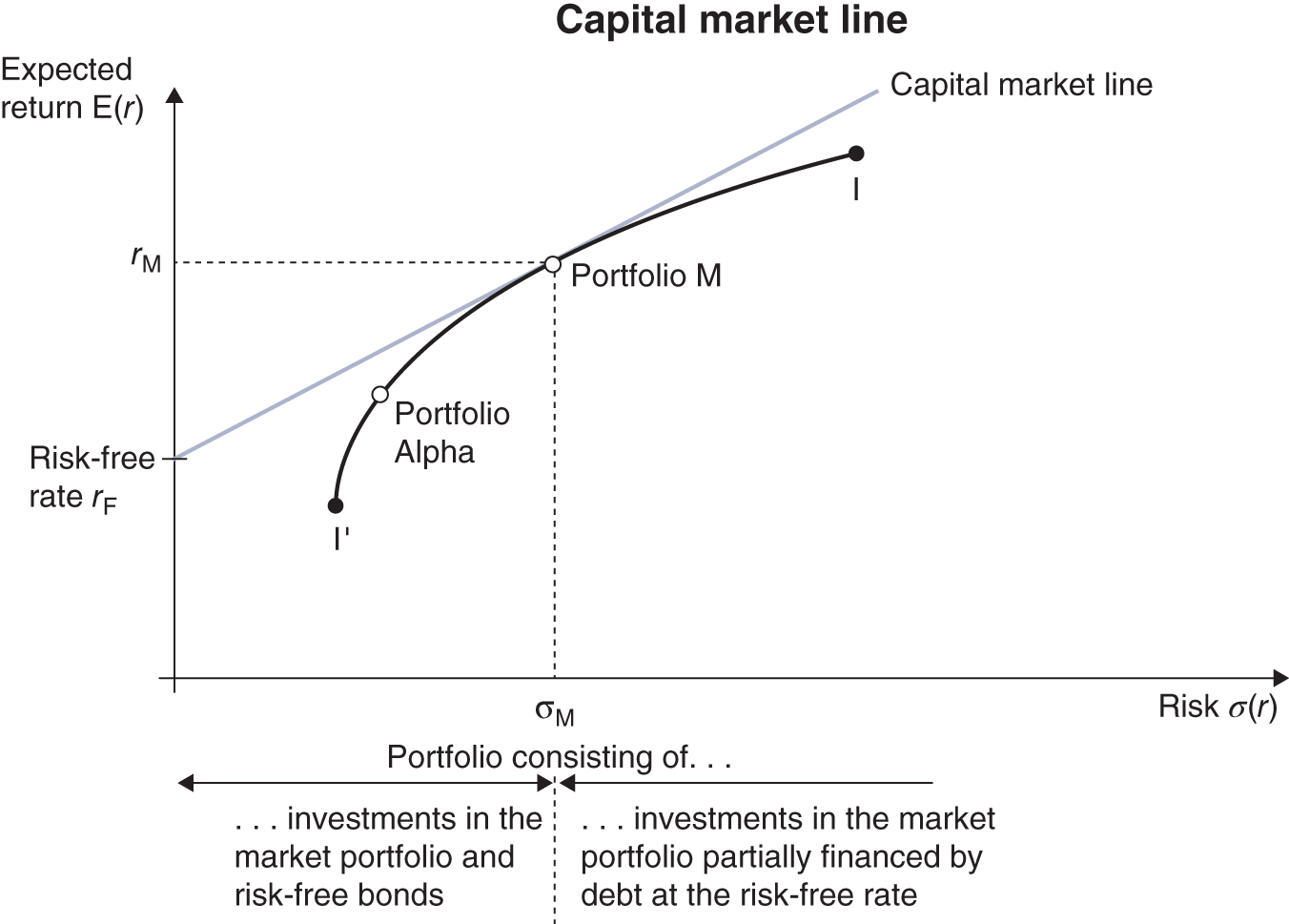

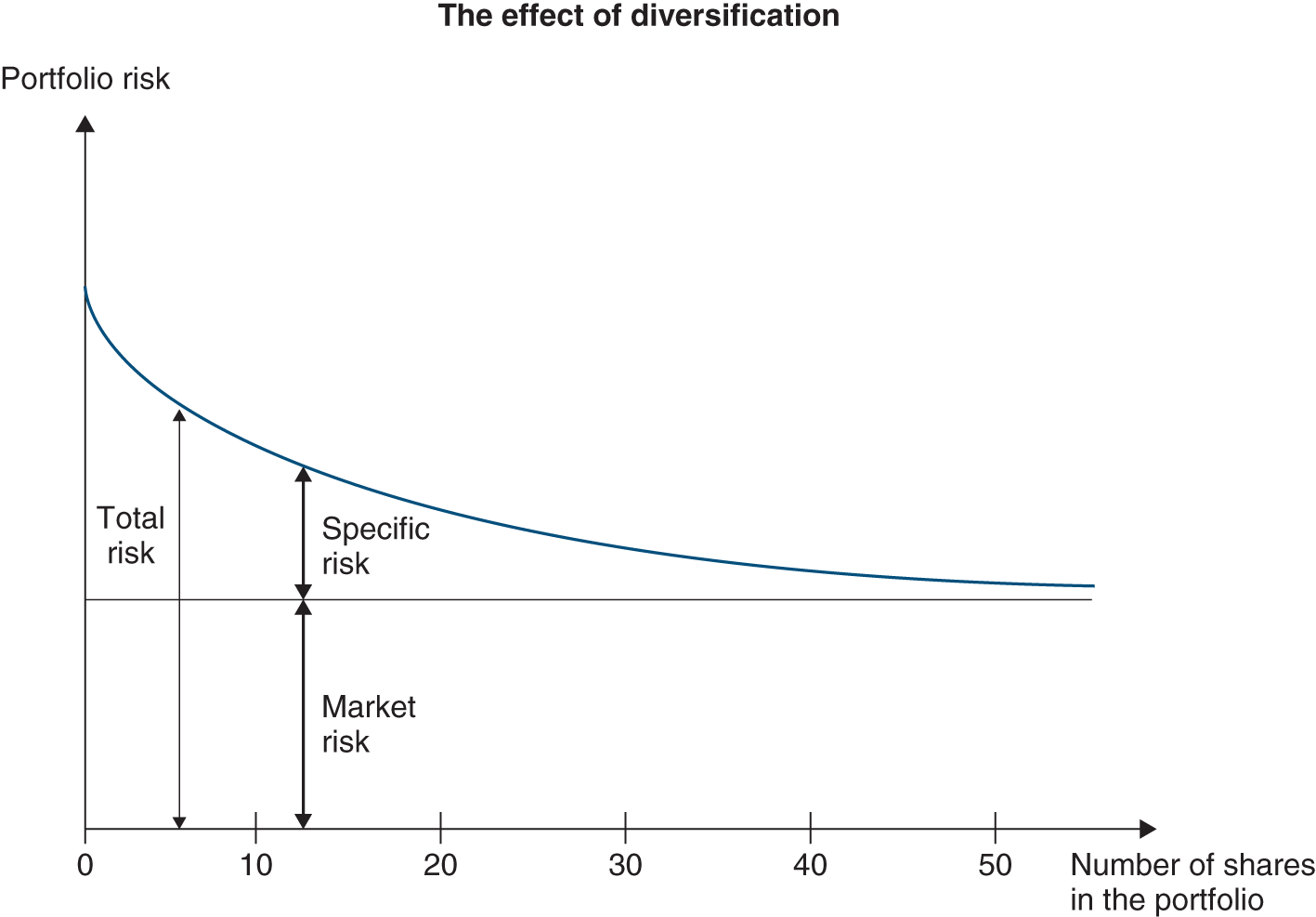

Section II reviews the basic theoretical knowledge you will need to make an assessment of the value of the firm. Here again, the emphasis is on reasoning, which in many cases will become automatic (Chapters 15): efficient capital markets, the time value of money, the price of risk, volatility, arbitrage, return, portfolio theory, present value and future value, market risk, beta, etc. Then we review the major types of financial securities: equity, debt and options, for the purposes of valuation, along with the techniques for issuing and placing them (Chapters 20).

Section III, is devoted to value, to its theoretical foundations and to its computation. Value is the focus of any financier, both its measure and the way it is shared. Over the medium term, creating value is, most of the time, the first aim of managers (Chapters 26).

In Section IV, “Corporate financial policies”, we analyse each financial decision in terms of:

- value in the context of the theory of efficient capital markets;

- balance of power between owners and managers, shareholders and debtholders (agency theory);

- communication (signal theory).

Such decisions include choosing a capital structure, investment decisions, cost of capital, dividend policy, share repurchases, capital increases, hybrid security issues, etc.

In this section, we draw your attention to today’s obsession with earnings per share, return on equity and other measures whose underlying basis we have a tendency to forget and which may, in some cases, be only distantly related to value creation. We have devoted considerable space to the use of options (as a technique or a type of reasoning) in each financial decision (Chapter 32).

When you start reading Section V, “Financial management”, you will be ready to examine and take the remaining decisions: how to create and finance a start-up, how to organise a company’s equity capital and its governance, buying and selling companies, mergers, demergers, LBOs, bankruptcy and restructuring (Chapter 40). Lastly, this section presents working capital management, cash management, the management of the firm’s financial risks and its operational real estate assets (Chapter 49).

Last but not least, the epilogue addresses the question of the links between finance and strategy.

Suggestions for the reader

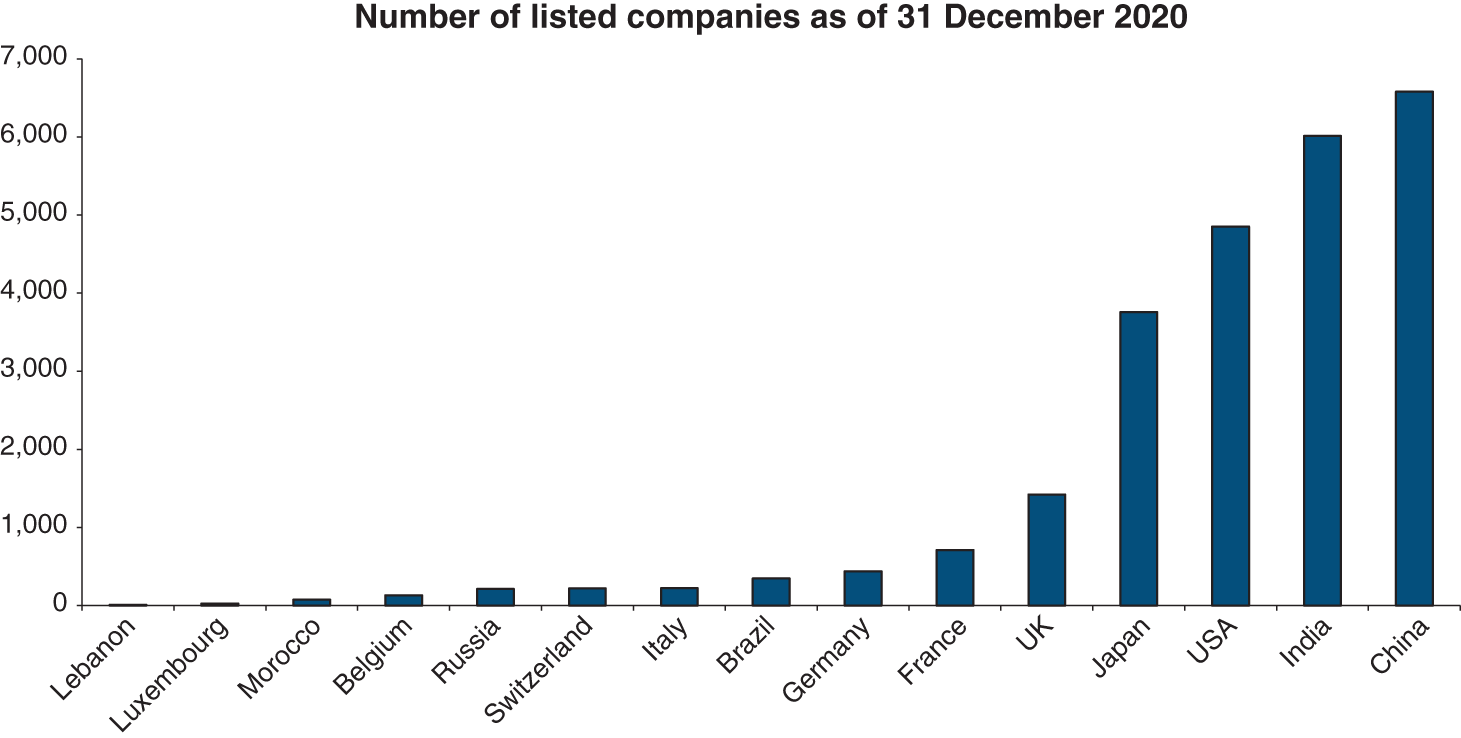

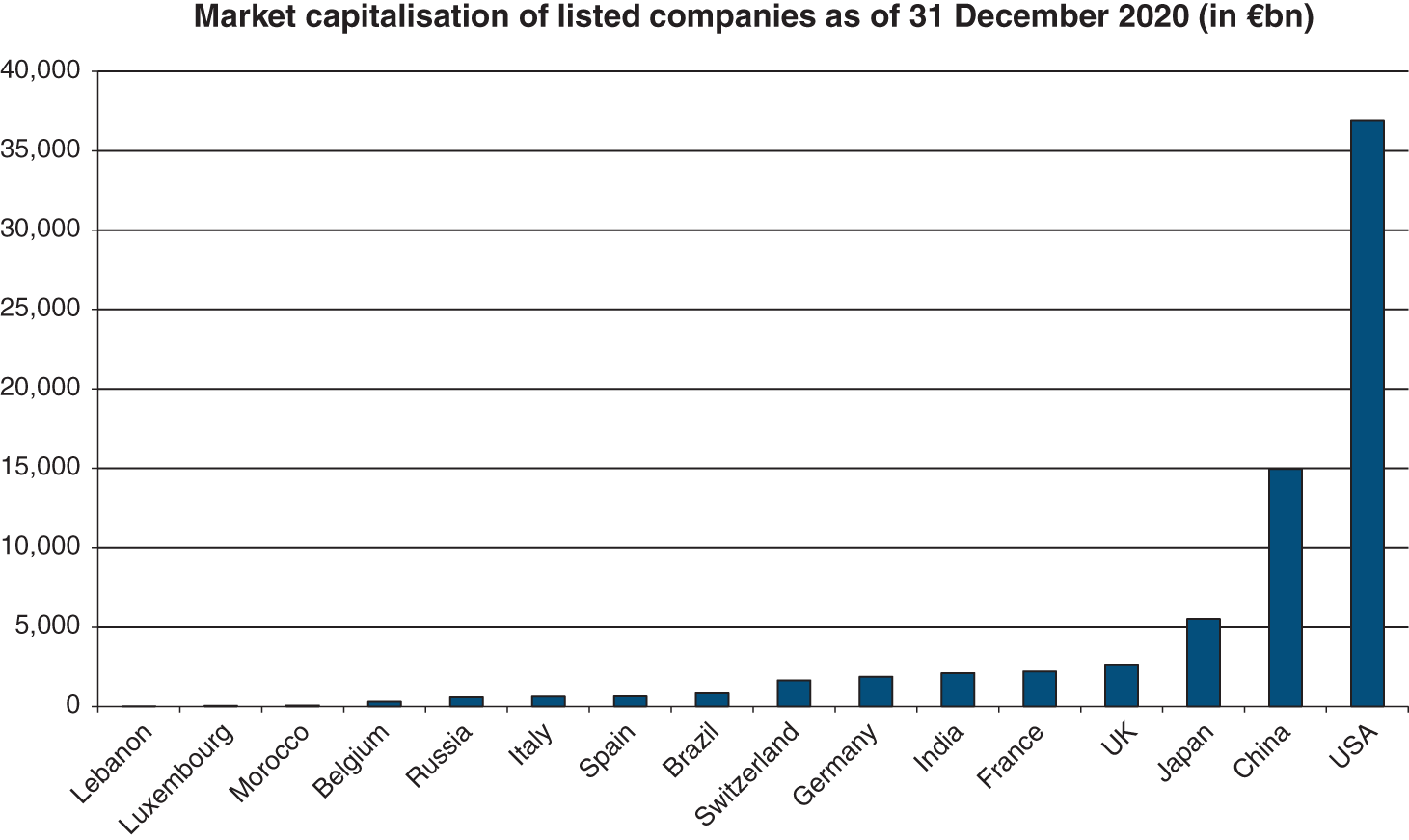

To make sure that you get the most out of your book, each chapter ends with a summary and a series of problems and questions (over 800 with the solutions provided). We’ve used the last page of the book to provide a crib sheet (the nearly 1,000 pages of this book summarised on one page!). For those interested in exploring the topics in greater depth, there is an end-of-chapter bibliography and suggestions for further reading, covering fundamental research papers, articles in the press, published books and websites. A large number of graphs and tables (over 100!) have been included in the body of the text and these can be used for comparative analyses. Finally, there is a fully comprehensive index.

An Internet site with huge and diversified content

www.vernimmen.com provides free access to tools (formulas, tables, statistics, lexicons, glossaries); resources that supplement the book (articles, prospectuses of financial transactions, financial figures for over 16,000 European, North American and emerging countries, listed companies, thesis topics, thematic links, a list of must-have books for your bookshelf, an Excel file providing detailed solutions to all of the problems set in the book); plus problems, case studies and quizzes for testing and improving your knowledge. There is a letterbox for your questions to the authors (we reply within 72 hours, unless, of course, you manage to stump us!). There are questions and answers and much more. The site has its own internal search engine, and new services are added regularly.

A teachers’ area provides teachers with free access to case studies, slides and an Instructor’s Manual, which gives advice and ideas on how to teach all of the topics discussed in the book.

A free monthly newsletter on corporate finance

Since (unfortunately) we can’t bring out a new edition of this book every month, we have set up the Vernimmen.com Newsletter, which is sent out free of charge to subscribers via the web. It contains:

- A conceptual look at topical corporate finance problems (e.g. accounting for operating and capital leases, financially managing during a deflation phase).

- Statistics and tables that you are likely to find useful in the day-to-day practice of corporate finance (e.g. corporate income tax rates, debt ratios in LBOs).

- A critical review of a financial research paper with a concrete dimension (e.g. the real effect of corporate cash, why don’t US issuers demand European fees for their IPOs?).

- A question left on the vernimmen.com site by a visitor plus a response (e.g. Why do successful groups have such a low debt level? What is an assimilation clause?).

- A catch up of our last posts on LinkedIn and Facebook.

Subscribe to www.vernimmen.com and become one of the many readers of the Vernimmen.com Newsletter.

And lastly a LinkedIn and Facebook page

We publish daily comments on financial news that we deem to be of interest, answer questions from web-users and publish finance- and business-related quotes. These could come in useful when preparing for a job interview or serve as food for thought for those of you wanting to take time out and think about what’s going on in the corporate and financial world.

Many thanks

- To Maurizio Dallocchio and Antonio Salvi, our co-authors of the previous editions (whose many hectic activities have led them to be unable to participate in the current work).

- To Patrice Carlean-Jones, Matthew Cush, Anthony de Rauville, Sandra Dupouy, Robert Killingsworth, Franck Megel, François Meunier, Pascale Mourvillier, John Olds, Françoise Quiry, Pierre Quiry, Gita Roux, Steven Sklar, Marc Vermeulen, Julie Watremez and students of the HEC Paris for their help in improving the manuscript since its inception.

- To Gemma Valler and Purvi Patel, our editors, to Elaine Bingham, Manikandan Kuppan and for their help to improve the manuscript.

- To Altimir Perrody, the vernimmen.com webmaster.

- Our colleagues at Natixis New York and HEC, in particular Blaise Allaz, Olivier Bossard, Lily Cheung, Paul Monange, Michael Moravec, Yohan Quere, Alessandra Rey and Robert White.

- Thanks to the BNP Paribas Chair in Corporate Finance at HEC Paris for its support.

- And last but not least to Françoise and Anne-Valérie; our children Paul, Claire, Pierre, Philippe, Soazic, Solène and Aymeric and our many friends who have had to endure our endless absences over the last years, and of course Catherine Vernimmen and her children for their everlasting and kind support.

We hope that you will gain as much enjoyment from your copy of this book – whether you are a new student of corporate finance or are using it to revise and hone your financial skills – as we have had in editing this edition and in expanding the services and products that go with it.

We wish you well in your studies!

Paris, New York, December 2021

Pascal Quiry Yann Le Fur

Frequently used symbols

| $A^N_k$ | Annuity factor for N years and an interest rate of k |

| ABCP | Asset-Backed Commercial Paper |

| ADR | American Depositary Receipt |

| AGM | Annual General Meeting |

| APT | Arbitrage Pricing Theory |

| APV | Adjusted Present Value |

| BIMBO | Buy-In Management Buy-Out |

| BV | Book Value |

| BV/S | Book Value per Share |

| CAGR | Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| Capex | Capital Expenditures |

| CAPM | Capital Asset Pricing Model |

| CB | Convertible Bond |

| CD | Certificate of Deposit |

| CE | Capital Employed |

| CFROI | Cash Flow Return On Investment |

| COV | Covariance |

| CVR | Contingent Value Right |

| D | Debt, net financial and banking debt |

| d | Payout ratio |

| DCF | Discounted Cash Flows |

| DDM | Dividend Discount Model |

| DECS | Debt Exchangeable for Common Stock; Dividend Enhanced Convertible Securities |

| Div | Dividend |

| DPS | Dividend Per Share |

| EBIT | Earnings Before Interest and Taxes |

| EBITDA | Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation |

| ECP | European Commercial Paper |

| EGM | Extraordinary General Meeting |

| EMTN | Euro Medium-Term Note |

| ENPV | Expanded Net Present Value |

| EONIA | Euro OverNight Index Average |

| EPS | Earnings Per Share |

| E(r) | Expected return |

| ESOP | Employee Stock Ownership Programme |

| Euribor | Euro Interbank Offered Rate |

| EV | Enterprise Value |

| EVA | Economic Value Added |

| f | Forward rate |

| F | Cash flow |

| FA | Fixed Assets |

| FASB | Financial Accounting Standards Board |

| FC | Fixed Costs |

| FCF | Free Cash Flow |

| FCFE | Free Cash Flow to Equity |

| FCFF | Free Cash Flow to Firm |

| FE | Financial Expenses |

| FIFO | First In, First Out |

| FRA | Forward Rate Agreement |

| g | Growth rate |

| GAAP | Generally Accepted Accounting Principles |

| GDR | Global Depositary Receipt |

| i | After-tax cost of debt |

| IAS | International Accounting Standards |

| IASB | International Accounting Standards Board |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standard |

| IPO | Initial Public Offering |

| IRR | Internal Rate of Return |

| IRS | Interest Rate Swap |

| IT | Income Taxes |

| k | Cost of capital, discount rate |

| kD | Cost of debt |

| kE | Cost of equity |

| K | Option strike price |

| LBO | Leveraged Buyout |

| LBU | Leveraged Build-Up |

| L/C | Letter of Credit |

| LIBOR | London Interbank Offered Rate |

| LIFO | Last In, First Out |

| LMBO | Leveraged Management Buyout |

| ln | Naperian logarithm |

| LOI | Letter Of Intent |

| m | Contribution margin |

| MOU | Memorandum Of Understanding |

| MTN | Medium-Term Notes |

| MVA | Market Value Added |

| n | Years, periods |

| N | Number of years |

| N(d) | Cumulative standard normal distribution |

| NA | Not Available |

| NAV | Net Asset Value |

| NM | Not Meaningful |

| NOPAT | Net Operating Profit After Tax |

| NPV | Net Present Value |

| OTC | Over The Counter |

| P | Price |

| PBO | Projected Benefit Obligation |

| PBR | Price-to-Book Ratio |

| PBT | Profit Before Tax |

| P/E ratio | Price/Earnings ratio |

| PEPs | Personal Equity Plans |

| PERCS | Preferred Equity Redemption Cumulative Stock |

| PSR | Price-to-Sales Ratio |

| P-to-P | Public-to-Private |

| PV | Present Value |

| PVI | Present Value Index |

| QIB | Qualified Institutional Buyer |

| r | Rate of return, interest rate |

| rF | Risk-free rate |

| rM | Expected return of the market |

| RNAV | Restated Net Asset Value |

| ROA | Return On Assets |

| ROCE | Return On Capital Employed |

| ROE | Return On Equity |

| ROI | Return On Investment |

| RWA | Risk-Weighted Assessment |

| S | Sales |

| SEC | Securities and Exchange Commission |

| SEO | Seasoned Equity Offering |

| SPV | Special Purpose Vehicle |

| STEP | Short-Term European Paper |

| t | Time |

| T | Time remaining until maturity |

| Tc | Corporate tax rate |

| TSR | Total Shareholder Return |

| UCITS | Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities |

| V | Value |

| VD | Value of Debt |

| VE | Value of Equity |

| V(r) | Variance of return |

| VAT | Value Added Tax |

| VC | Variable Cost |

| WACC | Weighted Average Cost of Capital |

| WC | Working Capital |

| y | Yield to maturity |

| YTM | Yield To Maturity |

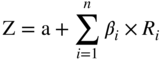

| Z | Scoring function |

| ZBA | Zero Balance Account |

| β or βE | Beta coefficient for a share or an equity instrument |

| βA | Beta coefficient for an asset or unlevered beta |

| βD | Beta coefficient of a debt instrument |

| σ(r) | Standard deviation of return |

| ρ(A, B) | Correlation coefficient of return between shares A and B |

Chapter 1. TOWARDS A GREEN, RESPONSIBLE AND SUSTAINABLE CORPORATE FINANCE

Trailer for a changing world…

The primary role of the financial manager is to ensure that their company has a sufficient supply of capital.

The financial manager or CFO (chief financial officer) is at the crossroads of the real economy, with its industries and services, and the world of finance, with its various financial markets and structures.

They also have two other roles: that of a controller of the risks and commitments made by the company, thereby ensuring its sustainability; and that of a strategist, which can make them invaluable to the executive.

The financial manager operates in an environment that is undergoing irreversible change due to growing environmental, social and governance concerns within the company. This change is naturally and durably affecting corporate finance, strongly since 2017–2018, and at a speed that has accelerated considerably in 2020–2021.

We believe that this development in corporate finance is so important that we will discuss it in the first three sections of this introductory chapter, before returning to the functions of the CFO, who has a part to play in the area of energy and social transition.

Section 1.1 AN UNPRECEDENTED CHANGE UNDERWAY

The years between 2015 and 2020 saw an irreversible upswing in concern for the environment, social responsibility and sustainability in finance, and in particular in corporate finance, to such an extent that we predict, in a slightly pretentious way, that corporate finance will in the future be green, responsible and sustainable, or it will not be at all!

1/ SOME EMBLEMATIC FACTS

Here are some recent facts, among others, which illustrate this acceleration in ecological, social and sustainable awareness in the financial world:

- Financial analysts from the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, Norway’s oil fund, which manages around €1,133bn, are now accompanied by environmental, social and governance (ESG) analysts when they hold meetings with managers of any of the 9,123 companies in which the fund is a shareholder or is considering becoming one;

- Danone (in 2020) and Kering are now presenting new financial tools (decarbonised earnings per share for Danone and environmental income statement for Kering) to measure the impact of the group on carbon emission or environment;

- In 2018, the CEO of Blackrock – the largest asset manager in the world with close to €7,400bn in assets under management – wrote in the annual letter to the CEOs of major groups worldwide in which Blackrock has invested money:

- “Society is demanding that companies, both public and private, serve a social purpose. To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate”.

- As early as 2016, Larry Finck wrote in his annual letter to the CEOs: “Over the long term, environmental, social and governance issues – from climate change to diversity and including board efficiency – have real and quantifiable financial impacts.”

- In March 2018, the European Commission published its “strategy to bring the financial system to support the European Union’s climate and sustainable development agenda”, which will involve:

- “– establishing a common language for sustainable finance, i.e. a unified EU classification system – or taxonomy – to define what is sustainable and identify areas where sustainable investment can make the biggest impact;

- – creating EU labels for green financial products on the basis of this EU classification system: this will allow investors to easily identify investments that comply with green or low-carbon criteria;

- – clarifying the duty of asset managers and institutional investors to take sustainability into account in the investment process and enhance disclosure requirements;

- – requiring insurance and investment firms to advise clients on the basis of their preferences on sustainability;

- – incorporating sustainability in prudential requirements: banks and insurance companies are an important source of external finance for the European economy. The Commission will explore the feasibility of recalibrating capital requirements for banks (the so-called green supporting factor) for sustainable investments, when it is justified from a risk perspective, while ensuring that financial stability is safeguarded;

- – enhancing transparency in corporate reporting: we propose to revise the guidelines on non-financial information to further align them with the recommendations of the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).”

- In 2019, a large European bank, Natixis, introduced a voluntary mechanism for the internal allocation of prudential capital, which lowers the cost of financing with a positive impact on the environment, to the detriment of financing with a negative impact, thus increasing its cost. Moreover, it directs its commitments towards actors with a positive approach in this area.

2/ OLD OR RECENT ROOTS

We may well wonder why this is happening now and not five or ten years ago, or in four to five years’ time. It’s difficult to say. Like all groundswell movements, it started as the result of several factors, has been developing gradually and slowly over time and now that has gained momentum, it’s shaking up the whole system.

Environmental urgency is another factor: the depletion of the earth’s resources, which may well turn out to be a surmountable problem given human ingenuity, and global warming, which it is to be feared may well be a problem that we have underestimated.

It is undeniable that the 2007–2008 financial crisis had a major impact on how we see the world, probably more so than any other financial crisis, apart from the 1929 crisis. It naturally impacted on the way finance directors exercise financial management.1 It also had a major impact on the general public who discovered that a financial product, sub-primes,2 involved getting clients to borrow more than what was reasonable while getting others to take on the risk in order to get rich at their expense, with no regard for the consequences. This is now seen as morally unacceptable. Never again.

Finally, a disenchantment with ideologies and the growing difficulties that governments are experiencing in maintaining their traditional post-World War II roles of protector and distributor of resources, mean that individuals are now seeking meaning in what they spend most of their lives doing, which is working. Young people in particular want a mission in life and not a job, a mentor rather than a boss, and they want to make an impact and see meaning in what they do. Today, a lot more is expected from companies than in the past. More and more corporate people think that the company has a purpose and that it contributes to the common interest.

Without being cynical, we should also not overlook the phenomenon of lemming behaviour which is something we’re very familiar with in the world of finance. Companies seem to be competing against each other in the increasingly ambitious ESG statements that they put out. This is not cause for complaint, but now they’re going to have to deliver.

Section 1.2 A DECISIVE IMPETUS FROM INVESTORS

What concrete forms does all this take?

Among investors, concerns about socially responsible investment (SRI) first arose in the 18th century in religious communities (Quakers, Methodists), which forbade their members from investing in companies that produced weapons, alcohol or tobacco.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria have emerged to enable investors wishing to work towards this goal to select the companies they consider to be the most virtuous in these areas. They constitute the three pillars of extra-financial analysis that complement the financial analysis of the accounts that we present in Section I of this book:

- The environmental criterion covers the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the recycling of waste, the management of scarce resources (raw materials, water, etc.) and the prevention of environmental risks.

- The social criterion takes into account accident prevention, staff training, respect for employee rights, employment of disabled people, management of the subcontracting chain, and more generally the quality of social dialogue.

- The governance criterion mainly covers the independence of the board of directors, the company’s management structure, the transparency of executive compensation, the fight against corruption, and the increase in the number of women on the board of directors and the executive committee. It is detailed in Chapter 43.

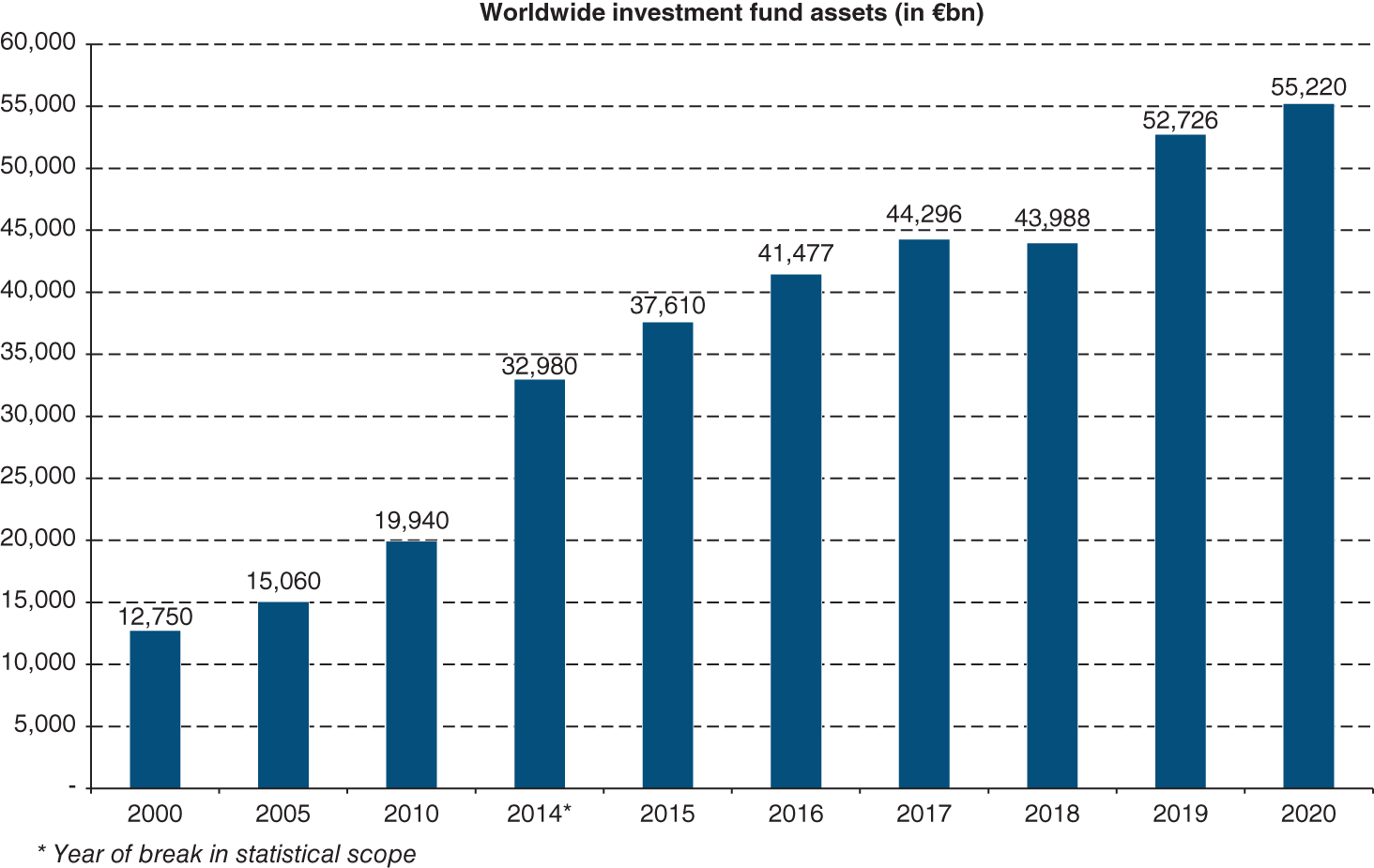

Around $30,700bn is managed around the world using ESG criteria,3 i.e. a third of all financial assets under management but 49% in Europe, which is leading the world in this field. The strategies implemented are more or less intense: the Best in Class strategy advocates investing within a sector in the best performing companies from an ESG point of view; the Best Effort strategy is less radical in its selection because it includes more broadly the companies with the best ESG progress. The norm-based screening strategy sets minimum ESG standards for a company to be included in a portfolio.

Some investors wish to go further and have developed SRI (socially responsible investment) defined as “an investment that aims to achieve a social and environmental impact by financing companies and public entities that contribute to sustainable development regardless of their sector of activity. By influencing the governance and behaviour of stakeholders, SRI encourages a responsible economy.”4

In the field of unlisted investments, impact funds aim to generate a positive social and environmental impact in addition to a financial return. The remuneration of their managers is linked to the achievement of predetermined non-financial objectives.

In Section 8.2, 4/, we maintain that from a strictly financial point of view, the most important men and women in a company are its shareholders. SRI is an illustration of this as by overweighting or underweighting certain companies in their portfolios (or even totally eliminating them) investors, like other stakeholders, exercise media and financial pressure on these companies, making them more expensive to finance, leading in the long run to a reduction in their activities.

In May 2021, Engine No. 1 – a small American investment fund with a 0.02% stake in ExxonMobil (market capitalisation of €200bn) – succeeded in rallying the majority of the American oil company’s shareholders to elect as directors three people who wanted ExxonMobil to initiate its energy transition, as opposed to three other candidates who were in favour of the status quo and who were supported by the management.

Although there have long been doubts about the compatibility of responsible investment with financial performance, a number of empirical studies have shown that SRI funds achieve identical or better performances than conventional funds. A Russel Investment5 study shows that asset managers that create the most value already have a large number of stocks that comply with ESG criteria in their portfolios.

Section 1.3 BUSINESS BEHAVIOUR AND THEIR FINANCING ARE GRADUALLY CHANGING

Under pressure from investors and society in general, companies are becoming aware of their corporate social responsibility (CSR), defined, for example, by the European Union as: “The voluntary integration of social and environmental concerns by companies into their business activities and their relations with their stakeholders. Being socially responsible means not only fully complying with applicable legal obligations, but also going beyond them and investing ‘more’ in human capital, the environment and stakeholder relations.”

1/ THE EMERGENCE OF GREEN AND RESPONSIBLE FINANCING

When it comes to financing of companies, volumes of green or sustainable financing are still marginal at this stage, but have increased sharply. Today we get green bonds (Section 20.4), green loans (Section 21.2) and social bonds (Section 20.4).

Green bonds are conventional bonds in terms of their financial flows so the innovation here is not financial! Their green status stems from the issuer’s undertaking to use the funds for investing or spending that is positive for the environment (as defined by the company, which is generally assisted by an independent firm). Social bonds finance socially responsible projects.

Monitoring spending and allocating a source of financing to a particular use requires a specific type of organisation that financial departments are not accustomed to. And it has a cost, borne by companies as long as investors are not prepared to pay more for green bonds than for conventional bonds.

Standards for green, social and more generally responsible bonds are established by the ICMA,6 which publishes the Green Bonds Principles and Social Bonds Principles. This is important as investors rely on these standards in order to demonstrate that their investments are SRI compliant and that these bonds are eligible for inclusion in their funds or their asset portfolios dedicated to such investments.

Companies have another financial tool they can use for ESG policy implementation: green or responsible revolving credit facilities (RCFs7). Unlike bonds, these facilities do not require funds to be used for ESG projects (this would be complicated as for large groups, these facilities are mostly back-up undrawn credit lines). Their ESG aspect comes from the fact that their cost (and thus the banks’ remuneration) depends on the company achieving ESG goals. The relevance of these goals is initially validated by an independent agency and is subject to monitoring while the credit facility is active. We note that these products entail an ESG cost both for the company and the bank financing it! At this stage, the variability of the credit margin, which is dependent on whether the ESG goals are achieved or not, is still only a few basis points.

Notwithstanding the above, ESG-type financing products are also used to mobilise employees internally given that ESG goals become more concrete since failing to achieve them results in a (small) financial penalty and has a psychological impact that is certainly not negligible.

2/ ESG STANDARDS ARE NOT YET STABILISED

This development has brought its own problems. How do we go about assessing, rating and ranking companies on the basis of ESG criteria? What are the most relevant criteria and for whom are they relevant? Clearly, assessments should be sector-based as an agri-food business will not face the same ESG challenges as a power generating company. Agencies that rate companies on the basis of their ESG policies (Vigeo Eiris, Cicero and Sustainalytics) are emerging, the traditional rating agencies and audit firms are also seeking to get in on the act as are the certification agencies (Bureau Veritas, SGS) while standards (ISO) will soon be developed.

One of the problems that companies are having to face remains the lack of a uniform and dynamic method for selecting these criteria. New criteria are continually arising (sometimes in response to the latest trends or because new controversies have emerged) and companies are having to be agile if they want to hang onto their ratings or certifications.

One of the problems raised by green or social bonds is that funds raised must be used for ESG investments. This means they are easy to issue for very capital-intensive businesses (energy, real estate, etc.), but much trickier for knowledge-based industries (what sort of investment by an advertising agency could be classified as green or social?) So, in today’s world, these companies are unable to make use of this tool even if they happen to have impeccable ESG credentials.

This highlights the difference between the holistic and the targeted project approach to ESG. The former is clearly more ambitious but difficult to measure, standardise and grasp for anyone outside the company. There is the fear that companies may indulge in communication one-upmanship and greenwashing without taking any real action, all in the interests of political correctness. The latter approach is more concrete for investors, but involves a risk of financing companies that generally do not have very impressive ESG ambitions and only communicate on a few projects.

3/ A TOUGH CONSTRAINT

But let’s not deceive ourselves. This is most definitely not just a passing trend to which homage should be paid for a short time, before returning to the way we used to do things in the good (or rather bad) old days!

The good news is that the long-term view doesn’t seem to be exclusively focused on financial performance. From the point of view of companies, the Boston Consulting Group8 shows that, out of a sample of 343 groups in 5 sectors, companies with a high ESG score have higher margins than others. The direction of causality still needs to be determined. The fact that companies with higher ethical standards are more attractive to employees is one explanation. Other explanations also highlight better risk management as a result of ESG issues being factored in and the creation of opportunities. As an example, ArcelorMittal has announced that a new technology for treating gas produced by its Gand plant will enable it to transform gas into bio-ethanol that it will be able to sell.

Section 1.4 THE THREE ROLES OF THE FINANCIAL MANAGER

While the primary role of the corporate financial manager is to be responsible for the provision of capital to the company, they also have a role in monitoring profitability and risk, which ensures sustainability, and the ESG commitments made to the investors who finance the company. The best of them are also strategists.

1/ THE FINANCIAL MANAGER IS FIRST AND FOREMOST A SALESPERSON AND A NEGOTIATOR

(a) The financial manager’s job is not only to “buy” financial resources …

Financial managers are traditionally perceived as buyers of capital. They negotiate with a variety of investors – bankers, shareholders, bond investors – to obtain funds at the lowest possible cost.

Transactions that take place on the capital markets are made up of the following elements:

- a commodity: money;

- a price: the interest rate in the case of debt; dividends and capital gains in the case of equities.

In the traditional view, financial managers re responsible for the company’s financial procurement. Their job is to minimise the price of the commodity to be purchased, i.e. the cost of the funds they raise.

We have no intention of contesting this view of the world. It is obvious and is confirmed every day, in particular in the following types of negotiations:

- between corporate treasurers and bankers, regarding interest rates and value dates applied to bank balances (see Chapter 50);

- between CFOs and financial market intermediaries, where negotiation focuses on the commissions paid to arrangers of financial transactions (see Chapter 25).

(b) … but also to sell financial securities

That said, let’s now take a look at the financial manager’s job from a different angle:

- they are not a buyer but a seller;

- their aim is not to reduce the cost of the raw material they buy but to maximise a selling price;

- they practise their art not on the capital markets, but on the market for financial instruments, be they loans, bonds, shares, etc.

We are not changing the world here; we are merely looking at the same market from another point of view:

- the supply of financial securities corresponds to the demand for capital;

- the demand for financial securities corresponds to the supply of capital;

- the price, the point at which the supply and demand for financial securities are in equilibrium, is therefore the value of security. In contrast, the equilibrium price in the traditional view is considered to be the interest rate, or the cost of funds.

We can summarise these two ways of looking at the same capital market in the following table:

| Analysis/Approach | Financial approach: financial manager as seller | Traditional approach: financial manager as purchaser |

|---|---|---|

| Market | Securities | Capital |

| Supply | Issuers | Investors |

| Demand | Investors | Issuers |

| Price | Value of security | Interest rate |

Depending on your point of view, i.e. traditional or financial, supply and demand are reversed, as follows:

- when the cost of money – the interest rate, for example – rises, demand for funds is greater than supply. In other words, the supply of financial securities is greater than the demand for financial securities, and the value of the securities falls;

- conversely, when the cost of money falls, the supply of funds is greater than demand. In other words, the demand for financial instruments is greater than their supply and the value of the securities rises.

For two practical reasons, one minor and one major, we prefer to present the financial manager as a seller of financial securities.

The minor reason is that viewing the financial manager as a salesperson trying to sell their products at the highest price casts their role in a different light. As the merchant does not want to sell low-quality products but products that respond to the needs of their customers, so the financial manager must understand and satisfy the needs of their capital suppliers without putting the company or its other capital suppliers at a disadvantage. The financial manager must sell high-quality products at high prices but can also repackage the product to better meet investor expectations. Indeed, financial markets are subject to fashion: in one period convertible bonds (see Chapter 24) can be easily placed; in another period it will be syndicated loans (see Chapter 21) that investors will welcome.

The more important reason is that when a financial manager applies the traditional approach of minimising the cost of the company’s financing too strictly, erroneous decisions may easily follow. The traditional approach can make the financial manager short-sighted, tempting them to take decisions that emphasise the short term to the detriment of the long term.

For instance, choosing between a capital increase, a bank loan and a bond issue with lowest cost as the only criterion reflects flawed reasoning. Why? Because suppliers of capital, i.e. the buyers of the corresponding instruments, do not all face the same level of risk.

The cost of two sources of financing can be compared only when the suppliers of the funds incur the same level of risk.

All too often we have seen managers or treasurers assume excessive risk when choosing a source of financing because they have based their decision on a single criterion: the respective cost of the different sources of funds. For example:

- increasing short-term debt on the pretext that short-term interest rates are lower than long-term rates can be a serious mistake;

- granting a mortgage in return for a slight decrease in the interest rate on a loan can be very harmful for the future;

- increasing debt systematically on the sole pretext that debt costs less than equity capital jeopardises the company’s prospects for long-term survival.

We will develop this theme further throughout the third part of this book, but we would like to warn you now of the pitfalls of faulty financial reasoning. The most dangerous thing a financial manager can say is, “It doesn’t cost anything.” This sentence should be banished and replaced with the following question: “What is the impact of this action on value?”

(c) Most importantly, the financial manager is a negotiator …

But what exactly is our financial manager selling? Or, put another way: how can the value of the financial security be determined?

From a practical standpoint, the financial manager “sells” management’s reputation for integrity, its expertise, the quality of the company’s assets, its overall financial health, its ability to generate a certain level of profitability over a given period and its commitment to more or less restrictive legal terms. Note that the quality of assets will be particularly important in the case of a loan tied to and often secured by specific assets, while overall financial health will dominate when financing is not tied to specific assets.

Theoretically, the financial manager sells expected future cash flows that can derive only from the company’s business operations.

A company cannot distribute more cash flow to its providers of funds than its business generates. A money-losing company pays its creditors only at the expense of its shareholders. When a company with sub-par profitability pays a dividend, it jeopardises its financial health.

The financial manager’s role is to transform the company’s commercial and industrial business assets and commitments into financial assets and commitments.

In so doing, they spread the expected cash flows among many different investor groups: banks, financial investors, family shareholders, individual investors, etc.

Financial investors then turn these flows into negotiable instruments traded on an open market, which values the instruments in relation to other opportunities available on the market.

Underlying the securities is the market’s evaluation of the company. A company considered to be poorly managed will see investors vote with their feet. Yields on the company’s securities will rise to prohibitive levels and prices on them will fall. Financial difficulties, if not already present, will soon follow. Financial managers must therefore keep the market convinced at all times of the quality of their company, because that is what backs up the securities it issues!

The different financial partners hold a portion of the value of the company. This diversity gives rise to yet another job for the financial manager: to adroitly steer the company through the distribution of the overall value of the company.

Like any dealmaker, the financial manager has something to sell, but must also:

- assess the company’s overall financial situation;

- understand the motivations of the various participants;

- analyse the relative powers of the parties involved.

2/ THE FINANCIAL MANAGER IS ALSO A CONTROLLER

(a) Of profitability as a guarantee of sustainability

The financial investors who buy the company’s securities do so not out of altruism, but because they hope to realise a certain rate of return on their investment, in the form of interest, dividends and/or capital gains. In other words, in return for entrusting the company with their money via their purchase of the company’s securities, they require a minimum return on their investment.

The financial manager must therefore analyse the different investment projects proposed by operational people and explain to colleagues that some should not be undertaken because they are not profitable enough compared to the return investors are looking for. In short, financial managers sometimes have to be “party-poopers”. They are indirectly the spokesperson of the financial investment community.

Consequently, the financial manager must make sure that over the medium term the company makes investments with returns at least equal to the rate of return expected by the company’s providers of capital. If so, all is well. If not, if the company is consistently falling short of this goal, then it will destroy value, turning what was worth 100 into 90, or 80. This is corporate purgatory. On the other hand, if the profitability of its investments consistently exceeds investor demands, transforming 100 into 120 or more, then the company deserves the kudos it will get. But it should also remain humble. With technological progress and deregulation advancing apace, repeat performances are becoming more and more challenging.

If the profitability over several years of the company’s operating assets is not at least equal to the return looked for by investors, then the financial manager should discuss how to improve the situation with operational people.

(b) Of risks run by the company

Fluctuations in interest rates, currencies and the prices of raw materials are so great that financial risks are as important as industrial risks. Consider a Swiss company that buys copper in the world market, then processes it and sells it in Switzerland and abroad.

Its performance depends not only on the price of copper but also on the exchange rate of the US dollar versus the Swiss franc, because it uses the dollar to make purchases abroad and receives payment in dollars for international sales. Lastly, interest rate fluctuations have an impact on the company’s financial flows. A multi-headed dragon!

The company must manage its specific interest rate and exchange rate risks because doing nothing can also have serious consequences (see Chapter 51).

Take an example of an economy with no derivative markets. A corporate treasurer anticipating a decline in long-term interest rates and whose company has long-term debt has no choice but to borrow short term, invest the proceeds long term, wait for interest rates to decline, pay off the short-term loans and borrow again. You will have no trouble understanding that this strategy has its limits. The balance sheet becomes inflated, intermediation costs rise, and so on. Derivative markets enable the treasurer to manage this long-term interest rate risk without touching the company’s balance sheet.

Generally, the CFO is responsible for the identification, the assessment and the management of risks for the firm. This includes not only currency and interest rate risks but also liquidity and counterparty risk. Recent years have shown that a CFO with strong know-how in such matters is highly appreciated.

(c) Of ESG commitments made by the company

As the spokesperson within the company for the investors who finance it, the role of the CFO is also to guarantee the sincerity of the ESG commitments made and their respect over time, because sincerity creates trust. And without trust, there is no funding.

3/ THE FINANCIAL MANAGER IS ALSO A STRATEGIST

The corporate financier is also a strategist who, because they constantly assess the risk and profitability of the company’s activities, and therefore, as we shall see, their value, is in a position to suggest a review of their scope. The company will thus be able to sell to better placed third parties, assets on which it is unable over time to generate the required rate of return in view of their risks, in order to concentrate on the best performing divisions that can be developed through acquisitions.

We are far from the CFOs of the sixties who were mainly top-of-the-class accountants! Nowadays they are required not only to perfectly master accounting and finance, but also to be gifted in marketing and negotiation, not to mention tax and legal issues, risk management, and to be able managers of their teams. The best of them also have a strategic way of thinking, and their intimate knowledge of the company and its human resources allows them to be serious candidates for the top job. As an illustration, the current CEOs of Siemens, Danone, Expedia, Sony and Tata Consulting are all former CFOs of their companies.

* * *

We’re going to leave you with these appetisers in the hope that you are now hungry for more. But beware of taking the principles briefly presented here and skipping directly to Section III of the book. If you are looking for high finance and get-rich-quick schemes, this book is definitely not for you. The menu we propose is as follows:

- First, an understanding of the firm, i.e. the source of all the cash flows that are the subject of our analysis (Section I: Financial analysis).

- Then an appreciation of markets, because it is they who are constantly valuing the firm (Section II: Investors and markets).

- Then an understanding of how value is created and how it is measured (Section III: Value).

- Followed by the major financial decisions of the firm, viewed in the light of both market theory, organisational and behavioural theories (Section IV: Corporate financial policies).

- Finally, if you persevere through the foregoing, you will get to taste the dessert, as Section V: Financial management presents several practical, current topics in financial engineering and management.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

- 1 See Chapter 39.

- 2 For our young readers, see the Vernimmen.com Newsletter, 28, 7–8, November 2007 or the film The Big Short.

- 3 2018 Global Sustainable Investment Review.

- 4 AFG, the French Association of Financial Management, grouping of professionals managing portfolios on behalf of third parties, and the Forum for Socially Responsible Investment.

- 5 Are ESG tilts consistent with value creation in Europe? January 2015.

- 6 International Capital Markets Association.

- 7 See Section 21.2.

- 8 Total societal impact, a new lens for strategy, October 2017.

**Section I. FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

****PART ONE. FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS IN FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

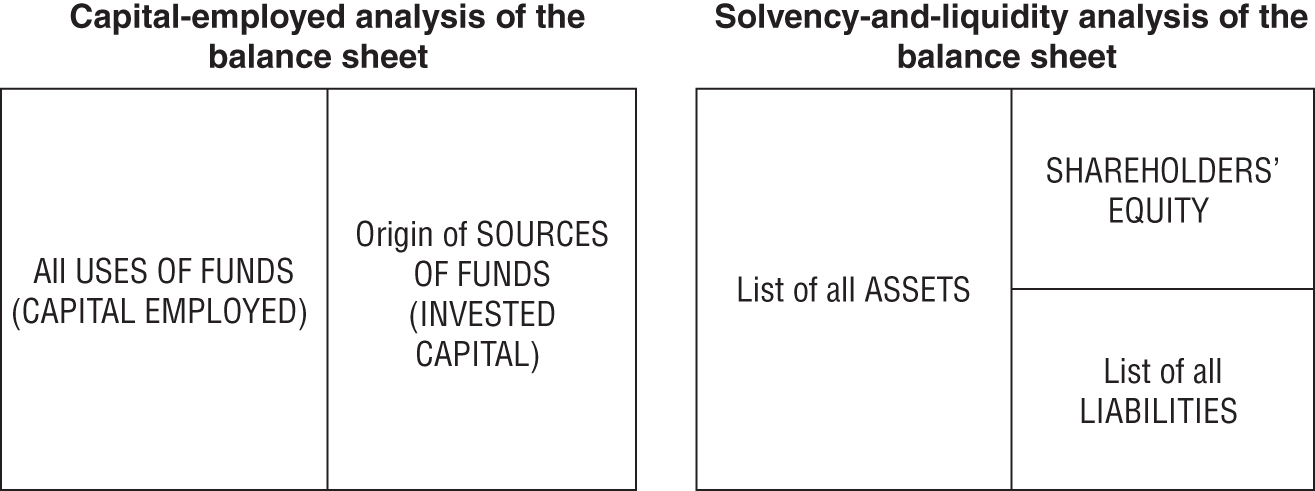

The following six chapters provide a gradual introduction to the foundations of financial analysis. They examine the concepts of cash flow, earnings, capital employed and invested capital, and look at the ways in which these concepts are linked.

They are fundamental for readers who have only a vague knowledge of the business world and basic accounting techniques. In this case, our advice is to read them and reread them before going further.

Chapter 2. CASH FLOW

Let’s work from A to Z (unless it turns out to be Z to A!)

Let’s begin our understanding of the business by analysing the cash flows that pre-exist any accounting or management system.

Section 2.1 CLASSIFYING COMPANY CASH FLOWS

Let’s consider, for example, the monthly account statement that individual customers receive from their bank. It is presented as a series of lines showing the various inflows and outflows of money on precise dates and the type of transaction (debit card payment or cash withdrawal, for instance).

Our first step is to trace the rationale for each of the entries on the statement, which could be everyday purchases, payment of a salary, automatic transfers, internet subscriptions, loan repayments or the receipt of bond interests, to mention a few examples.

The corresponding task for a financial manager is to reclassify company cash flows by category to draw up a cash flow document that can be used to:

- analyse past trends in cash flow (the document put together is generally known as a cash flow statement1); or

- project future trends in cash flow, over a shorter or longer period (the document needed is a cash flow budget or plan).

With this goal in mind, we will now demonstrate that cash flows can be classified into one of the following processes:

- Activities that form part of the industrial and commercial life of a company:

- operating cycle;

- investment cycle.

- Financing activities to fund these cycles:

- the debt cycle;

- the equity cycle.

Section 2.2 OPERATING AND INVESTMENT CYCLES

1/ THE IMPORTANCE OF THE OPERATING CYCLE

Let’s take the example of a greengrocer, Mr G, who is “cashing up” one evening. What does he find? First, he sees how much he spent in cash at the wholesale market in the morning and then the cash proceeds from fruit and vegetable sales during the day. If we assume that the greengrocer sold all the produce he bought in the morning at a mark-up, then the balance of receipts and payments for the day will be a cash surplus.

Unfortunately, things are usually more complicated in practice. It’s rare that all the goods bought in the morning are sold by the evening, especially in the case of a manufacturing business.

A company processes raw materials as part of an operating cycle, the length of which varies tremendously, from a day in the newspaper sector to seven years in the cognac sector. There is, then, a time lag between purchases of raw materials and the sale of the corresponding finished goods.

This time lag is not the only complicating factor. It is unusual for companies to buy and sell in cash. Usually, their suppliers grant them extended payment periods, and they can in turn grant their customers extended payment periods. The money received during the day does not necessarily come from sales made on the same day.

As a result of customer credit,2 supplier credit3 and the time it takes to manufacture and sell products or services, the operating cycle of each and every company spans a certain period, leading to timing differences between operating outflows and the corresponding operating inflows.

Each business has its own operating cycle of a certain length that, from a cash flow standpoint, may lead to positive or negative cash flows at different times. Operating outflows and inflows from different cycles are analysed by period, e.g. by month or by year. The balance of these flows is called operating cash flow. Operating cash flow reflects the cash flows generated by operations during a given period.

In concrete terms, operating cash flow represents the cash flow generated by the company’s operations. Returning to our initial example of an individual looking at his bank statement, it represents the difference between the receipts and normal outgoings, such as food, electricity and rent.

Naturally, unless there is a major timing difference caused by some unusual circumstances (start-up period of a business, very strong growth, very strong seasonal fluctuations), the balance of operating receipts and payments should be positive.

Readers with accounting knowledge will note that operating cash flow is independent of any accounting policies, which makes sense since it relates only to cash flows. More specifically:

- neither the company’s depreciation and provisioning policy,

- nor its inventory valuation method,

- nor the techniques used to defer costs over several periods have any impact on the figure.

However, the concept is affected by decisions about how to classify payments between investment and operating outlays, as we will now examine more closely.

2/ INVESTMENT AND OPERATING OUTFLOWS

Let’s return to the example of our greengrocer, who now decides to add frozen food to his business.

The operating cycle will no longer be the same. The greengrocer may, for instance, begin receiving deliveries once a week only and will therefore have to run much larger inventories. Admittedly, the impact of the longer operating cycle due to much larger inventories may be offset by larger credit from his suppliers. The key point here is to recognise that the operating cycle will change.

The operating cycle is different for each business and, generally speaking, the more sophisticated the end product, the longer the operating cycle.

But most importantly, before he can start up this new activity, our greengrocer needs to invest in a chest freezer.

What difference is there between this investment and operating outlays?

The outlay on the chest freezer seems to be a prerequisite. It forms the basis for a new activity, the success of which is unknown. It appears to carry higher risks and will be beneficial only if overall operating cash flow generated by the greengrocer increases. Lastly, investments are carried out from a long-term perspective and have a longer life than that of the operating cycle. Indeed, they last for several operating cycles, even if they do not last forever given the fast pace of technological progress.

This justifies the distinction, from a cash flow perspective, between operating and investment outflows.

Normal outflows, from an individual’s perspective, differ from an investment outflow in that they afford enjoyment, whereas investment represents abstinence. As we will see, this type of decision represents one of the vital underpinnings of finance. Only the very puritanically minded would take more pleasure from buying a microwave than from spending the same amount of money at a restaurant! Only one of these choices can be an investment and the other an ordinary outflow. So, what purpose do investments serve? Investment is worthwhile only if the decision to forego normal spending, which gives instant pleasure, will subsequently lead to greater gratification.

This is the definition of the return on investment (be it industrial or financial) from a cash flow standpoint. We will use this definition throughout this book.

The impact of investment outlays is spread over several operating cycles. Financially, capital expenditures are worthwhile only if inflows generated thanks to these expenditures exceed the outflows by an amount yielding at least the return on investment expected by the investor.

Note also that a company may sell some assets in which it has invested in the past. For instance, our greengrocer may decide after several years to trade in his freezer for a larger model. The proceeds would also be part of the investment cycle.

3/ FREE CASH FLOW

Before-tax free cash flow is defined as the difference between operating cash flow and capital expenditure net of fixed asset disposals.

As we shall see in Sections II and III of this book, free cash flow can be calculated before or after tax. It also forms the basis for the most important valuation technique. Operating cash flow is a concept that depends on how expenditure is classified between operating and investment outlays. Since this distinction is not always clear-cut, operating cash flow is not widely used in practice, with free cash flow being far more popular. If free cash flow turns negative, then additional financial resources will have to be raised to cover the company’s cash flow requirements.

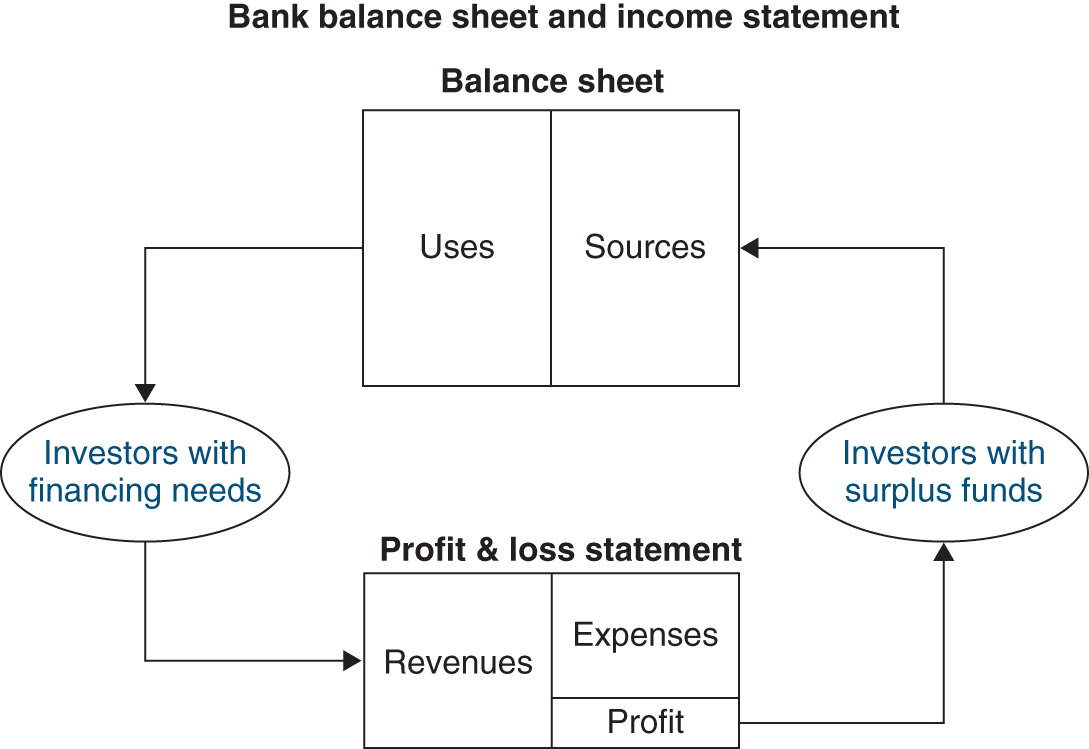

Section 2.3 FINANCIAL RESOURCES

The operating and investment cycles give rise to a timing difference in cash flows. Employees and suppliers have to be paid before customers settle up. Likewise, investments have to be completed before they generate any receipts. Naturally, this cash flow deficit needs to be filled. This is the role of financial resources.

The purpose of financial resources is simple: they must cover the shortfalls resulting from these timing differences by providing the company with sufficient funds to balance its cash flow.

These financial resources are provided by investors: shareholders, debtholders, lenders, etc. These financial resources are not provided with “no strings attached”. In return for providing the funds, investors expect to be subsequently rewarded by receiving dividends or interest payments, registering capital gains, etc. This can happen only if the operating and investment cycles generate positive cash flows.

To the extent that the financial investors have made the investment and operating activities possible, they expect to receive, in various different forms, their fair share of the surplus cash flows generated by these cycles.

At its most basic, the principle would be to finance these treasury shortfalls solely using capital that incurs the risk of the business. Such capital is known as shareholders’ equity. This type of financial resource forms the cornerstone of the entire financial system. Its importance is such that shareholders providing it are granted decision-making powers and control over the business in various different ways. From a cash flow standpoint, the equity cycle comprises inflows from capital increases and outflows in the form of dividend payments to the shareholders.

Like individuals, a business may decide to ask lenders rather than shareholders to help it cover a cash flow shortage. Bankers will lend funds only after they have carefully analysed the company’s financial health. They want to be nearly certain of being repaid and do not want exposure to the company’s business risk. These cash flow shortages may be short term or long term, but lenders do not want to take on business risk. The capital they provide represents the company’s debt capital.

The debt cycle is the following: the business arranges borrowings in return for a commitment to repay the capital and make interest payments regardless of trends in its operating and investment cycles. These undertakings represent firm commitments, ensuring that the lender is certain of recovering its funds provided that the commitments are met. Debt can finance:

- the investment cycle, with the increase in future net receipts set to cover capital repayments and interest payments on borrowings; and

- the operating cycle, with credit making it possible to bring forward certain inflows or to defer certain outflows.

From a cash flow standpoint, the life of a business comprises an operating and an investment cycle, leading to a positive or negative free cash flow. If free cash flow is negative, then the financing cycle covers the funding shortfall. But free cash flow cannot be forever negative: sooner or later investors must get a return and/or get repaid, and they can only get a return and/or get repaid by a positive free cash flow.

The risk incurred by the lender is that this commitment will not be met. Theoretically speaking, debt may be regarded as an advance on future cash flows generated by the investments made and guaranteed by the company’s shareholders’ equity.

Although a business needs to raise funds to finance investments, it may also find, at a given point in time, that it has a cash surplus, i.e. the funds available exceed cash requirements.

These investments are generally realised with a view to ensuring the possibility of a very quick exit without any risk of losses.

Although at first sight short-term financial investments (marketable securities) may be regarded as investments since they generate a rate of return, we advise readers to consider them instead as the opposite of debt. As we will see, company treasurers often have to raise additional debt even if at the same time the company holds short-term investments without speculating in any way.

Debt and short-term financial investments or marketable securities should not be considered independently of each other, but as inextricably linked. We suggest that readers reason in terms of debt net of short-term financial investments and financial expense net of financial income.

Putting all the individual pieces together, we arrive at the following simplified cash flow statement, with the balance reflecting the net decrease in the company’s debt during a given period:

SIMPLIFIED CASH FLOW STATEMENT

| n – 2 | n – 1 | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating receipts − Operating payments | |||

| = Operating cash flow | |||

| − Capital expenditure + Fixed asset disposals | |||

| = Free cash flow before tax | |||

| − Financial expense net of financial income − Corporate income tax + Proceeds from share issue − Dividends paid | |||

| = Net decrease in debt | |||

| With: Repayments of borrowings − New bank and other borrowings + Change in marketable securities + Change in cash and cash equivalents | |||

| = Net decrease in debt |

This short chapter is seminal and the reader who is discovering the notions it contains for the first time should not hesitate to read it twice in order to grasp them fully.

SUMMARY

QUESTIONS

EXERCISES

ANSWERS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTES

Chapter 3. EARNINGS

Time to put our accounting hat on!

Following our analysis of company cash flows, it is time to consider the issue of how a company creates wealth. In this chapter, we are going to study the income statement to show how the various cycles of a company create wealth.

Section 3.1 ADDITIONS TO WEALTH AND DEDUCTIONS FROM WEALTH

What would your spontaneous answer be to the following questions?

- Does purchasing an apartment make you richer or poorer?

- Would your answer change if you were to buy the apartment on credit?

There can be no doubt as to the correct answer. Provided that you pay the market price for the apartment, your wealth is not affected whether or not you buy it on credit. Our experience as teachers has shown us that students often confuse cash and wealth.

Consequently, we advise readers to train their minds by analysing the impact of all transactions in terms of cash flows and wealth impacts.

For instance, when you buy an apartment, you become neither richer nor poorer, but your cash decreases. Arranging a loan makes you no richer or poorer than you were before (you owe the money), but your cash has increased. If a fire destroys your house and it was not insured, you are worse off, but your cash position has not changed, since you have not spent any money.

Raising debt is tantamount to increasing your financial resources and commitments at the same time. As a result, it has no impact on your net worth. Buying an apartment for cash results in a change in the nature of your assets (reduction in cash, increase in real estate assets), without any change in net worth. The possible examples are endless. Spending money does not necessarily make you poorer. Likewise, receiving money does not necessarily make you richer.

The job of listing all the items that positively or negatively affect a company’s wealth is performed by the income statement,1 which shows all the additions to wealth (revenues) and all the deductions from wealth (charges or expenses or costs). The fundamental aim of all businesses is to increase wealth. Additions to wealth cannot be achieved without some deductions from wealth. In sum, earnings represent the difference between additions to and deductions from wealth.

Since the rationale behind the income statement is not the same as for a cash flow statement, some cash flows do not appear on the income statement (those that neither generate nor destroy wealth). Likewise, some revenues and costs are not shown on the cash flow statement (because they have no impact on the company’s cash position).

1/ EARNINGS AND THE OPERATING CYCLE

The operating cycle forms the basis of the company’s wealth. It consists of both:

- additions to wealth (products and services sold, i.e. products and services whose worth is recognised in the market); and

- deductions from wealth (consumption of raw materials or goods for resale, use of labour, use of external services such as transportation, taxes and other duties).

The very essence of a business is to increase wealth by means of its operating cycle.

It may be described as gross insofar as it covers just the operating cycle and is calculated before non-cash expenses such as depreciation and amortisation, and before interest and taxes.

2/ EARNINGS AND THE INVESTING CYCLE

(a) Principles

Investing activities do not appear directly on the income statement. In a wealth-oriented approach, an investment represents a use of funds that retains some value.

That said, the value of investments may change over time:

(b) Accounting for a decrease in the value of fixed assets

The decrease in value of a fixed asset due to its use by the company is accounted for by means of depreciation and amortisation.3

Impairment losses or write-downs on fixed assets recognise the loss in value of an asset not related to its day-to-day use, i.e. the unforeseen diminution in the value of:

- an intangible asset (goodwill, patents, etc.);

- a tangible asset (property, plant and equipment);

- an investment in a subsidiary.

3/ THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN OPERATING COSTS AND FIXED ASSETS

Although we are easily able to define investment from a cash flow perspective, we recognise that our approach goes against the grain of the traditional presentation of these matters, especially as far as those familiar with accounting are concerned:

- Whatever is consumed as part of the operating cycle to create something new belongs to the operating cycle. Without wishing to philosophise, we note that the act of creation always entails some form of destruction.

- Whatever is used without being destroyed directly, thus retaining its value, belongs to the investment cycle. This represents an immutable asset or, in accounting terms, a fixed asset (a “non-current asset” in IFRS terminology).

For instance, to make bread, a baker uses flour, salt, yeast and water, all of which form part of the end product. The process also entails labour, which has a value only insofar as it transforms the raw material into the end product. At the same time, the baker also needs a bread oven, which is absolutely essential for the production process, but is not destroyed by it. Though this oven may experience wear and tear, it will be used many times over.

This is the major distinction that can be drawn between operating costs and fixed assets. It may look deceptively straightforward, but in practice is no clearer than the distinction between investment and operating outlays. For instance, does an advertising campaign represent a charge linked solely to one period with no impact on any other? Or does it represent the creation of an asset (a brand)?

4/ THE COMPANY’S OPERATING PROFIT

From EBITDA, which is linked to the operating cycle, we deduct non-cash costs, which comprise depreciation and amortisation and impairment losses or write-downs on fixed assets.

This gives us operating income or operating profit or EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes), which reflects the increase in wealth generated by the company’s industrial and commercial activities.

The term “operating” contrasts with the term “financial”, reflecting the distinction between the real world and the realms of finance. Indeed, operating income is the product of the company’s industrial and commercial activities before its financing operations are taken into account. Operating profit or EBIT may also be called operating income, trading profit or operating result.

5/ EARNINGS AND THE FINANCING CYCLE

(a) Debt capital

Repayments of borrowings do not constitute costs but, as their name suggests, merely repayments.

Just as common sense tells us that securing a loan does not increase wealth, neither does repaying a borrowing represent a charge.

We emphasise this point because our experience tells us that many mistakes are made in this area.

Conversely, we should note that the interest payments made on borrowings lead to a decrease in the wealth of the company and thus represent an expense for the company. As a result, they are shown on the income statement.

Similarly, when a company invests cash in financial products (money market funds, interest-bearing accounts), the interest received is recognised as financial income. The difference between financial income and financial expense is called net financial expense/(income).

The difference between operating profit and net financial expense is called profit before tax and non-recurring items.4

(b) Shareholders’ equity

From a cash flow standpoint, shareholders’ equity is formed through issuance of shares minus outflows in the form of dividends or share buy-backs. These cash inflows give rise to ownership rights over the company. The income statement measures the creation of wealth by the company; it therefore naturally ends with the net earnings (also called net profit). Whether the net earnings are paid in dividends or not is a simple choice of cash position made by the shareholder.

If we take a step back, we see that net earnings and financial interest are based on the same principle of distributing the wealth created by the company. Likewise, income tax represents earnings paid to the state in spite of the fact that it does not contribute any funds to the company.

6/ RECURRENT AND NON-RECURRENT ITEMS: EXTRAORDINARY AND EXCEPTIONAL ITEMS, DISCONTINUED OPERATIONS

We have now considered all the operations of a business that may be allocated to the operating, investing and financing cycles of a company. That said, it is not hard to imagine the difficulties involved in classifying the financial consequences of certain extraordinary events, such as losses incurred as a result of earthquakes, other natural disasters or the expropriation of assets by a government.

They are not expected to occur frequently or regularly and are beyond the control of a company’s management – hence, the idea of creating a separate catch-all category for precisely such extraordinary items.

We will see in Chapter 9 that the distinction between non-recurring and recurring items is a difficult and subjective distinction, all the more so as accounting standards do little to help us.

Among the many different types of exceptional events, we will briefly focus on asset disposals. Investing forms an integral part of the industrial and commercial activities of businesses. But the best-laid plans may fail, while others may lead down a strategic impasse.

Put another way, disinvesting is also a key part of an entrepreneur’s activities. It generates exceptional “asset disposal” inflows on the cash flow statement and capital gains and losses on the income statement, which may appear under exceptional items or not. It is for the analyst to decide whether these gains and losses are recurring, and thus part of the operations; or not, and then constitute non-recurring items. More generally, some non-recurring items have a cash impact, some have none (goodwill depreciation, for example).

By definition, it is easier to analyse and forecast profit before tax and non-recurrent items than net income or net profit, which is calculated after the impact of non-recurrent items and tax.

7/ NET INCOME

Net income measures the creation or destruction of wealth during the fiscal year. Net income is a wealth indicator, not a cash indicator. It incorporates wealth-destructive items like depreciation, which are non-cash items, and most of the time it does not show increases in value, which are only recorded when they are realised through asset sales.

Section 3.2 DIFFERENT INCOME STATEMENT FORMATS

Two main formats of income statement are frequently used, which differ in the way they present revenues and expenses related to the operating and investment cycles. They may be presented either:

- by function,5 i.e. according to the way revenues and costs are used in the operating and investing cycle. This shows the cost of goods sold, selling and marketing costs, research and development costs and general and administrative costs; or

- by nature,6 i.e. by type of expenditure or revenue, which shows the change in inventories of finished goods and in work in progress (closing minus opening inventory), purchases of and changes in inventories of goods for resale and raw materials (closing minus opening inventory), other external costs, personnel expenses, taxes and other duties, depreciation and amortisation.

| Presentation | China | France | Germany | India | Italy | Japan | Morocco | Russia | Switzerland | UK | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By nature | 0% | 23% | 30% | 100% | 66% | 10% | 100% | 21% | 27% | 10% | 0% | |

| By function | 92% | 53% | 67% | 0% | 27% | 90% | 0% | 75% | 66% | 90% | 60% | |

| Other | 8% | 23% | 3% | 0% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 4% | 7% | 0% | 40% |

Source: 2020 annual reports from the top 30 listed non-financial groups in each country

The by-nature presentation predominates to a great extent in Italy, India and Morocco. In the US, the by-function presentation is largely predominant.7

Whereas in the past, France, Germany and Switzerland tended to use systematically the by-nature or by-function format, the current situation is less clear-cut. Moreover, a new presentation is making some headway; it is mainly a by-function format but depreciation and amortisation are not included in the cost of goods sold, in selling and marketing costs or research and development costs, but are isolated on a separate line.

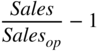

The two different income statement formats can be summarised by the following diagram:

1/ THE BY-FUNCTION INCOME STATEMENT FORMAT

This presentation is based on a management accounting approach, in which costs are allocated to the main corporate functions:

| Function | Corresponding cost |

|---|---|

| Production | Cost of sales, or cost of goods sold |

| Commercial | Selling and marketing costs |

| Research and development | Research and development costs |

| Administration | General and administrative costs |